Time away from a thing vigorously pursued can refresh.

- I have walked myself into my best thoughts, and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it. [Søren Kierkegaard, Letter 150 (1847).]

- A holiday is an opportunity to journey within. It is also a chance to chill, to relax. It is when I switch on my rest mode. [attributed to Prabhas]

- A vacation is what you take when you can no longer take what you’ve been taking. [attributed to Earl Wilson]

To retreat is to remove ourselves physically, intellectually and emotionally from our cares, usually for an extended time. It reduces stress, recharges mind and body, gives the physical heart a rest, and generally improves well-being, for a while. Meditating while on retreat extends the time over which a vacation yields positive mental health benefits. “For those already trained in the practice of meditation, a retreat appears to provide additional benefits to cellular health beyond the vacation effect.” The most effective way to get away is to get away from work completely. We could call it a vacation for the soul and spirit.

Real

True Narratives

The cartoon as a vehicle for light-hearted escape:

- Cullen Murphy, Cartoon Country: My Father and His Friends in the Golden Age of Make Believe (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2017): “In Murphy’s reckoning, cartoonists are no more or less indispensable to society than the dentists and adjusters they evidently resemble. They simply play their part.”

- Hillary L. Chute, Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere (Harper, 2017): “Chute sees comics as a sequential medium, which at its heart ‘is about distillation and condensation.’”

- Jon Morris, The League of Regrettable Superheroes: Half-Baked Heroes from Comic Book History! (Quirk Books, 2015).

- Jon Morris, The League of Regrettable Sidekicks: Heroic Helpers and Malicious Minions from Comic Book History! (Quirk Books, 2018).

- Jon Morris, The Legion of Regrettable Supervillains: Oddball Criminals from Comic Book History! (Quirk Books, 2017).

- Hope Nicholson, The Spectacular Sisterhood of Superwomen: Awesome Female Characters from Comic Book History (Quirk Books, 2017).

- Dan Mazur & Alexander Danner, Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present (Thames & Hudson, 2014).

- Shirrel Rhoades, A Complete History of American Comic Books (Peter Lang, Inc., 2008).

- Jeremy Dauber, American Comics: A History (W.W. Norton and Company, 2021): “A Sweeping History of American Comics”.

- Douglas Wolk, All of the Marvels: A Journey to the Ends of the Biggest Story Ever Told (Penguin Press, 2021): “He Read All 27,000 Marvel Comic Books and Lived to Tell the Tale”.

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Poetry

A little while, a little while,

The weary task is put away,

And I can sing and I can smile,

Alike, while I have holiday.

Where wilt thou go, my harassed heart—

What thought, what scene invites thee now

What spot, or near or far apart,

Has rest for thee, my weary brow?

There is a spot, ’mid barren hills,

Where winter howls, and driving rain;

But, if the dreary tempest chills,

There is a light that warms again.

The house is old, the trees are bare,

Moonless above bends twilight’s dome;

But what on earth is half so dear—

So longed for—as the hearth of home?

The mute bird sitting on the stone,

The dank moss dripping from the wall,

The thorn-trees gaunt, the walks o’ergrown,

I love them—how I love them all!

Still, as I mused, the naked room,

The alien firelight died away;

And from the midst of cheerless gloom,

I passed to bright, unclouded day.

A little and a lone green lane

That opened on a common wide;

A distant, dreamy, dim blue chain

Of mountains circling every side.

A heaven so clear, an earth so calm,

So sweet, so soft, so hushed an air;

And, deepening still the dream-like charm,

Wild moor-sheep feeding everywhere.

That was the scene, I knew it well;

I knew the turfy pathway’s sweep,

That, winding o’er each billowy swell,

Marked out the tracks of wandering sheep.

Could I have lingered but an hour,

It well had paid a week of toil;

But Truth has banished Fancy’s power:

Restraint and heavy task recoil.

Even as I stood with raptured eye,

Absorbed in bliss so deep and dear,

My hour of rest had fleeted by,

And back came labour, bondage, care.

[Emily Brontë, “A little while, a little while”]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Medieval and some traditional music from the Near East, in the region of Armenia, gives a sense of visiting a long-forgotten place. A melancholy undertone in this music adds a sense of mystery. Leading exponents of this music include

- Anouar Brahem, with his playlists;

- Djivan Gasparyan, with his playlists;

- Emre Gültekin, with his releases; and

- Vardan Hovanissian, with his playlists;

- Munir Bashir, with his releases;

- Omar Bashir, with his releases and his playlists;

- Simon Shaheen, with his playlists;

- Ara Topouzian, with his playlists; and

- Hasmik Bhagdasaryan, with her playlists.

Sometimes these artists have paired, as on the following albums:

- Djivan Gasparyan & Ergan Okur, “Fuad” (2001) (59’)

- Hossein Alizadeh & Djivan Gasparyan, “Endless Vision” (2005) (52’): “What the music amounts to is a space out of time, where the past lives eternally into the present and the present gives up its preoccupations with future. The music itself is poetic, full of space, haunting modes, and spiritual melody that is as rooted in the body as love itself is.”

