- . . . that sad but easeful core of peace that is the reward when all is renounced. [Maestro Benjamin Zander commenting on the solo cello statement near the end of the final movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony]

No doubt many of my Humanist sisters and brothers will protest the idea of surrender. Perhaps this will encourage them to reconsider. Spiritual surrender does not refer to giving up a political battle or a struggle for justice; it is simply the deep and peaceful acceptance of those things we cannot change. Then we can direct our attention to moving forward.

Here is a series of videos on spiritual surrender.

Real

True Narratives

Book narratives:

- Nastassja Martin, In the Eye of the Wild (New York Review Books, 2021): “What Martin describes in this book isn’t so much a search for meaning as an acceptance of its undoing.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Éponine’s death:

She was sitting almost upright, but her voice was very low and broken by hiccoughs. At intervals, the death rattle interrupted her. She put her face as near that of Marius as possible. She added with a strange expression:-- "Listen, I do not wish to play you a trick. I have a letter in my pocket for you. I was told to put it in the post. I kept it. I did not want to have it reach you. But perhaps you will be angry with me for it when we meet again presently? Take your letter." She grasped Marius' hand convulsively with her pierced hand, but she no longer seemed to feel her sufferings. She put Marius' hand in the pocket of her blouse. There, in fact, Marius felt a paper. "Take it," said she. Marius took the letter. She made a sign of satisfaction and contentment. "Now, for my trouble, promise me--" And she stopped. "What?" asked Marius. "Promise me!" "I promise." "Promise to give me a kiss on my brow when I am dead.--I shall feel it." She dropped her head again on Marius' knees, and her eyelids closed. He thought the poor soul had departed. Éponine remained motionless. All at once, at the very moment when Marius fancied her asleep forever, she slowly opened her eyes in which appeared the sombre profundity of death, and said to him in a tone whose sweetness seemed already to proceed from another world:-- "And by the way, Monsieur Marius, I believe that I was a little bit in love with you." She tried to smile once more and expired. [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume IV – Saint-Denis; Book Fourteenth – The Grandeurs of Despair, Chapter VI, The Agony of Death After the Agony of Life.]

Poetry

Let me die and not tremble at death, / But smile at the close of my day, / And then, at the flight of my breath, / Like a bird of the morning in May, / Go chanting away.

Let me die without fear of the dead, / No horrors my soul shall dismay, / And with faith's pillow under my head, / With defiance to mortal decay, / Go chanting away.

Let me die like a son of the brave, / And martial distinction display, / Nor shrink from a thought of the grave, / No, but with a smile from the clay, / Go chanting away.

Let me die glad, regardless of pain, / No pang to this world to betray; / And the spirit cut loose from its chain, / So loath in the flesh to delay, / Go chanting away.

Let me die, and my worst foe forgive, / When death veils the last vital ray; / Since I have but a moment to live, / Let me, when the last debt I pay, / Go chanting away.

[George Moses Horton, “Imploring to be Resigned at Death”]

Other poems:

- John Milton, “On His Blindness”

- Faiz Ahmed Faiz, “Some Lover To Some Beloved!”

Poetry books:

- Victoria Chang, Obit: Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 2020): “After her mother died, poet Victoria Chang refused to write elegies. Rather, she distilled her grief during a feverish two weeks by writing scores of poetic obituaries for all she lost in the world. In Obit, Chang writes of 'the way memory gets up after someone has died and starts walking.'”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Gustav Mahler knew he was dying of a cardiac ailment when he composed his Ninth Symphony in 1908-09 (approx. 70-88’). “We also know that he struggled all his life—first as a Jew, then as a Roman Catholic—with notions of spiritual salvation; that for him the likelihood that life was a grotesque and bitter struggle (or even a meaningless joke) was always in conflict with a deep sense of hope, piety, joy and love.” “. . . Mahler ends the ninth with a slow movement, neither a triumphant conclusion, nor an apotheosis, but a fervent prayer for the survival of the human spirit, subjected to the destructive power of negative forces within it. That prayer will conclude not in hopeless resignation, but with an acceptance of life that encompasses its negative as well as positive aspects, and thereby recalls the underlying philosophy of Das Lied.” Benjamin Zander’s exegesis on this heart-rending symphony expresses the musical ideas and their relation to life brilliantly. Great performances have been conducted by Walter in 1938, Horenstein in 1952, Walter in 1961, Barbirolli in 1964, Ančerl in 1966, Horenstein in 1966, Klemperer in 1967, Szell in 1969, Haitink in 1970, Bernstein in 1979, Kurt Sanderling in 1982, Karajan in 1982, Boulez in 1997, Gielen in 1999, and Rattle in 2007.

