- . . . let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream. [The Bible, Amos 5:24.]

When someone wakes in the morning, she feels a certain way, sees certain things, touches certain things, and so forth. That experience is that person’s Truth in that moment.

To know that Truth in another, and honor it, is the Truth force. Though the Truth force is the great creative force in the domain of the intellect, it also has roots in the emotions and in action, for we cannot appreciate another person’s Truth in only one domain. It must be felt and experienced, as well as thought.

Mohandas K. Gandhi is renowned for his non-violent resistance movement, which demonstrated the power of Truth over violence and other means of denying the humanity of a person or persons. This Truth is the inner Truth of humanity, the Truth of Being. People can tell when it is being honored and when it is being violated. If this simple Truth is ever universally honored, war, racial, ethnic, gender and other forms of discrimination, exploitation, and every act that dishonors anyone’s humanity all will end.

Real

True Narratives

The circumstances in which I was then placed, gave me a longing desire to be free. It kindled a fire of liberty within my breast which has never yet been quenched. This seemed to be a part of my nature; it was first revealed to me by the inevitable laws of nature's God. I could see that the All-wise Creator, had made man a free, moral, intelligent and accountable being; capable of knowing good and evil. And I believed then, as I believe now, that every man has a right to wages for his labor; a right to his own wife and children; a right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness; and a right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience. But here, in the light of these truths, I was a slave, a prisoner for life; I could possess nothing, nor acquire anything but what must belong to my keeper. No one can imagine my feelings in my reflecting moments, but he who has himself been a slave. Oh! I have often wept over my condition, while sauntering through the forest, to escape cruel punishment.

"No arm to protect me from tyrants aggression;

No parents to cheer me when laden with grief.

Man may picture the bands of the rocks and the rivers,

The hills and the valleys, the lakes and the ocean,

But the horrors of slavery, he never can trace."

The term slave to this day sounds with terror to my soul--a word too obnoxious to speak--a system too intolerable to be endured. I know this from long and sad experience. I now feel as if I had just been aroused from sleep, and, looking back with quickened perception at the state of torment from whence I fled. [Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, Written by Himself (1849), Chapter I.]

Ida B. Wells opposed racial injustice. A former slave, standing less than five feet tall, she “wrote about the victims of racist violence and also organized economic boycotts long before the tactic was popularized."

- Alfreda M. Duster, ed., Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells (University of Chicago Press, 1991).

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr., ed., Ida B. Wells: The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynching Crusader (Penguin Classics, 2014).

- Ida B. Wells: Social Activist and Reformer (Routledge, 2016).

- Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (Amistad, 2008).

- Miriam DeCosta-Willis, ed., The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells: An Intimate Portrait of the Activist as a Young Woman (Beacon Press, 1995).

- Mia Bay, To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells (Hill and Wang, 2009).

- Linda O. McMurray, To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Patricia A. Schechter, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930 (University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

- Walter Dean Myers, Ida B. Wells: Let the Truth Be Told (Amistad, 2008).

Mohandas Gandhi:

- Mohandas K. Gandhi, Gandhi: An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With the Truth (Beacon Press, 1993; Courier Dover Publications, 1983).

- Stanley Wolpert, Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mohatma Gandhi (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Biographies of Truth – penetrating deeply into the subject:

- Roger Ebert, Life Itself: A Memoir (Grand Central Publishing, 2011), chronicling the critic’s life and career.

- Max Hastings, Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011): "'Inferno' offers an account of the war that concentrates on the lived experience of the men and women who took part in it."

History is littered with denials of the Truth of our common humanity.

- A.J. Langguth, Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War (Simon & Schuster, 2010).

- Susan Bayly, Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Nicholas B. Dirks, The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain (Belknap Press, 2006).

- Mark Sanders, Complicities: The Intellectual and Apartheid (Duke University Press, 2002).