- Vardan Hovanissian & Emre Gültekin, “Adana” (2015) (59’): “The playing is exquisite (and there are gifted guests), the mood contemplative and nostalgic, drawing on folk melodies, poems and original pieces celebrating miners and murdered journalist Hrant Dink.”

- Vardan Hovanissian & Emre Gültekin, “Karin” (2018) (52’): the album title “refers to the birthplace of Vardan Hovanissian’s grandfather, who was one of 200 survivors following the deportation of around 40,000 people during the Armenian genocide. The album is dedicated to the cosmopolitan period in Karin, which was a meeting place for the different cultures that existed along the Silk Road.”

- Wouter Vandenabeele, Joris Vanvinckenroye, Ertan Tekin and Emre Gültekin, “Chansons pour le fin d’un jour” (Songs for the End of the Day) (2010) (46’)

Jordi Savall with his Hespèrion ensembles, have created the following albums and live peformances along the same lines:

- “Armenian Spirit” (2012) (77’)

- “Jerusalén: La Cuidad de los Paces” (The City of the Fish) (2010) (128’)

- “Estembul: El libro de la cienca de la música” (2011) (49’)

Similar to the foregoing artists, albums and performances, are the following artists, who infuse traditional music with popular/contemporary flavors. For traditionalists, this ruins the effect but for many people, it provides an introduction into the music that is less jarring than a jump into frigid water.

- Dhafer Youssef, with his releases;

- Ara Dinkjian, with his playlists;

- Hossein Alizadeh, with his playlists;

- Hüsnü Şenlendirici, with his releases and his playlists;

- Naseer Shamma, with his releases and his playlists; and

- Ross Daly, with his playlists.

In his Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25, “Classical” (1917) (approx. 14-19') (list of recorded performances), Sergey Prokofiev embraces the techniques of the “Classical Symphony”, which is the title he gave to this work. In this series of four short movements, in the highly resolved key of D major, he expresses a relaxed openness. “At a young age, Sergei Prokofiev was condemned as avant-garde and his music was perceived as difficult to understand. It is intriguing, then, that one of his most famous works Symphony No. 1 looks back to the older style of Haydn and is known by the nickname 'Classical.'” “Prokofiev was twenty-six when he composed his First Symphony, chiefly on holiday in the countryside.” “Shortly after his 26th birthday in April, he determined to find ‘some green spot where I could both work and walk’ during the summer months. He settled on an idyllic farm just outside the capital. ‘The main advantage,’ he explained, ‘was that the farm would provide delicious and wholesome food, whereas most dacha-dwellers [a dacha is a kind of small summer house in the countryside] from Petrograd were finding it literally hard to find anything at all to eat.’ It was in this island of tranquility that he would compose one of his best-loved works, his ‘Classical’ Symphony.” “The joke . . . was that the young iconoclast, who had earlier created an uproar with his Second Piano Concerto . . . should suddenly exchange revolutionary helmet and battle fatigues for periwig and knee-breeches to evoke the elegance of the Classical era.” Top recorded performances are conducted by Fricsay in 1954, Monteux in 1958, Rozhdestvensky in the 1960s, Ormandy in 1971, Ashkenazy in 1975, Celibidache in 1988, Neeme Järvi in 2005 ***, Gergiev in 2006, Silvestri in 2010, and Jordan in 2017.

Wilhelm Furtwängler, Symphony No. 2 in E Minor (1947) (approx. 80-83') (list of recorded performances), offers a rougher-edged view of spiritual retreat. He composed this, his most famous symphony, as a response to World War II and its many accompanying atrocities. “Wilhelm Furtwängler was always a stranger in this world. He was someone who went his own way and stood apart from the others: he could not be pigeonholed in any one category . . .” “Furtwängler was Hitler’s favorite conductor, and the Philharmonic’s wartime concerts were taped, according to minutes from a meeting with Joseph Goebbels, 'in accordance with the Führer’s wish.'” “Completed partly in exile, and partly under the cloud of a war crimes tribunal, which subsequently exonerated Furtwängler of complicity with the Nazis, the work does little to suggest the torment of a composer living through one of the most difficult periods of his life. True, there are moments of defiance – such as the closing pages of both the assai moderato and the adagio – but these are isolated moments in a work which is largely a personal spiritual testimony.” Generally not a peaceful, calm or restful work, this symphony illustrates a spiritual retreat for a troubled soul trying to create inner peace. Best recorded performances are conducted by Furtwängler in 1953, Jochum in 1954, and Barenboim in 2001.

Other compositions:

- Luis de Narvaéz, “Los seys libros del Delphin de musica” (music for vihuela, 16th century)

- Benjamin Britten, Holiday Diary, Op. 5 (1934) (approx. 17’) (list of recorded performances), “evokes the experience of an English seaside holiday: funfairs, still nights, and bracing dips into the sea.”

