Originality is not necessarily a product of spontaneity, though it may be. A person with an invention may be exceptionally good at what she does, may be especially insightful or may just get lucky. Usually, though, certain people seem to have a talent for originality, either in a particular field or in several. An original contribution to any field expands the field and gives others a wider base of information from which to draw for their own creative endeavors.

Real

True Narratives

Books by and about Igor Stravinsky:

- Igor Stravinsky, An Autobiography (1936)

- Stephen Walsh, Stravinsky: A Creative Spring: Russia and France: 1882-1934 (University of California Press, 1999).

- Stephen Walsh, Stravinsky: The Second Exile: France and America, 1934-1971 (Knopf, 2006).

- Gretchen Horlacher, Building Blocks: Reputation and Continuity in the Music of Stravinsky (Yale University Press, 2001).

- Charles M. Joseph, Stravinsky Inside Out (Yale University Press, 2001).

- Jonathan Cross, The Cambridge Companion to Stravinsky (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Eric Walter White, Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works (University of California Press, 2nd ed., 1980).

Other works:

- Mary Gabriel, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art (Little, Brown and Company, 2017): about five important women in the visual arts

- David Sedaris, Calypso (Little, Brown and Company, 2018): “I have come to the conclusion that David Sedaris is not just some geeky Samuel Pepys, as I had assumed all these years. True, he may shed a revelatory light on the more extreme facets of our societal spectrum through his bizarre and pithy prism. Yes, his worldview — a fascinating hybrid of the curious, cranky and kooky — does indeed hold a mirror up to nature and show us as others see us. But make no mistake: He is not the Fool, he is Lear.”

- Mark Dery, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey (Little, Brown & Company, 2018): “A New Biography Takes on Edward Gorey, a Stubborn Enigma and Master of the Comic Macabre”

- Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (Pantheon, 2003): “Satrapi's book combines political history and memoir, portraying a country's 20th-century upheavals through the story of one family. Her protagonist is Marji, a tough, sassy little Iranian girl, bent on prying from her evasive elders if not truth, at least a credible explanation of the travails they are living through.”

- Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis: The Story of a Return (Pantheon, 2004).

- Holly George-Warren, Janis: Her Life and Music (Simon & Schuster, 2019): “This was in an era of pretty soprano voices like Joan Baez’s. Joplin was like the girl in the fairy tale who, every time she opens her mouth, out hops a toad.”

- Eleanor Fitzsimons, The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit: Victorian Iconoclast, Children’s Author and Creator of “The Railway Children” (Abrams, 2019): “She was like a steampunk perpetual motion machine, popping out distinctive creative work and dynamic social plans on a conveyor belt that never stopped but sometimes had a hitch or two.”

- Leandra Ruth Zarnow, Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug (Harvard University Press, 2019): “When President Gerald Ford was in hot water for his pardon of Richard Nixon, he agreed to testify before a congressional committee as long as there was a time limit ‘and no questions from Bella Abzug.’”

- Francesca Wade, Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars (Tim Duggan, 2020): “Imagine five pioneering feminist scholars and writers assembled into one enchanting group portrait: the American poet Hilda Doolittle (known as H.D.), the novelist Dorothy L. Sayers, the classicist Jane Ellen Harrison, the medievalist Eileen Power and Virginia Woolf, whose career changed so much for women in literature and public life.”

- Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (New Directions, 2016): “. . . a highly original book of essays and observations . . .”

- Allen Ginsburg, The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats (Grove Press, 2017): “. . . Ginsberg asked his students to forget their preconceptions of what a poem or a story should be, and look instead for the ‘interior form’ they glimpsed beyond ‘the superficial level of mind’ of what they knew.”

- Ruth Brandon, Spellbound by Marcel: Duchamp, Love, and Art (Pegasus Books, 2022), is “a group biography of sorts, which charts, in sometimes gratuitous detail, the triangulated love affair between Duchamp, Wood and Roché, and the others who crossed their paths and their beds.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Adam Grant, Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World (Viking, 2016): “ . . . the world’s most original thinkers expose themselves to influences far outside their official arena of expertise.”