- Mark Holborn and Hilary Roberts, The Great War: A Photographic Narrative (Imperial War Museums/Alfred A. Knopf, 2013): “The images presented here are not illustrations for a narrative; they are the narrative.”

- Peter Englund, The Beauty and the Sorrow: An Intimate History of the First World War (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011): “It’s not so much a book about what happened . . . as ‘a book about what it was like.’ It’s about ‘feelings, impressions, experiences and moods.’ ‘The Beauty and the Sorrow’ threads together the wartime experiences of 20 more or less unremarkable men and women, on both sides of the war, from schoolgirls and botanists to mountain climbers, doctors, ambulance drivers and clerks.”

- Chloe Hooper, The Arsonist: A Mind on Fire (Seven Stories, 2020), “follows the case against Sokaluk, a 39-year-old former volunteer firefighter, from the arson investigation’s first frantic hours to the courtroom verdict” and recounts the quiet dignity of witnesses.

- Jo Ann Beard, Festival Days (Little, Brown and Company, 2021): “We can rely on Jo Ann Beard to miss nothing. She will gather the essential elements and arrange them before us with such precision that, without instructing us how to see, she grants us sight.”

- Elizabeth Alexander, The Trayvon Generation (Grand Central Publishing, 2022): “. . . a profound and lyrical meditation on race, class, justice and their intersections with art . . . ‘I call the young people who grew up in the past 25 years the Trayvon Generation,’ the ones who grew up hearing the words, ‘Two seconds, I can’t breathe, traffic stop, dashboard cam, 16 times.” She writes: 'These stories formed their worldview.' . . .”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Mohandas K. Gandhi, Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha) (Shocken Books, 1961).

- Mohandas K. Gandhi, Satyagraha in South Africa (Academic Reprints, 1954).

- Jesse van der Valk, Satyagraha: The Gandhian Faith in Non-Violence (Routledge, 2004).

- Dalai Lama, For the Benefit of All Beings: A Commentary On the Way of the Bodhisattva (Shambhala, 2009).

- Santideva, The Way of the Bodhisattva (Shambhala, 2008).

- Santideva, Bodhicaryavatara (Windhorse Publications, 2004).

- Pema Chodron, No Time to Lose: A Timely Guide to the Way of the Bodhisattva (Shambhala, 2005).

- Chokyi Dragpa, Uniting Wisdom and Compassion: Illuminating the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva (Wisdom Publications, 2004).

- Dilgo Khyentsie Rinpoche, The Heart of Compassion: The Thirty-Seven Verses on the Practice of a Bodhisattva (Shambhala, 2007).

- Dilgo Khyentsie Rinpoche, Enlightened Courage: An Explanation of Seven-Point Mind Training (Snow Lion Publications, 2006).

- Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, Meaningful to Behold: The Bodhisattva's Way of Life (Tharpa Publications, 2008).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

-

The Devil Came On Horseback: a former marine joins the African Union peacekeeping force and uses photographs of the horrors he sees as a tool for bringing peace and justice to the people being abused.

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

It is impossible to conceive of a human creature more wholly desolate and forlorn than Eliza, when she turned her footsteps from Uncle Tom's cabin. Her husband's suffering and dangers, and the danger of her child, all blended in her mind, with a confused and stunning sense of the risk she was running, in leaving the only home she had ever known, and cutting loose from the protection of a friend whom she loved and revered. Then there was the parting from every familiar object,--the place where she had grown up, the trees under which she had played, the groves where she had walked many an evening in happier days, by the side of her young husband,--everything, as it lay in the clear, frosty starlight, seemed to speak reproachfully to her, and ask her whither could she go from a home like that? [Harriett Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly (1852), Volume 1, Chapter 7, “The Mother’s Struggle”.]

Novels:

- Jan Chosen Bays, Jizo Bodhisattva: Guardian of Children, Travelers & Other Voyagers (Shambhala, 2003).