Below are my interpretations, the first a brief summary of the final movement, the second a more detailed consideration of the entire symphony.

- Mahler's farewell to love and life [compare the opening theme to that in Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 26 in E flat major, "Les adieux"]

- the protagonist struggles to survive

- but death will not be denied

- resolultion: acceptance and surrender

- questions linger

- finally, all sound subsides, symbolizing death; “Grief gives way to peace, music and silence become one.”

Extended analysis of Mahler's Ninth Symphony:

- First movement (0:48): The first few bars sound the existential question of life, flavored with its everyday affairs, followed by a theme expressing life's poignancy. Conflict arises and the hero struggles with it. Life returns to normal and then becomes exuberant, which for Mahler was normal. We hear an opening to love and then a reminder that it comes amid everyday life. A quiet but ominous warning sounds. Adversity strikes but we persevere. A great personal battle ensues, and then gives way to tragedy and dread. Other voices mock the agony. The hero gathers himself and waits. Finally, love emerges, someone with whom to share life's joys and sorrows; someone who tempers the force of their blows. Every voice seems to affirm and reinforce the newfound love. But nothing remains simple for long. Is this tragedy or merely uncertainty? Is the struggle real or imagined? In Mahler's world, with its rich emotional character, it could be either. The mallet tells us that tragedy has struck. Brass voices mock the misery. Discordant sorrow taints the love theme. The hero is tortured with grief. Love struggles to re-emerge but nothing can contain Mahler's anguish. Another tragedy strikes, perhaps invoking the death of Mahler's daughter at the age of four, a loss from which Mahler never recovered. This time, the love's gentle voice seems to have forgotten her theme altogether; only her sweet voice remains, and only for a moment. The hero struggles to find acceptance. Is the love theme seeking to re-emerge, or is it being mocked? Finally, it reappears but now the voices of dread accompany it. They pick up and distort the theme. There seems to be no escape from life's vagaries. The hero reflects on life. The will is strong, expressing itself in a brief statement of happiness, which is quickly swallowed by circumstance. The love theme is remembered but no longer satisfies. Then love re-emerges with a varied theme and deeper sense of poignancy. Joy and sorrow are barely distinguishable. The hero has found his voice again but now it is laden with sorrow. Notes of acceptance begin to sound as the first movement fades to its conclusion.

- Second movement (28:20): A playful ländler (rustic dance) theme reminds us that life goes on. Life is both tragic and farcical. The brass run is rushed, suggesting a child-like eagerness to engage. The love theme sounds amid the revelry. Farce again, then a reminder. Now the hero participates fully in the farcical dance. Love and seriousness of purpose sound again. Like a man on a highwire, the protagonist navigates between playfulness and calamity. Life is a grotesque dance, foreshadowing death - intermittently comical and maniacal - and ending in pointless absurdity. Or is humor the point?

- Third movement (44:40): Continuing the narrative theme of tragic farce, this movement is an extended rondo-burleske, sounding as though the champion of life had forgotten about his inner life and busied himself, as most of us do, with the mundane. The solo trumpet expresses the protagonist's longing and pathos again. The theme of longing repeats and then the humdrum of life interferes with living again. The busy-ness of this movement leaves us unprepared for what is to follow.

- Fourth movement (56:22): Mahler wore his passionate love for his wife Alma on his shirtsleeve. Most of his symphonies contain extended sections, sometimes entire movements, devoted to his feelings for her. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the extended first section of this fourth movement, an adagio. In it, Mahler expresses his gratefulness for Alma's love and companionship, suggesting that it has tempered the tragedy that is so palpable to him. The melody suggests the popular song "Abide With Me," which Mahler probably heard while he was conducting in the United States. Though Mahler's sadness is palpable, so is his joy. Ominous tones from the bassoon foreshadow tragedy. The French horn expresses the hero's resolute courage. Passion cannot be contained but eventually, death will not be denied. The solo flute suggests another way of looking at life, as though our hero was bargaining with nature. Now the French horn sounds resigned but yet there is hope while we live. Leonard Bernstein conducts these bars with a passionate sense of meaning and purpose and expresses the core of the music. "I want more!" the hero seems to cry out. A gentle reminder intervenes, perhaps soothes. The volume begins to dim, suggesting the final decline. Again, a hint of resolution. The dignity of acceptance precedes the hero's staunch insistence that he wishes to live. Every tone lingers, as the hero struggles to hold on. Though death is inevitable, undaunted resolve is a triumph of sorts - or perhaps this is the moment of final recognition and acceptance. The love theme returns, changed perhaps by the reality of impending death. The solo cello poses a final question, and then silence slowly and gradually engulfs the soul.

