Evil is whatever denigrates human worth, seen as broadly as we can.

- When they were in the field Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him. [The Bible, Genesis 4:8.]

- We will be greatly misled if we feel that the problem will work itself out. Structures of evil do not crumble by passive waiting. If history teaches anything, it is that evil is recalcitrant and determined, and never voluntarily relinquishes its hold short of an almost fanatical resistance. Evil must be attacked by a counteracting persistence, by the day-to-day assault of the battering rams of justice. [Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community (1967), Chapter IV, “The Dilemma of Negro Americans”.]

Justice is honoring the worth and dignity of all persons; evil is denigrating, denying, diminishing or destroying it.

This is best seen from the core of Being outward. Intention is the essence of evil, whereas an action that is merely harmful is not generally seen that way; however, repeated harmful acts are less likely to be overlooked than a single honest mistake.

When we separate global “values” such as evil into their component parts (emotional feeling, thinking, and acting/doing), we arrive at ideas, conceptions and definitions that depart from the usual ways of thinking about human values. Though that may put some people off, or cause them to lose interest in this work, departure from norms is a main purpose and virtue of this work: much of our thinking about human values is muddled. That is why some new ideas and definitions are necessary.

In the Human Faith model, evil is anything that denies or denigrates human worth, and/or diminishes or blocks dignity. The denial/denigration may be intentional (moral evil defined in its narrowest sense) or unintentional (broadly defined evil). Because the model’s core commitment is to honor the intrinsic worth of all people, the idea of evil implies an avoidance of judgmentalism, or at least a reluctance to judge. That makes the idea of evil challenging. In the Human Faith model, evil includes a broad concept, as per the description of evil found in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

The broad concept picks out any bad state of affairs, wrongful action, or character flaw. The suffering of a toothache is evil in the broad sense as is a harmless lie. Evil in the broad sense has been divided into two categories: natural evil and moral evil. Natural evils are bad states of affairs which do not result from the intentions or negligence of moral agents. Hurricanes and toothaches are examples of natural evils. By contrast, moral evils do result from the intentions or negligence of moral agents. Murder and lying are examples of moral evils.

This distinction is essential, because in the Human Faith model, we break down global “values” such as evil analytically, considering them in each of the three ethical domains of emotional feeling, thinking and doing/acting. Many people may not recognize irrationality as an evil but in the Human Faith model, it is. Superficially, irrationality may not seem to be motivated by ill intent but a deep investigation into its roots in any individual at any time probably would yield the identification of something untoward, such as an insufficient commitment to reason or an excessive focus on self-gratification. Whether it did or did not do so, irrationality is profoundly undesirable in the domain of thinking, and therefore must be included in a broad definition of evil.

Of course, evil also includes a narrow concept of evil, which “picks out only the most morally despicable sorts of actions, characters, events, etc.” Such people are thought to be evil in relation to other people. Historical figures who are commonly thought to be evil include Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Idi Amin, Nero, Mao Zedong, and Genghis Khan. Each of these men exhibited evil on an epic scale, murdering, persecuting and oppressing large numbers of people.

Real

True Narratives

Why stands she near the auction stand? / That girl so young and fair; / What brings her to this dismal place? / Why stands she weeping there?

Why does she raise that bitter cry? / Why hangs her head with shame, / As now the auctioneer's rough voice / So rudely calls her name!

But see! she grasps a manly hand, / And in a voice so low, / As scarcely to be heard, she says, / "My brother, must I go?"

A moment's pause: then, midst a wail / Of agonizing woe, / His answer falls upon the ear.-- / "Yes, sister, you must go!"

No longer can my arm defend, / No longer can I save / My sister from the horrid fate / That waits her as a SLAVE!

Blush, Christian, blush! for e'en the dark / Untutored heathen see / Thy inconsistency, and lo! / They scorn thy God, and thee!

[Ellen Craft & William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (1860).]

Evil on a grand scale:

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich at War (Penguin Press, 2010).

- Michael Burleigh, Moral Combat: Good and Evil in World War II (Harper/HarperCollins, 2011).

- Madhusree Mukerjee, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II (Basic Books, 2010).

- Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler: A Life (Oxford University Press, 2012); Robert Gerwarth, Hitler’s Hangman: The Life of Heydrich (Oxford University Press, 2012): two books about Nazi SS leaders.

- Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain (W.W. Norton & Company, 2012): an account of Franco’s extermination of 200,000 people for political purposes.

- Peter Godwin, The Fear: Robert Mugabe and the Martyrdom of Zimbabwe (Little, Brown & Company, 2011): a book that gives voice to some of Mugabe’s victims.

- Richard Overy, The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied Air War Over Europe 1940-1945 (Viking, 2014): on the stark moral quandaries in bombing civilian sites during an all-out war.

- Frederick Taylor, Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany (Bloomsbury Press, 2011): “This is a story of Allied acquiescence and even culpability in evil. Delicate subjects like the Allied treatment of German P.O.W.’s . . . were scarcely mentioned in polite company for much of the cold war.”

- Bela Zombory-Moldovan, The Burning of the World: A Memoir of 1914 (NYRB Classics, 2014).

- Bettina Stangneth, Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014): “Like many Nazi mass murderers, he possessed a puritanical petit-bourgeois sense of family and social propriety, indignantly denying that he indulged in extramarital relations or that he profited personally from his duties, and yet he lived quite comfortably with the mass killing of Jews.”

- Caroline Elkins, Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (Knopf, 2022): “Dark Truths About Britain’s Imperial Past”.

Evil on a smaller scale:

- Deborah Scroggins, Emma’s War: Love, Betrayal and Death in the Sudan (HarperCollins, 2003): on the life and death of idealist Emma McCune.

Slavery:

- Andrew Delbanco, The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War (Penguin Press, 2018): “Despite its title, Andrew Delbanco’s ‘The War Before the War’ isn’t so much about confrontation as it is about the earnest, and often self-defeating, methods used to avoid it. In other words, this is a story about compromises — and a riveting, unsettling one at that.”

Corporate greed: The corporate form inherently tends toward the elevation of private interests over the common good. Sometimes this results in profound evil.

- Susan Linn, Who’s Raising the Kids? Big Tech, Big Business and the Lives of Children (The New Press, 2022): “A recurring motif in fairy tales is the parental figure who pretends to care, but in fact sees children as a nuisance, a meal ticket or a meal. Think Hansel and Gretel’s witch, scores of wicked stepmothers or the bonneted wolf in Little Red Riding Hood. (Linn) shows how tech companies like Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and Snapchat have morphed into a society-wide incarnation of these Brothers Grimm monsters. They pose as caregivers, cultivate affection and attachment in children, use psychological insights to prey on their weaknesses, patiently fatten them up — that is, train them in consumption — all the while viewing children as profit centers.”

- Lauren Etter, The Devil’s Playbook: Big Tobacco, Juul, and the Addiction of a New Generation (Crown, 2021): “The story of Juul’s rise and fall teaches us something about greed, capitalism, policy failure and a particular cycle in American business that seems destined to repeat itself.”

- Gerald Posner, Pharma: Greed, Lies, and the Poisoning of America (Avid Reader, 2020): “. . . a withering and encyclopedic indictment of a drug industry that often seems to prioritize profits over patients.”

Hesitate as we might to avoid singling out an individual to personify evil, Joseph Stalin’s cold brutality makes his biographies fit reading on this dark subject.

- Stephen Kotkin, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928 (Penguin Press, 2014).

- Stephen Kotkin, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 (Penguin Press, 2017). “. . . Kotkin teases out his subject’s contradictions, revealing Stalin as both ideologue and opportunist, man of iron will and creature of the Soviet system, creep who apparently drove his wife to suicide and leader who inspired his people.”

- Stephen Kotkin, (a third volume on Stalin is to come).

On the horrors of war in the most turbulent parts of contemporary Africa, and its victims:

- Edward Hoagland, Children Are Diamonds: An African Apocalypse (Arcade Publishing, 2013): on “the 1990s in southern Sudan, where decades of tension have exploded into one of the continent’s most brutal conflicts.”