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Hideo Yokoyama, Six Four: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2017): “'Was it possible that, in that silence, all worlds were connected?' This strange question, which turns out to be the key sentence in Hideo Yokoyama’s superb 'Six Four,' sounds like something from a science-fiction novel, a lonely astronaut’s meditation in deep space. But 'Six Four' is a crime novel . . . . this novel is a real, out-of-the-blue original. I’ve never read anything like it.”

- Sam Lipsyte, No One Left to Come Looking for You: A Novel (Simon & Schuster, 2022), “is no one’s idea of a formulaic book, unless the formula is to write one original and unpretentious and funny sentence after another.”

- Selby Wynn Schwartz, After Sappho: A Novel (Liveright, 2023), is “an informal history of the emergence of modernism, told through interconnected anecdotes about real-life women artists, writers, intellectuals, actors, translators, dancers and feminist troublemakers in Europe at the turn of the 20th century.”

- Kelly Link, The Book of Love: A Novel (Penguin Random House, 2024): “Seven years in the making, ‘The Book of Love’ — long, but never boring — enacts a transformation of a different kind: It is our world that must expand to accommodate it, we who must evolve our understanding of what a fantasy novel can be.”

Poetry

From the shadow side:

- John Keats, Sonnet: “If By Dull Rhymes Our English Must Be Chained”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Glenn Gould was perhaps the patron saint of unconventionality among classical pianists. He took more liberties with the scores than perhaps any other musician. He often hummed audibly as he played. “Even to his most passionate admirers, the phenomenally gifted if wildly unconventional pianist Glenn Gould was a tangle of personal tics and complexes.” He was weird. “His April 1962 performance of Brahms’ first piano concerto, with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein conducting, gave rise to an extraordinary situation in which Mr. Bernstein disagreed with Gould’s interpretation so vehemently that he felt it necessary to warn the audience beforehand.” The title of a biography describes Gould as “Wondrous Strange”. Here is a link to his releases.