Richard Strauss, Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration), Op. 24 (1889) (approx. 25’), depicts an artist’s death, as Strauss imagined it in his youth. This is from a letter Strauss wrote, describing the work: “It was six years ago when the idea came to me to write a tone poem describing the last hours of a man who had striven for the highest ideals. The sick man lies in bed breathing heavily and irregularly in his sleep. Friendly dreams bring a smile to the sufferer; his sleep grows lighter; he awakens. Fearful pains once more begin to torture him, fever shakes his body. When the attack is over and the pain recedes, he recalls his past life; his childhood passes before his eyes; his youth with its striving and passions and then, while the pains return, there appears to him the goal of his life’s journey, the idea, the ideal which he attempted to embody, but which he was unable to perfect because such perfection could be achieved by no man.” “Though Strauss himself had adopted a decidedly secular worldview as a teenager, he brilliantly depicted the physiological and psychological states of a dying man with almost scientific precision, using the most advanced orchestrations and harmonies of his time. The piece was not based on any personal experience, but intriguingly, on his deathbed Strauss remarked that 'dying is exactly as I composed it sixty years ago in Tod und Verklärung.'” Strauss conducted the work in 1926 (begin at 40:30). Top recordings are conducted by Szell in 1959, von Karajan in 1983, Levine in 1995, Zinman in 2000, and Jansons in 2014.

Franz Joseph Haydn, Die sieben letzten Worte unseres Erlösers am Kreuze (The Seven Last Words of Our Savior on the Cross), Hob. XXI:1 (1786) (approx. 90’), offers an eighteenth-century theistic take on spiritual surrender. Per Haydn’s explanation, the seven “words” refer to statements attributed to Christ as he was being crucified. The work “comprises an introduction, seven slow movements corresponding to the seven words, and a musical depiction of the earthquake following the crucifixion.” “The seven Sonatas take us deep into a meditative space, akin to the chapel’s somber underground cave. (Haydn never visited Cádiz). As the music unfolds, wrenching anguish and lament combine with a sense of serene majesty and transcendence.” Orchestral and choral versions [XX:2 (1796)], as well as a version for string quartet [Op. 51, Hob. III:50-56 (1787)], have received considerable attention. Excellent performances of the orchestral version are conducted by Storgårds in 2002, Savall in 2009; and Minasi in 2019 ***. Excellent performances of the choral version are conducted by Scherchen in 1962, Harnoncourt in 1990 ***, and Equilbey in 2006. Excellent performances of the string quartet version are by Primrose Quartet ca. 1940, Kodály Quartet in 1989, Quatuor Mosaïque in 1991, Borodin Quartet in 1993, Talich Quartet in 1995, Emerson String Quartet in 2002, Pražák Quartet in 2011, and Cuarteto Casals in 2013.

Other compositions:

- Gavin Bryars, “A Native Hill” (2019) (approx. 69’) is a choral song cycle based on an essay by Wendell Berry, ends with these words from the final song, titled “At Peace”: “Days, winds, seasons pass over me as I sink under the leaves. For a time only sight is left me, a passive awareness of the sky overhead, birds crossing, the mazed interreaching of the treetops, the leaves falling – and then that, too, sinks away. It is acceptable to me, and I am at peace. When I move to go, it is as though I rise up out of the world.” It is about surrendering to and accepting our place in nature.

- Carl Nielsen, Clarinet Concerto, Op. 57 (1928) (approx. 23-25’) “is his only large symphonic work which begins and ends in the same key (F), purposefully avoiding his 'progressive tonality' resolution. . . this is because he had become resigned to the power of death’s inevitable grip on his life.”

- Jean Gilles, Messe des Morts (Requiem) (1697) (approx. 80-86’): This gentle requiem stands alone.

- Michael John Trotta, Seven Last Words (Septum Ultima Verba) (2017) (approx. 41’) “is a seven-movement choral journey through the Passion . . .”

- Arthur Bliss, Two Studies for Orchestra, Op. 16, F133 (1920) (approx. 11-12’): resolution

- Richard Wetz, Requiem in B Minor, Op. 50 (1925) (approx. 60-70’): the text is that of a traditional Christian requiem but the music evokes acceptance.