- Julie Otsuka, The Buddha in the Attic (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011): told in the collective first-person voice of young Japanese women shipbound for the United States as picture brides in the early twentieth century, this short novel “captur(es) not just images but sensations, not just surfaces but the essence of what lies within.”

- Peter Nadas, A Book of Memories: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux): a “novel of consciousness.”

- Clare Clark, Beautiful Lies: A Novel (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012): “A captivating tale of truth and memory,” this novel “is about the kaleidoscopic nature of reality,” asking “What is truth – and what is Maribel’s truth?”

- Louis Begley, Memories of a Marriage: A Novel (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2013), “while concerning itself with the search for truth in the most private spaces, also addresses the larger question of how anyone ever goes about finding the truth.”

- Alice Sebold, The Lovely Bones (Little Brown, 2002): the protagonist is a murdered fifteen-year-old girl telling of her life from heaven.

- Priya Parmar, Vanessa and Her Sister: A Novel (Ballantine Books, 2015): “ . . . Parmar gives truth and definition to the character of a woman whose nature was as elusive as her influence was profound. She has caught the phantom.”

- Victor LaValle, The Changeling: A Novel (Spiegel & Grau, 2017): “ . . . LaValle does more than his share of truth-telling, about the anxieties and ambivalences of modern parenting, the psychological value of the stories we tell ourselves and our children, and the rigors of survival in urban America.”

- Roxane Gay, An Untamed State: A Novel (Black Cat/Grove/Atlantic, 2014): “When Mireille finally does return to Haiti, much stronger and intent on avenging her own ‘death,’ her target is not her captors but her father. She wants to break him with the ‘whole, filthy truth of my kidnapping, even the parts I hadn’t told Michael.’ But her humanity overrides revenge: ‘When I looked into his face, all I saw was an old man who made a terrible, weak choice and had to live with it for what remained of his life. He did not deserve the truth of how I died.’”

- Lisa Halliday, Asymmetry: A Novel (Simon & Schuster, 2018): “ . . . a clever comedy of manners set in Manhattan as well as a slowly unspooling tragedy about an Iraqi-American family, which poses deep questions about free will, fate and freedom, the all-powerful accident of one’s birth and how life is alchemized into fiction.”

- Sarah Hall, Burntcoat: A Novel (Custom House, 2021): “In practice, Hall seems far less interested in the terrifying things human creatures might do to one another than in examining their fragility, dwarfed by some impersonal looming fate: exile, a cyst, a virus.”

- Kate Atkinson, Shrines of Gaiety: A Novel (Doubleday, 2022): “Atkinson vividly conjures the post-Great War London of a century ago, a vast stinking metropolis still teetering between the old world and the new. It’s also a place so bent on burying its mass trauma in a sort of collective, hectic hedonism that one character wonders whether they weren’t ‘following some instinctive compulsion to restock the human race. Like frogs.'”

- Sevgi Soysal, Dawn: A Novel (1975): “The ingenuity of ‘Dawn’ lies in its chorus of wounded, weary, angry voices from all corners of Turkish society.”

- Laurent Mauvignier, The Birthday Party: A Novel (Transit Books, 2023), “is a thriller with an intense focus on its characters’ interior worlds.”

- Jessica George, Maame: A Novel (St. Martin’s Press, 2023): “. . . dark moments commingle with light ones, exactly as they do in real life.”

Poetry

A curious boy asks an old soldier

Sitting in front of the grocery store,

"How did you lose your leg?"

And the old soldier is struck with silence,

Or his mind flies away

Because he cannot concentrate it on Gettysburg.

It comes back jocosely

And he says, "A bear bit it off."

And the boy wonders, while the old soldier

Dumbly, feebly lives over

The flashes of guns, the thunder of cannon,

The shrieks of the slain,

And himself lying on the ground,

And the hospital surgeons, the knives,

And the long days in bed.

But if he could describe it all

He would be an artist.

But if he were an artist there would be deeper wounds

Which he could not describe.