- Aidan Hartley, The Zanaibar Chest: A Story of Life, Love, and Death in Foreign Lands (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003): “When a Mogadishu mob slaughters four of his friends, he discovers in one of the men's journals these words from Plato: 'Only the dead have seen the end of war.’ Indeed, the Somalia scenes, replete with looting, warlords and swaggering Americans threatening to 'blast this place off the map' and then rebuild it, have a chilling currency.”

- Dave Eggers, What Is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng (First Vintage Books, 2007): “. . . the injustices, horrors and follies that Huck encounters on his raft trip down the Mississippi would have seemed like glimpses of heaven to Eggers’s hero, whose odyssey from his village in the southern Sudan to temporary shelter in Ethiopia to a vast refugee camp in Kenya and finally to Atlanta is a nightmare of chaos and carnage punctuated by periods of relative peace lasting just long enough for him to catch his breath.”

Other narratives of evil:

- David Grann, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the F.B.I. (Doubleday, 2017). First, the United States evicted the Osage people from their land, promising them another tract of land would be theirs forever. Then, when oil was discovered on the reservation, the U.S.A. evicted the Osage from the reservation, murdering many of them.

- Shane Bauer, American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment (Penguin Press, 2018): prison for profit – what could go wrong?

- Behrouz Boochani, No Friend But the Mountains: Writing From Manus Prison (Anansi International, 2019): “During my lifetime no act of the Australian state has been as terrible as the abandonment, the virtual indefinite imprisonment, of 2000 innocent and desperate refugees and asylum seekers on Nauru and Manus Island. . . . Boochani reveals the life of the Manus prisoners in part through the stories of vivid characters all given not names but monikers.”

- Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy, The Forever Prisoner: The Full and Searing Account of the C.I.A.’s Most Controversial Covert Program (Atlantic Monthly, 2022): “Abu Zubaydah is often cited in the vast library of books written about the 9/11 attacks and their legacy, from self-justifying C.I.A. memoirs to angry critiques of the Bush administration. Yet he remains a mysterious figure, because — amazingly — he is still being held incommunicado, in deference to a promise made by the Bush administration to the C.I.A. in 2002. Although he has never been charged with a crime, he sits in a cell in the American prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, his body and mind permanently scarred.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

- City of Life and Death, about the extended 1937-38 massacre in Nanking

- Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, a documentary film about corporate insiders who cared about no one else

- S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (S21: la machine de mort Khmere Rouge), documenting the detention center in Cambodia where innocent people were imprisoned, tortured and killed

- The Missing Picture: another documentary about atrocities in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge

- The Look of Silence: a man obsessively investigates the death of his brother under a murderous anti-Communist regime

- Not My Life, a documentary on human trafficking

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Who were these Thénardiers? Let us say a word or two of them now. We will complete the sketch later on. These beings belonged to that bastard class composed of coarse people who have been successful, and of intelligent people who have descended in the scale, which is between the class called "middle" and the class denominated as "inferior," and which combines some of the defects of the second with nearly all the vices of the first, without possessing the generous impulse of the workingman nor the honest order of the bourgeois. They were of those dwarfed natures which, if a dull fire chances to warm them up, easily become monstrous. There was in the woman a substratum of the brute, and in the man the material for a blackguard. Both were susceptible, in the highest degree, of the sort of hideous progress which is accomplished in the direction of evil. There exist crab-like souls which are continually retreating towards the darkness, retrograding in life rather than advancing, employing experience to augment their deformity, growing incessantly worse, and becoming more and more impregnated with an ever-augmenting blackness. This man and woman possessed such souls. Thénardier, in particular, was troublesome for a physiognomist. One can only look at some men to distrust them; for one feels that they are dark in both directions. They are uneasy in the rear and threatening in front. There is something of the unknown about them. One can no more answer for what they have done than for what they will do. The shadow which they bear in their glance denounces them. From merely hearing them utter a word or seeing them make a gesture, one obtains a glimpse of sombre secrets in their past and of sombre mysteries in their future. This Thénardier, if he himself was to be believed, had been a soldier--a sergeant, he said. He had probably been through the campaign of 1815, and had even conducted himself with tolerable valor, it would seem. We shall see later on how much truth there was in this. The sign of his hostelry was in allusion to one of his feats of arms. He had painted it himself; for he knew how to do a little of everything, and badly. [Victor Hugo, Les Miserables (1862), Volume I – Fantine; Book Fourth – To Confide Is Sometimes to Deliver into a Person’s Power, Chapter II, "The First Sketch of Two Unprepossessing Figures".]