- Laurence Lowe, Sonata for Violin and Piano (approx. 24’)

- Vito Palumbo, Violin Concerto (2015) (approx. 31’) “displays bittersweet lyricism”. “A final and evidently defining climax proceeds its dying down towards the musing and even mystical serenity with which this work closes.”

- Jaakko Kuusisto, Symphony, Op. 39 (2022) (approx. 27’), draws its inspiration from the composer’s diagnosis with a fatal brain tumor.

Albums:

- Laurel Premo, “Golden Loam” (2021) (53’): “Premo has a gentle touch that conveys a well of strength and feeling. Across these 10 tracks, an intimacy emerges from early morning fog, split between the tree boughs and creek beds.”

- Ludovico Eunaudi’s “Divenire” (2006) (82’) is poignant and beautiful, touching the soul with fond but sad remembrance.

- John Rutter, “Anthems, Hymns and Gloria for Brass Band” (2020) (62’)

- Ola Gjeilo, “Winter Songs” (2017) (54’). Gjeilo has said of the album: “I don't know if there's a specific peak. It's more like the center of it to me is a track called 'Home.' It's the shortest piece on the album, less than two minutes, and it's an instrumental with piano and strings. That track is just really close to my heart.”

- Jon Irabagon, “Behind the Sky” (2015) (76’): “The grieving process is a personal journey and an act of discovery, allowing individuals to truly appreciate what was, while awakening to the reality of what is.”

- Avishai Cohen, “Naked Truth” (2022) (35’), is a musical meditation on accepting what we cannot change.

- Steven Halpern, “Transitions: Music for Comfort and Solace in times of loss and grief” (2000) (63’)

- Han Seong Seuk & Jung Jae-Il, “And There, The Sea at Last” (2017) (61’)

From the dark side:

- Erich Korngold, Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) (1917) (approx. 129-137’): A man obsesses over his deceased wife. No good comes of it.

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Arvo Pärt (composer), “Spiegel im Spiegel”

- Maurice Ravel (composer), “Pavane pour une infante défunte” (Pavane for a Dead Princess)

- Bonnie Raitt, “I Can’t Make You Love Me” (lyrics)

- Hugo Wolf (composer), “Komm, o Tod, von Nacht umgeben” (Come, O Death, Shrouded in Night), from Spanisches Liederbruch (No. 34), Weltliche Lieder (No. 24) (1890)

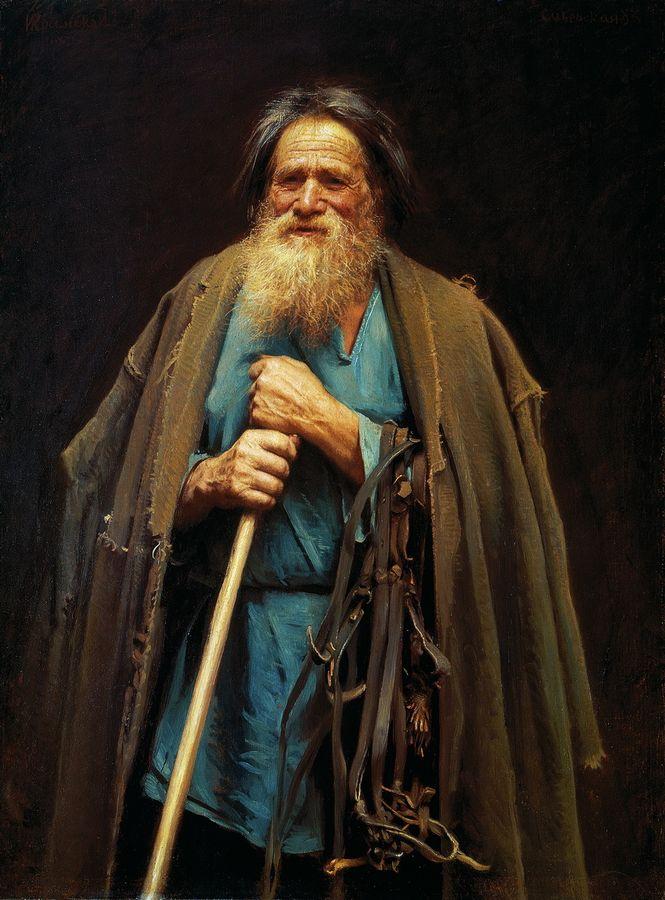

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- The Sweet Hereafter: a community copes with death of children after a bus accident

- In America: a hard-knocks film about a young Irish couple and their small children coming to the United States, struggling to survive in New York City, and working their way, blindly, toward acceptance of the death of their two-year-old son.