There is the silence of a great hatred,

And the silence of a great love,

And the silence of an embittered friendship.

There is the silence of a spiritual crisis,

Through which your soul, exquisitely tortured,

Comes with visions not to be uttered

Into a realm of higher life.

There is the silence of defeat.

There is the silence of those unjustly punished;

And the silence of the dying whose hand

Suddenly grips yours.

There is the silence between father and son,

When the father cannot explain his life,

Even though he be misunderstood for it.

There is the silence that comes between husband and wife.

There is the silence of those who have failed;

And the vast silence that covers

Broken nations and vanquished leaders.

There is the silence of Lincoln,

Thinking of the poverty of his youth.

And the silence of Napoleon

After Waterloo.

And the silence of Jeanne d'Arc

Saying amid the flames, "Blessed Jesus" --

Revealing in two words all sorrows, all hope.

And there is the silence of age,

Too full of wisdom for the tongue to utter it

In words intelligible to those who have not lived

The great range of life.

[from Edgar Lee Masters, “Silence”]

Brandon Leake is a young man who has written and recited poems that cut to the core of Truth in his life.

- About his sister;

- About his mother;

- About his father;

- About his newborn daughter.

Other poems:

- Maya Angelou, “A Brave and Startling Truth”

- Maya Angelou, “Woman Work”

Books of poems:

- Adam Zagajewski, True Life: Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023): “When Zagajewski was a child, his Polish family was expelled from his birthplace by the Kremlin of Putin’s predecessors. The poet died in March 2021, a couple of years after the publication of ‘True Life’ in Polish, and a year before the Russian invasion. His work, resembling Lviv in its multiple, interpenetrating layers of memory, remains an international model.”

From the dark side:

- Edgar Lee Masters, “The Circuit Judge”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Early Billie Holiday, 1933-1944: This iconic African-American jazz singer stands out for her distinctive voice, and her life story. “. . . the raw emotional pull of her music was the result of a desperately chaotic lifestyle that the singer seemed unable to control.” For her, “the 1930s was a time of emergence.” These early recordings tell her story before decline was obvious in her voice.

José James captured Billie Holiday’s spirit, albeit with a velvety baritone voice, on his album “Yesterday I Had the Blues: The Music of Billie Holiday” (2015) (50’).

VRï is a Welsh chamber-folk trio whose work reflects a quality of pathos in Welsh culture. “'The chapel tradition sits on Welsh culture like the Berlin Wall . . . And it's still there.' On one side of the wall, the old Celtic joys of fiddling, dancing and carousing, together with a trove of traditional songs and stories every bit as lavish as those of Scotland and Ireland; on the other side, dark chapels built like power stations, formerly vibrant and warm with song, but now increasingly empty and strewn across the land like the gravestones of a faith that seemed so unshakeable. It's a bittersweet divide.” Their albums, “Islais a Genir” (A Sung Whisper) (2022) (57’), and “Tŷ Ein Tadau” (Our Fathers’ House) (2018) (43’), reflect that dual quality of joy and sadness, cutting to the core of life. “When we think about how to defend a marginalised culture or minority language, we often think in terms of struggle. This is perfectly understandable, and a certain amount of struggle is often necessary: the struggle to be heard and to be accepted underpins a whole host of human rights movements, linguistic revivals and political causes. But there is a flipside to the difficult battles and hard-won gains, which is, to put it simply, joy.”