Novels:

- In Sophie’s Choice (1979), William Styron tells of a woman forced to choose which of her children will be executed in a Nazi concentration camp.

- John Steinbeck, East of Eden: A Novel (1952): Steinbeck’s update of the biblical story of Cain and Abel.

- Barry Unsworth, Sacred Hunger: A Novel (Nan A. Talese, 1992): “. . . a vision of hell on earth unlike any in contemporary fiction, largely because its account of the unimaginable cruelties of the slave trade is told in the well-wrought prose of an old-fashioned 19th-century novel with an omniscient narrator.”

- Steve Sem-Sandberg, The Chosen Ones: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016), “recounts the story of a children’s hospital and reformatory in Vienna, Am Spiegelgrund, which functioned from 1940 to 1945 as part of the Nazi medical killing and 'racial hygiene' program.”

- Pete Ayrton, ed., No Man’s Land: Fiction from a World at War: 1914-1918 (Pegasus Books, 2014): “The book’s subtitle is a bit misleading, since the 47 authors sampled here include memoirists and journalists, but Mr. Ayrton has captured the global sweep of the conflict by not awarding undue emphasis to the Western Front already so familiar to us from films and books.”

- Andrew Krivak, The Signal Flame: A Novel (Scribner, 2017): “There is no answer to the question of war, how much it can demand or who should suffer. Krivak, in this moving and eloquent book, reminds us that we are powerless over this presence in our lives. It will return, generation after generation, to our families.”

- Paul Yoon, Run Me to Earth: A Novel (Simon & Schuster, 2020): “Three children, Noi, Prany and Alisak, contemplate their future in a half-destroyed house that has been converted into a makeshift field hospital in war-torn Laos at the end of the 1960s.”

- Riku Onda, The Aosawa Murders: A Novel (Bitter Lemon, 2020): “At a birthday party on a sweltering day in the 1970s, 17 people consume poisoned sake and soft drinks that were delivered as a gift to the wealthy Aosawa family. Only the blind daughter of the household, Hisako Aosawa, doesn’t partake. Instead, she sits and listens as everyone around her moans, vomits and dies in agony. Who instigated this massacre?”

- Ben Hopkins, Cathedral: A Novel (Europa, 2021): “There are plenty of villains in this parade of skirmishes and subterfuges, and few who might pass as heroes.”

- Abdulrazak Gurnah, Afterlives: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2022): “In this story as in history, the German empire is a living, breathing organism with a desire to grow and reproduce and, if threatened, fight for its survival at all costs. Gurnah depicts the white man’s racism plainly: ‘I was born into a military tradition and this is my duty,’ a German officer says to Hamza. ‘That’s why I am here — to take possession of what rightfully belongs to us. … We are dealing with backward and savage people and the only way to rule them is to strike terror into them.'”

- Shehan Karunatilaka, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida: A Novel (W.W. Norton & Company, 2022), “is preternaturally irreverent about the manifold brutalities in Sri Lanka during its 26-year civil war.”

Poetry

Now I tell what I knew in Texas in my early youth,

(I tell not the fall of Alamo,

Not one escaped to tell the fall of Alamo,

The hundred and fifty are dumb yet at Alamo,)

'Tis the tale of the murder in cold blood of four hundred and twelve young men.

Retreating they had form'd in a hollow square with their baggage for breastworks,

Nine hundred lives out of the surrounding enemies, nine times their number, was the price they took in advance,

Their colonel was wounded and their ammunition gone,

They treated for an honorable capitulation, receiv'd writing and seal, gave up their arms and march'd back prisoners of war.

They were the glory of the race of rangers,

Matchless with horse, rifle, song, supper, courtship,

Large, turbulent, generous, handsome, proud, and affectionate,

Bearded, sunburnt, drest in the free costume of hunters,

Not a single one over thirty years of age.

