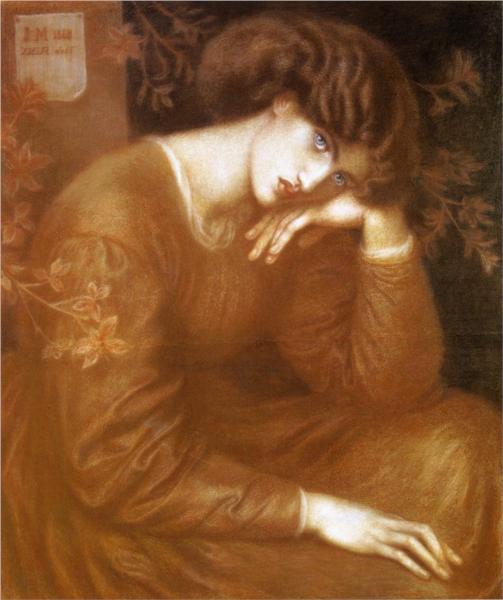

Reverie is a dreamy or musing state. When we calm ourselves emotionally and mentally, we allow our minds to engage in the relaxing play called reverie.

Real

True Narratives

|

I have sat for hours in a sort of reverie, letting my mind have its way without inhibition and direction, and idly noted down the incessant beat of thought upon thought, image upon image. I have observed that my thoughts make all kinds of connections, wind in and out, trace concentric circles, and break up in eddies of fantasy, just as in dreams. One day I had a literary frolic with a certain set of thoughts which dropped in for an afternoon call. I wrote for three or four hours as they arrived, and the resulting record is much like a dream. I found that the most disconnected, dissimilar thoughts came in arm-in-arm--I dreamed a wide-awake dream. The difference is that in waking dreams I can look back upon the endless succession of thoughts, while in the dreams of sleep I can recall but few ideas and images. I catch broken threads from the warp and woof of a pattern I cannot see, or glowing leaves which have floated on a slumber-wind from a tree that I cannot identify. In this reverie I held the key to the company of ideas. I give my record of them to show what analogies exist between thoughts when they are not directed and the behaviour of real dream-thinking. [Helen Keller, The World I Live In (1907), chapter XV, “A Waking Dream.”] |

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Patrick Modiano, Sleep of Memory: A Novel (Yale University Press, 2018): “The Nobel laureate’s dreamlike novels summon elusive, half-forgotten episodes. Here, that means Paris in the ’60s, love affairs, a flirtation with the occult and a shocking crime.”

- Asali Solomon, The Days of Afrekete: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021): “Solomon’s novel is a feat of engineering. It’s also a reverie, a riff on ‘Mrs. Dalloway’ and a love story. In Liselle, Solomon has invented a character who comes to the mind’s eye in HD, with anxieties, jokes, memories, furies and survival instincts all present in prose as clear as water.”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Frédéric Chopin’s twenty-one Nocturnes for solo piano (1833-1855) (approx. 108-122’), as a whole, capture the spirit of reverie, though a few of them are tumultuous. “The Italian term ‘notturno’ (‘night piece’) was used in the eighteenth century to mean music for evening entertainment . . .” “The form originated a generation earlier with the English composer-pianist, John Field (1782-1837). Chopin’s Nocturnes become magical and atmospheric ‘songs of the night.’ They are bel canto arias without words, in which the piano is transformed into a singing instrument.” This is music for a warm summer evening, with your windows open. Top recorded performances are by Arthur Rubinstein in 1957, Claudio Arrau in 1967, Maurizio Pollini in 1986, Maria João Pires in 1989, Brigitte Engerer in 1993, Nelson Friere in 2006, Yundi Li in 2010, Nelson Goerner in 2017, and Jan Lisiecki in 2021.

Gabriel Fauré composed thirteen Nocturnes for solo Piano over a span of thirty-six years (1875-1921) (approx. 75-92’). These works are prime examples of French impressionism, with its inherently dream-like quality. “Whilst the appellation ‘Nocturne’ is neutral rather than evocative, it is quite clear that ‘Nocturne’ was chosen for piano pieces of the greatest emotional weight and depth, ranging from the poised equilibrium of No. 4 to the great struggle of No. 13, from the long lines of No. 7 to the terse and epigrammatic No. 9, from the uninterruptedly radiant flow of No. 3 to the inarticulateness of No. 10, from the serenity of No. 6 to the anguish and torment of No. 12.” Top recorded performances are by Germaine Thyssens-Valentin in 1956, Jean-Philippe Collard in 1974, Paul Crossley in 2002, and Marc-André Hamelin in 2023.