Poorly acted, Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master Singer of Nurenberg) (1867) (approx. 240-295’) (libretto) can come across as a four-plus-hour piece of insufferable nonsense, a vehicle for Wagner’s music (which is not the best in the operatic repertoire anyway). However, in this 2011 performance from Glyndebourne, Gerald Finley as Hans Sachs, and the entire cast, deliver a compelling interpretation that elevates this opera and by comparison transforms it into the greatest vehicle for the illustration of human values of all operas. The storyline begins with a typically Wagnerian premise: a man has decided that his daughter Eva is to be given in marriage to the master singer who wins a singing contest, as judged by the members of the local master singers’ guild. She may refuse to marry the victor but then she may not marry anyone. Her suitor and love interest, an at-first too-eager Walther von Stolzing first appears creeping around inside a church during a service trying to ask her whether she will “say the word” and become his wife. He is informed of the singing contest, and off we go. Stolzing has not been designated a master singer but he appears at a guild meeting to audition for that distinction. Master singer Beckmesser, who wishes to marry Eva, serves as the “marker” who will determine whether Stolzing is worthy of the title master singer. Of course, the audition – which Stolzing sings brilliantly – is deemed a failure, ending his hope of ever becoming a master singer. The story’s protagonist Hans Sachs – a master singer, poet, and cobbler by trade – is incensed at the injustice, and at the foil Beckmesser. Remember, though, this is opera, so there is no such thing as never. Stolzing appears at Eva’s home, and the two decide to elope. As they prepare to elope, Beckmesser appears with his lute and performs a pitiful love ballad while Sachs cobbles a shoe, each strike of his hammer mimicking a mark with Beckmesser’s chalk during Stolzing’s audition. The third act opens with a despondent Sachs and the revelation of a depiction of his deceased wife and children. Stolzing, who has slept the night at Sach’s home, awakes after having a dream which he then puts to poetry and music. Sachs devises a plan for Stolzing to perform his song at the Midsummer’s Day festival (that day, of course), where the community will adjudge him a master singer, and he will win Eva’s hand. Beckmesser makes a fool of himself with another pitiful song, and then Stolzing triumphs with his song. Here are links to performances of the complete opera: Prohaska, Lorenz & Müller (Furtwängler) in 1943; Schöffler, Suthaus & Scheppan (Abendroth) in 1943; Stewart, Kónya & Janowitz (Kubelik) in 1967; Weikl, Heppner & Studer (Sawallisch) in 1993; and (Jordan) in 2017. Below are some of the values illustrated in this opera:

- Truth: Having lost his young family, Sachs appreciates the pain of others. The story also reveals the Truth of Stolzing’s and Eva’s romantic love.

- Intuition: Great art is not a matter of simply following the rules of composition; it must speak to the heart.

- Honesty: Great art is also honest.

- Art and Beauty: to Wagner, as is obvious from lyrics in the final scene, this was a story about the art of music.

- Praxis, Tradition and Unconventionality: By balancing conventionality and unconventionality, great artists take art forward. No doubt Wagner saw himself as a living example of that.

- Transcendence: A line in the final act asks what is the difference between a beautiful song and a master song. It is the transcendent quality that takes art beyond its conventions.

- Passion and Amore: Stolzing’s and Eva’s romantic love for each other

- Suffering, as represented most directly by the untimely death of Sachs’ young family

- Empathy and Compassion: Through the loss of his family, the suffering of others has become exquisitely palpable to Sachs.

- Authenticity: though talented, Stolzing writes and sings from his heart, in stark contrast to the foil Beckmesser.

- Humility: Beckmesser presents its antithesis.

- Self-awareness: again, Beckmesser presents its antithesis.

- Mentoring: Sachs mentors Eva and Stolzing, and also his apprentice David, whom he promotes to journeyman near the end of the opera – OK, so he beats David with a. strap on occasion but this is nineteenth-century Wagnerian opera.

- Perseverance, Faith and Miracles: Though he has been told that he can never become a master singer, Stolzing writes and sings his song, with considerable help from Sachs. David the apprentice also perseveres, and triumphs.

- Wisdom: Stolzing represents this virtue most fully, in this opera.

- Triumph: The opera’s opening chords announce a theme of triumph, which also closes the opera.

The haunting inner voice of the Afghan Rubâb:

- Mohammad Omar, with his playlists;

- Rahul Sharma, Humayun Sakhi and company, “In the Footsteps of Babur”

- Homayoun Sakhi, here, here, and with his playlists;

- Rashim Kushnawaz, with his playlists.