The second First-day morning they were brought out in squads and massacred, it was beautiful early summer,

The work commenced about five o'clock and was over by eight.

None obey'd the command to kneel,

Some made a mad and helpless rush, some stood stark and straight,

A few fell at once, shot in the temple or heart, the living and dead lay together,

The maim'd and mangled dug in the dirt, the new-comers saw them there,

Some half-kill'd attempted to crawl away,

These were despatch'd with bayonets or batter'd with the blunts of muskets,

A youth not seventeen years old seiz'd his assassin till two more came to release him,

The three were all torn and cover'd with the boy's blood.

At eleven o'clock began the burning of the bodies; That is the tale of the murder of the four hundred and twelve young men.

[Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1891-92), Book III: Song of Myself, 34.]

Other poems:

· John McCrae, “In Flanders Field”

· Wilfred Owen, “Dulce et Decorum Est”

· Wilfred Owen, “Anthem For Doomed Youth”

· Robert Frost, “Not to Keep”

· Edgar Lee Masters, “Harry Wilmans”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 13 in B-flat Minor, Op. 113, “Babi Yar” (1962) (approx. 56-70’), in honor of the Jewish peoples. “Throughout his career, Shostakovich used Jewish themes in his music, but his boldest statement of solidarity with Jewish causes was the Symphony No. 13, ‘Babi Yar.’ . . . In 1941, Nazis and their sympathizers murdered nearly 34,000 Jews in two days at Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev. For years, Soviet authorities suppressed any acknowledgement of the atrocity, did not erect a monument, and even went so far as to arrest Jews who prayed at the site. Dissident poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s 1961 poem ‘Babi Yar’ reflects on the massacre and is a searing condemnation of anti-Semitism and the Soviet system that condoned it.” “Most thought they were going to be deported and gathered by the cemetery, expecting to be loaded onto trains. Some even arrived early to ensure themselves a seat. Instead they were ordered towards . . . Babi Yar and once there, made to undress. Those who hesitated had their clothes ripped off by force. They were then systematically shot and hurled into the gorge. If only wounded, they were killed with shovels. Some, especially the children, were just thrown in alive and buried amongst the dead. This continued for five days. Whilst the soldiers rested at night, the remaining victims were locked in empty garages. 33,771 were killed on the first two days. As many as 100,000 in all.” “This was Shostakovich’s last big clash with the State. Mvravinsky refused to conduct it, two basses cancelled, the choir threatened to cancel and eventually Yevtushenko was forced to 'rewrite' the poetry.” Top performances are conducted by Kondrashin in 1962, Maxim Shostakovich in 1995, Neeme Järvi in 1996, Jansons in 2005, Vasily Petrenko in 2014, and Muti in 2018.

Henryk Górecki, Symphony No. 3, Op. 36, “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” (1976) (approx. 49-56’), in memory of Nazi Holocaust victims: “The Third Symphony is composed in three rather than the traditional four movements, each one a dirge of loss. The text of the first movement comes from a fifteenth-century Polish lament of the Holy Cross; the third, from a Silesian folk song of a mother searching for her lost son killed in an uprising. But it is the second movement, the shortest of the three, which has become the focal point of the work. Its text [‘Oh Mamma do not cry — Immaculate Queen of Heaven support me always’] was scrawled on a cell wall at Gestapo headquarters at Zakopane, Poland, by an eighteen-year-old prisoner named Helena Wanda Blazusiakowna.” Excellent performances are by Upshaw with Zinman in 1992, Brewer with Runnicles in 2009, Kilanowicz with Wit in 2012, and Gritton with Simonov in 2012.

Other compositions:

- Alban Berg, Wozzeck (1922) (approx. 80-105’) (libretto begins at p. 46), is an opera about amorality, culminating in murder. “The orderly, Wozzeck, is tormented by his superior, the Captain; by a physician to whom he surrenders himself for medical experiments that he may be able to support his beloved Marie and her child, and by visions rising out of his fantastic reveries. Marie is seduced by the Drum-Major. When Wozzeck, after, torturing uncertainty, has convinced himself of her infidelity, he stabs his beloved and drowns himself.” Excellent performances with video are conducted by Maderna in 1970, and Abbado in 1988; top performances on disc are by Fischer-Dieskau & Lear (Böhm) in 1965, Skavhus & Denoke (Metzmacher) in 1999, and Shore & Barstow (Daniel) in 2003.