Albums:

- George Winston, “Summer” (1990) (59’): evocations of summer; and “Autumn” (1979) (46’): “A beautiful recording for solo piano, Autumn finds Winston developing simple melodic motifs with studied left-hand underpinning, on hypnotic pieces like ‘Woods’, which moves from a brisk rhythmic figure to rubato minor-key runs. Leaving pauses and breaths in all the right places, Winston suggests the play of color and light, the comfortable melancholy, and the encroaching slow-down that characterizes the fall season.”

- Brian Eno, “Thursday Afternoon” (1984) (61’) “weaves together a masterpiece of light and shade that is engaging as both: a musical score to the everyday and a stand alone listening experience. This is music that is indeed ‘minimal’ in the purest justification of the word, music that is an absolute distillation of the tiniest details and nuisances.”

- Paul Jones, “Let’s Get Tropical” (2019) (52’): “The whimsical title of saxophonist and composer Paul Jones’ eight-song quartet date — graphically illustrated by the leader’s sunny smile, flashy Hawaiian shirt and a backdrop of palm trees — suggests a frothy, fun-filled soundtrack for sipping mai tais on the beach . . .”

- Lars Danielsson Libretto, “Cloudland” (2021) (48’): “This is an album that feels distinctly Scandinavian, but is given breadth and depth through its global melting pot of influences. The quality and maturity of the playing on display underpin Danielsson’s prioritisation of melody – never trite, never saccharine – with every detail rendered exquisitely.”

- Harris Eisenstadt, “September Trio” (2011) (49’): “. . . armed with an equally prominent support system, Eisenstadt charts the mood or biorhythms of September, 2010, capturing and propagating a broad plane of sentiment, executed at either slow or medium-tempo processions.”

- Kim Myhr & Australian Art Orchestra, “Vesper” (2020) (56’) “brims with evocations, like the half-remembered smells of childhood. The title of the opening I caught a glimpse of the sea through the leafy boughs of the pines prepares you for the dreaminess . . .”

- The Sofia Goodman Group, “Secrets of the Shore” (2023) (54’): “Goodman wrote or co-wrote the ten numbers, each of which is designed to induce in the listener's mind some aspect of water, from placid to turbulent, gentle to intense.”

- Omri Mor & Yosef-Gutman Levitt, “Melodies of Light” (2023) (53’): “It is quite rare in a culture and society driven by autocrats, hits, likes, blogs and podcasts, that recordings as ethereal, yet born of the ageless earth, as Melodies of Light come around to release us from the daily ugly. Spontaneous music of this hypnotic, mysterious beauty and elusive grace give us pause to reflect on where we are, individually and collectively, and to seek a better way.”

- Rosemary Tuck, “Albert Ketèlbey: A Dream Picture” (2021) (55’): “Ketèlbey’s piano music evokes a totally different world, one of childhoods where it was always summer, and the sun never stopped shining.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Paul Simon, “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” (lyrics)

- Led Zeppelin, “Stairway to Heaven” (lyrics)

- Enya, “Orinoco Flow” (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), “Nachtgesang” (Night Song), D. 314 (1815) (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), “Die Einsiedelei” (The Hermitage), D. 393 (1816) (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert, “Das Einsiedelei” (The Hermitage), D. 563 (lyrics): a man wishes he could take refuge.

- Franz Joseph Haydn (composer), “The Mermaid’s Song”, Hob. XXVIa:25 (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Norman Rockwell, Vacation Boy Riding a Goose (1943)

- Boris Kustodiev, Summer (1922)

- Frederic Edwin Church, Mount Katahdin from Millinocket Camp (1895)

- Konstantin Korovin, In a Summer Cottage (1895)

- Ivan Shishkin, Summer Day (1891)

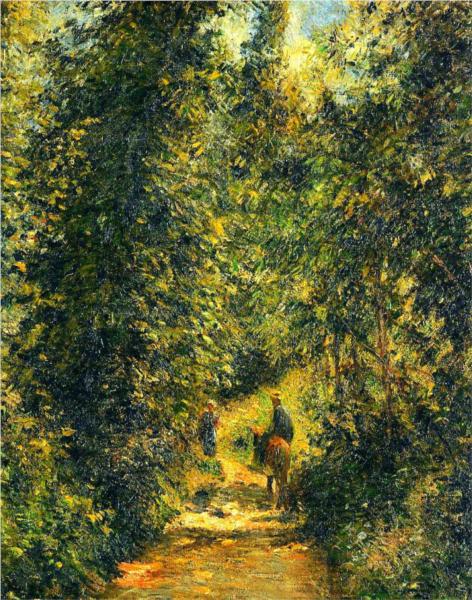

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Summer Landscape (1875)

- David Burliuk, Summer Gardens near the House

- John Constable, Helmingham Dell