Philippe Gaubert, flute sonatas “are mainly of a melodious, lyrical nature. The sometimes romantic, orchestral colouring is a challenge for the piano accompanist. Their style is clearly neo-romantic and impressionistic.”

- Flute Sonata No. 1 (1917) (approx. 15’)

- Flute Sonata No. 2 (1924) (approx. 16’)

- Flute Sonata No. 3 (1934) (approx. 13’)

Other works:

- Max Reger, Aus meinem Tagebuch (From My Diary), Op. 82 (1904-1912) (approx. 130’)

- Ezra Laderman, Interior Landscapes I (approx. 12’)

- Laderman, Interior Landscapes II (approx. 15’)

- Laderman, Partita for Solo Cello No. 2 (approx. 17’)

- Laderman, Partita for Violin (1990) (approx. 20’)

- Daron Hagen, Orson Rehearsed (2021) (approx. 62’) (quasi-libretto) “is the psychological, emotional, and spiritual journey taken by the American actor, polymath, and creator of Citizen Kane Orson Welles, as he finds himself on the threshold between life and death.”

- Eleanor Alberga, The Soul’s Expression, for Baritone and String Orchestra (2017) (approx. 13’): “A darkly pithy quotation from George Eliot’s Adam Bede links each poem and provides a foil to the rapture within ‘Blue Wings’ and hope in ’Roses’. Languor occupies Brontë’s ‘The Sun Has Set’, while unanswered questions on the mystery of the soul posed by Barrett Browning conclude a work marked by a romantic sensibility and richly variegated string textures.” The work features this poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

- Line Tjørnhøj, enTmenschT (2018) (approx. 59’) “intricately weaves together the stories of two ill-fated couples to delve into the mysterious nature of the true self. Against the backdrop of the early 20th century and the tumultuous devastation of two world wars, this haunting and virtuosic song cycle reveals unexpected and thought-provoking insights into the human condition.”

John Minnock sings jazz tunes, some of them apparently original, with a plaintive quality like no one else’s, evoking the Truth of a life as it is lived. When he accompanies Minnock on saxophone, David Liebman brings to mind the singer’s inner life, as on these albums:.

- “Right Around the Corner” (2018) (44’);

- “Herring Cove” (2020) (55’); and

- “Every Day Blues” (2016) (45’).

Albums:

- Various artists, “The Many Loves of Antonín Dvořák” (2021) (238’) offers: an insight into the composer’s internal life through a selection of his works.

- Hayes McMullen, “Everyday Seem Like Murder Here” (2017) (62’): in his late sixties, McMullen’s blues sound like a black sharecropper in the Mississippi delta of the 1960s.

- Linsey Alexander, “Live at Rosa’s” (2020) (52’): “The son of sharecroppers, Alexander picked up the guitar for the first time at age 12, influenced by Rosco Gordon, Chuck Berry and Elvis as well as blues, country and early rock-‘n’-roll. After toiling as a hotel porter and bicycle technician in Mississippi, he pawned his only guitar to pay for his bus ride north to hook up with a lady he’d met in Memphis.”

- Jesper Sivebaek, “Ta’ Mig Med” (2021) (41’) presents songs for classical guitar by Kim Larsen.

- James Beckwith, “SE10” (20210 (61’) evokes a slice of life in SE10, the postal zone where Beckwith lives.

- Benyamin Nuss & Billy Test, “Mia Brentano’s Summer House” (2022) (67’) presents images from a life.

- Sachal Vasandani & Romain Collin, “Still Life” (2022) (45’): “'I feel like this music is intense ... in a quiet way,' Vasandani said. 'The truth is we’re both calm and even-headed, but this is a tough time for all of us, and we put it into our music.'”