- Ernest Bloch, Schelomo, Hebrew Rhapsody for cello and orchestra (1916) (approx. 20-24’): Bloch’s rebirth of the Jewish heritage, seen from a perspective during World War I

- Stephen Hough, The Loneliest Wilderness, Elegy for cello and orchestra (2005) (approx. 17’), is a lament for the death of soldiers.

- Frank Bridge, Oration, Concerto Elegiaco for solo cello and orchestra (1930) (approx. 29-32’), is a pacificist’s musical commentary on the futility and devastation of war.

- Mohammed Fairouz, Symphony No. 4, "In the Shadow of No Towers" (2012) (approx. 36-40’), “takes its inspiration from details in Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel of the same name and evokes the cataclysm of September 11, 2001, and its repercussions over the years.”

- Taune Kullervo Pylkkänen, Mare ja hanen poikansa (Mare and Her Son), Op. 22 (1943) (approx. 138’), on the tragedy and futility of war: a mother who has lost six of her seven sons to war tries to save the life of her youngest but she makes moral compromises to do it, and no one is spared.

- Wolfgang Rihm, Die Eroberung von Mexico (The Conquest Of Mexico) (1992) (approx. 108’), is an opera about the brutality and arrogance of Christian-European imperialism.

- Joly Braga Santos, Symphony No. 1 in D Major, “To the Heroes and Martyrs of the last World War”, Op. 9 (1947) (approx. 36-37’): dedicated “to the memory of the Heroes and Martyrs of the last world war”

- Heiner Goebbels, The Horatian – Three Songs (1992) (approx. 16’): one man slays another when he could have spared him.

- Charles Martin Loeffler, La Mort de Tintagiles, Op. 6 (1897) (approx. 23-26’), after Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, “The Death of Tintagiles” (1894), in which no one can save Tintagiles, who is killed on the order of a ruthless Queen.

- Matthew AuCoin, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (2016) (approx. 37’): “The music is so filled with suspense, so frightening in its exploration of the unknown that it made this listener feel as if the entire world threatened to close in without notice.”

- Alexander Kastalsky, Requiem for Fallen Brothers (1915) (approx. 64’), was written “to memorialize the Entente lives lost during World War I. While the seventeen-movement requiem was completed in 1917, it was—with the advent of Russia’s revolutions and the subsequent Communist-enforced secularism that banned all performances of sacred music—never performed in its entirety.”

- Heitor Villa-Lobos, Symphony No. 3, “A Guerra” (War) (1919) (approx. 32-51’)

- Jake Runestad, Dreams of the Fallen (2013) (approx. 26’) is a choral-orchestral work “that explores a soldier’s emotional response to the experience of war using powerful texts written by Iraq War veteran and award-winning poet Brian Turner.”

- Žibuoklė Martinaitytė, Aletheia (2022’) (approx, 15’) is “a rallying cry for humanity”, written by a Lithuanian composer as Russia was invading Ukraine.

- Martinaitytė, Ululations (2023) (approx. 13-14’): “Martinaitytė writes that her work “Ululations” portrays ‘mourning women whose men… are at war fighting and dying.’” It expresses the “. . . idea of ululations as an audible, ritualistic expression of mourning . . .”

- Thomas de Hartmann, Violin Concerto, Op. 66 (1943) (approx. 30’), “expresses the devastation of Ukraine in World War II . . .”

- Thomas de Hartmann, Cello Concerto (1935) (approx. 36’) “was composed in 1935, inspired by the anxiety of the 1930s, linking the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany to de Hartmann’s own recollections of local Jewish folk musicians.”