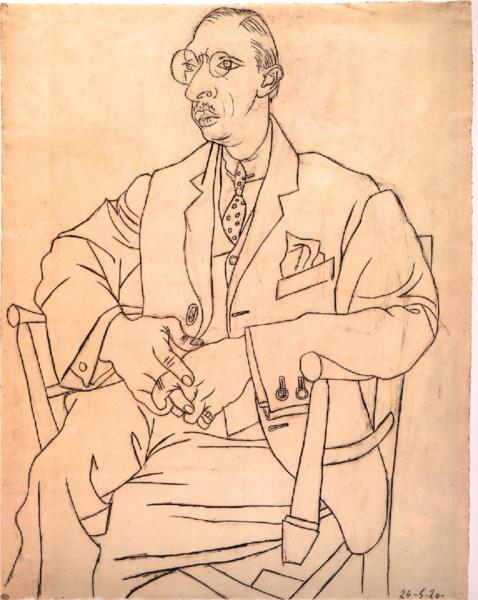

Many great composers defied convention. For example, Mahler was thought to be a minor composer until fifty years after his death, when musicologists and the general public began to understand his work. Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, (Le Sacre du Printemps) (1913) (approx. 33-40’) with its scandalously primeval rhythms and force, was so unconventional that it incited a riot at its premier performance in 1913. “The story itself is concerned with a prehistoric society in pagan Russia, which every year must sacrifice a virgin to ensure that the gods will be pleased in order to continue the group's survival. Ultimately, one such girl is chosen, and as the other performers visually align themselves with the earth, she is forced by the elders of the tribe to dance herself to death.” Stravinsky took music into the realm of the subconscious in a way no one had done before, and in so doing shocked the conscience of professional musicians and musicologists, and the public at large. “. . . Stravinsky explained that he did not write music for the sake of experimenting or promoting a radical change in the existing social order. Rather, he considered himself ‘the vessel through which Le Sacre passed’ . . . This detachment from intention created authenticity and liberated The Rite from the conventions that domesticated music . . . (producing) a phenomenon in its purest essence, a chaotic spirit that surpassed the composer’s immediate skill and forced a violent encounter of sound upon the audience.” Books by and about Stravinsky include an autobiography, “Memories and Commentaries” and biographies by Eric Walter White, Stephen Walsh, and Jonathan Cross. A documentary film has provided an analysis of the work. Stravinsky can justly be called the god of musical unconventionality. Top recorded performances of the orchestral version of The Rite of Spring are by Bernstein & New York Philharmonic in 1958, Markevitch & Philharmonia Orchestra in 1959, Stravinsky & Columbia Symphony Orchestra in 1960, Boulez & Cleveland Orchestra in 1969, Tilson Thomas & Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1972, Chailly & Cleveland Orchestra in 1987, Zander & Boston Philharmonic Orchestra in 1990 ***, Gergiev & Kirov Orchestra in 2001, Litton & Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra in 2009, Roth & Les Siècles in 2016, Jurowski & London Philharmonic Orchestra in 2022, and Mäkelä & Orchestre de Paris in 2023.

Other Stravinsky works include:

- The Rite of Spring (ballet) (1913) (approx. 30-42’): links are to performances at Mariinsky Theatre, and Joffrey Ballet.

- Petrushka: orchestral (1911) (approx. 34-40’) and ballet (1911) (approx. 40’) versions

- The Song of the Nightingale: tone poem (1917) (approx. 22’); ballet (1917) (approx. 26’); and opera (1914) (approx. 48’) versions

- The Soldier’s Tale: alternate staging (1918) (approx. 67’)

- Pulcinella: orchestral suite (1920) (approx. 39’) and ballet (1919) (approx. 42’)

- Octet for wind instruments (1923, rev. 1952) (approx. 16’)

- Oedipus Rex: (opera/oratorio) (1927) (approx. 52-58’)

- Apollon Musagéte: orchestral version (1928) (approx. 32-35’); ballet (approx. 29’)

- Dumbarton Oaks concerto in E-flat Major (1938) (approx. 15-16’)

- Symphony in C major (1940) (approx. 27-30’)

- Symphony of Psalms (1930, rev. 1948) (approx. 21-22’)

- Symphony in Three Movements (1945) (approx. 22-23’)

- Canticum Sacrum (1955) (approx. 16’)

- Agon (1957) (approx. 25’)

Giacinto Scelsi composed several suites for solo piano. This music “is delicious, disturbing, peaceful, stormy, and a host of other intermediate states of emotive bliss and uproar, but it is delightfully beyond the grasp of all the binary-seekers in search of the glib appellation.”

- Suite No. 8, “Bot-Ba” (1952) (approx. 26-30’)

- Suite No. 9, “Ttai” (1953) (approx 34-37’)

- Suite No. 10, “Ka” (1954) (approx. 20-23’)

- Suite No. 11 (1956) (approx. 39’)

Béla Bartók, Piano Concerto No. 1, Sz 83, BB 91 (1926) (approx. 25’): “The apotheosis of the cluster, of dissonant counterpoint, edgy syncopation, of percussiveness is the First Piano Concerto . . .” Top performances on disc are by Anda & Fricsay in 1959, Pollini & Abbado in 1979, Kocsis & Iván Fisher in 1987, Schiff & Iván Fisher in 1996, Zimerman & Boulez in 2004, Bavouzet & Noseda in 2010, and Aimard & Salonen in 2023.

Works by other composers:

- Mozart Camargo Guarnieri, Piano Concerto No. 4 (1968) (approx. 25’): this concerto employs unconventional techniques, including a compositional technique called serialism, “unorthodox sonorities as the piano plays accompanied by a vibraphone” (James Melo, from notes for this album), and atonality.