- Angeline Morrison, “The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs of Black British Experience” (2022) (51’): “The haunting opening track, Unknown African Boy (d.1830), was the first song Morrison wrote for the album. 'I learned that slave ships regularly passed by the Isles of Scilly and several were wrecked. A local newspaper article of the time listed some of the items washed up on shore: palm oil, elephant tusks, boxes of silver dollars and gold dust, and the body of an unknown ‘West African boy – estimated age around eight’. The boy is buried in St Martin’s churchyard, Isles of Scilly. I wrote this song from the perspective of his mother.'”

- Vijay Iyer & Wadada Leo Smith, “A Cosmic Rhythm With Each Stroke” (2016) (66’), is an album following a path set by Smith in the 1960s: “Smith’s performance aesthetic signaled the arrival of a confident and original voice. He could craft mournful melodic lines that suggested the folk music of his Mississippi Delta youth, before quickly steering into rough-sounding yet controlled smears of notes. Then, in the midst of an improvisation, he would allow stretches of silence to enter his phrasing. In contrast to New York’s consistently in-the-red style of free-jazz, Smith and other AACM figures also experimented with world music instrumentation and modernist chamber composition in between passages of fiery blast.”

- Alvin Youngblood Hart, “Big Mama’s Door” (1996) (49’) and “Territory” (1998) (47’): Hart sings realistic country blues on these albums.

- American Patchwork Quartet, “American Patchwork Quartet” (2024) (54’): “Mirroring America’s cultural mosaic, APQ stitches together a story that’s both intricate and resilient. The fabric of their music is genuine—it neither feigns tolerance nor presents an overly-embellished image of unity. Instead, each carefully chosen piece dives deep into America’s patchwork soul and shares the joys, sorrows, and unwavering hope of a nation crafted by shared dreams and diverse histories.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Paul Simon, “René and Georgette Magritte with Their Dog After the War” (lyrics)

- Blaise Siwula, Nicolas Letman-Burtinovic & Jon Panikkar, “Truth”

Visual Arts

- Willem de Koonig, Woman IV (1953)

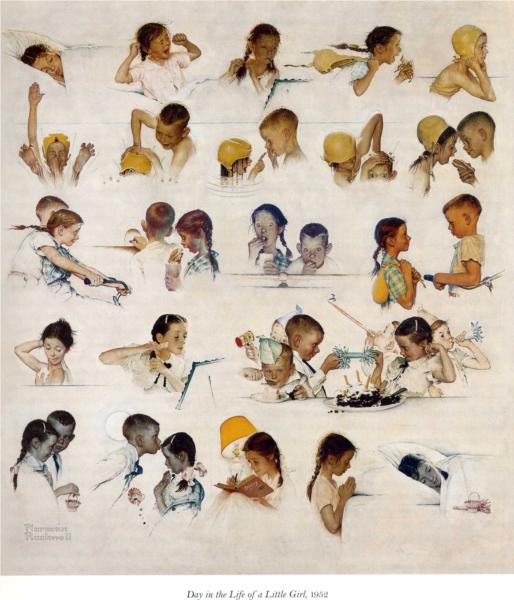

- Norman Rockwell, Faces of Boy

- Isaac Levitan, Portrait of Nikolay Panafidin (1891)

- Vincent van Gogh, Landscape with Couple Walking and Crescent Moon (1890)

- Paul Cezanne, Self-Portrait (1875)

- Ivan Kramskoy, Head of an Old Ukranian Peasant (1871)

- Nicolas Poussin, Self-Portrait (1650)

- Rembrandt van Rijn, Study of an Old Man in Profile (1630)

Film and Stage

- The final scene in "Witness" illustrates the power of Truth. An Amish child has witnessed a murder in which law enforcement officials are complicit. When the corrupt officials are about to harm the child, the peaceful men and women of the community bear witness to their choice. Circumstances conspire to make Truth more powerful than evil.

- Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles: presenting three days in the life of a “middle-class widow-and-mother who supports herself and her teenage son by prostitution each afternoon, in her depressingly tidy apartment”.