As most commonly interpreted today and for many years, Ludwig van Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, (Sonata quasi una fantasia, “Moonlight”, Op. 27, No. 2 (1801) (approx. 10-17’), evokes a romantic moonlit evening. The too-slow tempo in most modern interpretations (e.g., Rubinstein and Backhaus) was not what Beethoven intended. Each phrase was supposed to be connected to the next, as though the phrases were building a bridge, with the main chord in each phrase bringing the bridge together. A performance by Glenn Gould retained much of romantic quality without sacrificing Beethoven’s intent. “At the time of writing ‘Moonlight,’ Beethoven’s life was at a breaking point due to several factors. To name just a few, he realized that his worsening deafness might never be cured. He was deeply in love with one of his students (seventeen-year-old Countess Giulietta Gucciardi), who two years later married another man. ‘Moonlight’ Sonata was dedicated to her.” “. . . when the German critic Ludwig Rellstab described the sonata’s famous opening movement as being akin to moonlight flickering across Lake Lucerne, he created a description that would go on to outlive the composer.” Top recorded performances are by. Harold Bauer in 1927, Artur Schnabel in 1933, Claudio Arrau in 1962, Wilhelm Kempff in 1965, Alfred Brendel in the 1960s, Radu Lupu in 1972, Emil Gilels in 1980, Daniel Barenboim in 1984, Richard Goode in 1990, Maurizio Pollini in 1992, Ronald Brautigam in 2006, Nelson Friere in 2006, Paul Lewis in 2007, Stewart Goodyear in 2010, Alessio Bax in 2013, Stephen Hough in 2013, Murray Perahia in 2017, Igor Levit in 2019, Valentina Lisitsa in 2020, and Alice Sara Ott in 2023.

Other compositions:

- Arthur Foote, Nocturne and Scherzo for Flute and String Quartet (1918) (approx. 13’) “is a rhapsodic fantasy, formally articulate in its alternation of passages led by the flute with sections for the strings alone.”

- Nicolas Flagello, Nocturne for Violin and Piano (1969) (approx. 6’)

- Carlos Salzedo, music for harp: Antonella Ciccozzi, “Iridescence” album (2021) (52’)

- Leoš Janáček, In the Mists, (V mlhách) JW VIII/22 (1912) (approx. 14-16’): In the Mists “paints a mesmerizingly foggy atmosphere that, upon closer look, is hiding all kinds of imagery and imagination.”

- Sergei Rachmaninoff, Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 36 (1913, rev. 1931) (approx. 20-23’)

- Almeida Prado, 14 Nocturnes for piano (1985-1991) (approx. 52’): “Along with abstract elements and features such as synesthesia, used in homage to his teacher Messaien, the full range of influences can be felt in Almeida Prado’s Nocturnes: Chopin, Scriabinesque colour, bossa-nova, Brahms-like intervals, serenity and radiant songfulness.”

Albums:

- Kevin Kern, “Summer Daydreams” (1998) (48’): “There are no pianistic pyrotechnics here, but there is an abundance of warmth and sincerity to soothe the mind and calm the spirit.”

- Jakob Bro, “Uma Elmo” (2021) (62’): “Like the music, Bro's album title is very personal; it is made up of the middle names of his children. The youngest is seven months old, and much of the music was composed during his naps as a newborn.”

- Katherine Priddy, “The Eternal Rocks Beneath” (2021) (41’): “To listen to The Eternal Rocks Beneath is to sink into a reverie. Elemental and evocative, the much-anticipated debut from Katherine Priddy finds the Birmingham-based singer/songwriter putting a contemporary spin on the mythological.”

- Arushi Jain, “Under the Lilac Sky” (2022) (49’): “Throughout the album, these percussion-less tracks are propelled by their own sense of momentum, grounded by the pace of Jain’s repeating synth patterns and the reassuring constant of her vocal melodies, heard with particularly piercing clarity in the bass-led My People Have Deep Roots.”

- Ludovico Einaudi, “Islands: Essential Einaudi” (2011) (77’)

- Boston Modern Orchestra Project, “Keeril Makan - Dream Lightly” (2019) (61’): “Composer Keeril Makan contextualizes silence, connects past and present, and explores dream states and reality . . .”

- Mikael Máni, “Guitar Poetry” (2024) (32’)

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Simon & Garfunkel, “59th Street Bridge Song” (lyrics)

- Rachmaninoff, 14 Romances, “Vocalise”, Op. 34, No. 14 (performances by Dessay, Shafran and Chang)

Visual Arts

- Salvador Dali, White Calm (1936)

- Salvador Dali, Boat (1918)

- Isaac Levitan, Twilight Moon (1899)

- Alphonse Mucha, Evening Reverie (nocturnal slumber) (1898)

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Boating at Argenteuil (1873)

- Ivan Aivazovsky, Moonlit Night (1849)