- Iannis Xenakis: A l’Ile de Gorée (1986) (approx. 16’); Naama (1984) (approx. 16’); Khaoï (1976) (approx. 15’); Komboï (1981) (approx. 18’)

- Đuro Živković, Citadel of Love (2020) (approx. 29’): “Various instrumental effects, such as the overblown flute, or string sounds played sul ponticello, cymbal strikes, and incessant and irregular chordal repetitions on the piano and mallet instruments, all combine to form a truly unique soundscape.”

Albums:

- Bluiett Baritone Saxophone Group, “Live at the Knitting Factory” (1998) (68’)

- John Stowell & Dan Dean, “Rain Painting” (2021) (48’): “Our ears are treated to what great possibilities there can be when we leave our harmonic comfort zones.”

- Trouble Kaze, “June” (2021) (47’): “If one enters into June with preconceived notions about music, they will be challenged to think again. Recorded live in Lille, France in 2016, without audience feedback, and with no breaks between the tracks, it is an extraordinary accomplishment that requires multiple plays to really absorb its essence. The real appeal of this collection transcends the overall content; it is fascinating in the intricacies of detail within the episodic narratives and it is unlike anything else.”

- Curtis K. Hughes, “Tulpa” (2021) (59’): “A very diverse listen that embraces atypical harmony and a skill set that includes both forceful and soothing musicianship, there isn’t a moment to be found here that isn’t exhilarating.”

- Selwyn Birchwood, “Pick Your Poison” (2017) (54’) – blues, Selwyn-style: “His richly detailed, hard-hitting originals run the emotional gamut from the humorously personal My Whiskey Loves My Ex to the gospel-inflected Even The Saved Need Saving to the hard truths of the topical Corporate Drone and Police State to the existential choice of the title track.”

- Hélène Duret & Synestet, “Rôles” (2022) (45’): “Rôles is an imaginary story where the established rules are very precise and at the same time never respected – after all, is that not the beauty of a rule? A story where the characters swap roles, blend or change their intentions as they see fit, creating – in the moment and in improvisation – a unique and ephemeral alchemy. The roles are swapped totally freely and the unforeseen slips into the mix. This leads to exchanges between a volatile electric rock guitar, a drummer who is at times a colourist and sometimes the band leader, melodies to sing in which saxophone, clarinet and double bass merge into one.”

- Equally original, and fascinating, is Synestet’s first album, “Les Usures” (2019) (36’): “Synestet is a call to the senses, where the perception of music becomes a mix of colours, shapes and smells. Five improv crazy musicians, with their thirst for playfulness and desire for musical expression around original compositions. A liberated form of music, extolling the virtues of simplicity, inventiveness, whilst highlighting the improvisational talents of its creators”

- Jim McNeeley, Frankfurt Radio Big Band & Chris Potter, “Rituals” (2022) (69’): Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring inspired this album of “innovative, challenging music that gets into your psyche as much as it gets into your appetite for improvisation.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Tom Waits, "The Piano Has Been Drinking" (lyrics)

- David Bowie, "Rebel Rebel" (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Wassily Kandinsky, Transverse Line (1923)

Film and Stage

- The Triplets of Belleville (Les Triplets de Belleville): a “creepy, eccentric, eerie, flaky, freaky, funky, grotesque, inscrutable, kinky, kooky, magical, oddball, spooky, uncanny, uncouth and unearthly” animated feature filmthat “doesn’t seem to care” whether you like it or not

- Repo Man, “a film that isn’t made from ay known formula and doesn’t follow the rules”; “a sneakily rude, truly zany farce that treats its lunatic characters with a solemnity that perfectly matches the way in which they see themselves”

- Re-Animator, a high-tech science-fiction film “with as much originality as it as gore and that’s saying something”