Albums:

- Reg Meuross, “Stolen from God” (2023) (47’), is about the Transatlantic slave trade. “The album adeptly navigates its way through a series of narratives and characters, some fictional, others not, who either deliver unapologetic lectures that seek to justify their actions . . . or bring to light the inequality of treatment for those men and women who were forced to forge new lives that they neither sought nor desired . . .”

- John Carter, “Castles of Ghana” (1985) (48’): “The second of clarinetist John Carter's five-part depiction of the history of African Americans deals with the capture of many Africans for shipment as slaves to the New World.”

- ØXN, “CYRM” (2023) (46’) (lyrics): the six tracks are “full of unsettling dark magic.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Franz Schubert (composer), "Der Vatermörder" (The Parricide), D. 10 (1811) (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Jackson Pollock, Lucifer (1947)

- Salvador Dali, The Visage of War (1941)

- Pablo Picasso, La Guernica (1937)

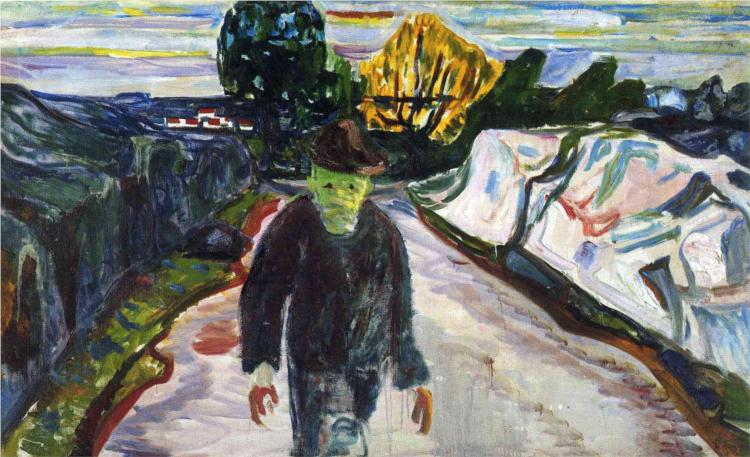

- Edvard Munch, The Murderer in the Lane (1919)

- Lucifer

- William Blake, Good and Evil Angels Struggling for Possession of a Child (1793)

Film and Stage

- All Quiet on the Western Front (and its equally excellent remake), about the horrors of war

- Apocalypse Now, on war as a “descent into primal madness”

- Come and See(Idi i smotri), telling of the horrors of World War II from the Soviet side and through a young teen’s eyes

- The Deer Hunter, social commentary on the Vietnam War

- The Big Red One, on World War II as “the biggest crime story of the century”

- Paths of Glory, about the execution of three soldiers for cowardice to cover for a vain general’s folly

- Full Metal Jacket: a gritty take on the Vietnam War, as seen from the ground

- Platoon, “a brutally realistic look at a young soldier's tour of duty in Vietnam”

- The Burmese Harp (Biruma no Tategoto): This engaging but flawed Japanese film (you don’t get rich sound like that from the few-stringed instrument in the film, especially after it is thrown around like a bean bag, not to mention that it won’t produce that many tones), about a harp-playing soldier in the final days of World War II and after, does not fit under the heading of transformation because the gentle harpist never changes character; and it doesn’t fit under service because he remains in Burma out of compassion for the dead. Mainly, it is an anti-war film, as expressed by the graphic images of war’s aftermath.

- L’Argent (Money), “a ruthless tale of greed, corruption and murder”

- Baby Doll, “about decadence in the South”

- Blue Velvet, a bug’s-eye view of evil

- Casque d’or: jealousy, power, deceit, sex and the framing of an innocent man

- East of Eden: based on the biblical Cane and Abel story

- Force of Evil: a man chooses between money and family

- The Night of the Hunter: two farm kids and a pious lady battle a psychopath

- Z, a cinematic treatment of true events surrounding a government plot in Greece to kill a man whose pacifist views were inconvenient to the government in power and the country’s right wing

- The Stoning of Soraya M, a dramatization of the stoning of an innocent woman in a radically Islamic village

- Billy Budd, on the profound injustice of a society built around principles of war

- City of Life and Death is among the most difficult to watch of all films, portraying in detail the Rape of Nanking in 1937.