Intellectually, before we can be reasonable, we must be rational.

- Five percent of the people think; ten percent of the people think they think; and the other eighty-five percent would rather die than think. [Widely attributed to Thomas A. Edison.]

Rationality is a predicate to reason, which is the level-two intellectual virtue in our relations to the material world. It is the rudimentary application of reason.

*******

“Those other people just don’t know how to think straight.” This tragically common refrain more often reflects as much as or more about the speaker than about the irrational hordes “out there”.

At its core, irrationality reflects desire: the desire to conform the world to what we wish and believe instead of vice versa (unchecked ego), to know even when we do not know (unhealthy intolerance for uncertainty), and to be right (lack of self-awareness). In recent decades, these subjects have been scientifically studied, resulting in a substantial body of knowledge about what rationality and irrationality are, their genesis and their implications the individuals and for communities and the world.

Being rational requires us to check our egos, and conform our thinking to reality instead of demanding and expecting reality to conform itself to our wishes and beliefs. An important element of rationality is logic, which is independent of what we believe or wish to believe. Another element is thinking critically not only about what others believe but about what we believe.

Rationality demands a tolerance for uncertainty. Our lives are shrouded in uncertainty. Failing to recognize that, and live and think accordingly, is a certain path to irrationality. Historically, leading figures from Aristotle to Piaget presented rationality as a function of logic, without accounting for uncertainty. “Bayesian Rationality argues that rationality is defined instead by the ability to reason about uncertainty. Although people are typically poor at numerical reasoning about probability, human thought is sensitive to subtle patterns of qualitative Bayesian, probabilistic reasoning.” This requires us to go beyond “pure logic” or “pure reason”, and understand not only that the material world is full of uncertainty but also that we and our fellow humans are complex mixtures of needs, wants, emotions and thoughts. Rationality requires us humans to evaluate probably risks and rewards. At one end of the spectrum are infants and also teenagers whose willingness to take unwise risks can lead to “drug use, illegal activity, and physical harm”. At the other end of the spectrum are seemingly responsible enterprises like business. At both ends, arguably, are whistleblowers, whose behaviors often are both rational and irrational simultaneously.

It requires a healthy degree of self-awareness. This is more than a philosophical construct alone. “Metacognition comprises both the ability to be aware of one’s cognitive processes (metacognitive knowledge) and to regulate them (metacognitive control). Research in educational sciences has amassed a large body of evidence on the importance of metacognition in learning and academic achievement. More recently, metacognition has been studied from experimental and cognitive neuroscience perspectives. This research has started to identify brain regions that encode metacognitive processes.” Lieder and Griffiths argue that “people gradually learn to make increasingly more rational use of fallible heuristics. This perspective reconciles the 2 poles of the debate about human rationality by integrating heuristics and biases with learning and rationality.” “Individuals with higher metacognitive insight into interpretation of evidence are less likely to polarize”.

On a wide range of critical public issues, such as climate change, belief about how much we think we know appears to shape public policy. However: “Confirmation bias is adaptive when coupled with efficient metacognition”. Based on their study of subjective cognitive decline, Jenkins, et. al., conclude: “Dysfunctional cognitive control at a meta-level may impact someone’s ability to rationally identify cognitive changes, increase worry about cognitive changes, and allow such changes to impact their lives more than those with superior metacognitive control.” Based on data from their research, DaSilveira, et. al., suggest “that while self-reflection measures tend to tap into past experiences and judged concepts that were already processed by the participants’ inner speech and thoughts, the Awareness measure derived from Mindfulness Scale seems to be related to a construct associated with present experiences in which one is aware of without any further judgment or logical/rational symbolization.” Borrell-Carrió and Epstein have proposed “a so-called rational-emotive model (for clinical medical practice) that emphasizes 2 factors in error causation: (1) difficulty in reframing the first hypothesis that goes to the physician’s mind in an automatic way, and (2) premature closure of the clinical act to avoid confronting inconsistencies, low-level decision rules, and emotions.”

Real

True Narratives

- Carla Power, Home, Land, Security: Deradicalization and the Journey Back from Extremism (One World, 2021): “Through interviews with the family members of Westerners who joined ISIS, Power humanizes militant jihadists and offers insights into the forces that push people toward extremism.”

From the dark side:

- Justin E.H. Smith, Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason (Princeton University Press, 2019): “This is the history of rationality, and therefore also of the irrationality that twins it: exaltation of reason, and a desire to eradicate its opposite; the inevitable endurance of irrationality in human life, even, and perhaps especially — or at least especially troublingly — in the movements that set themselves up to eliminate irrationality; and, finally, the descent into irrational self-immolation of the very currents of thought and of social organization that had set themselves up as bulwarks against irrationality.”

- Mia Bloom and Sophia Moskalenko, Pastels and Pedophiles: Inside the Mind of QAnon (Redwood Press, 2021): “Adherents believe Donald J. Trump is battling the cabal, which, depending on whom you ask, may or may not comprise members of a reptilian alien race disguised as humans.”

- Charles J. Skyes, How the Right Lost Its Mind (St. Martin’s Press, 2017): “A conservative talk-radio host who found himself alienated from his audience and many of his comrades by the rise of Trump, Sykes reexamines his beliefs, and finds himself with more questions than answers.” Apparently, he has figured out (part of) what has been obvious to many people for decades.

- Susan Wels, An Assassin in Utopia: The True Story of a Nineteenth-Century Sex Cult and a President’s Murder (Pegasus Crime, 2023), “links President Garfield’s killer to the atmosphere of free love and religious fervor that gripped Oneida, N.Y., in the late 1800s.”

Still on the dark side, here are some histories of conspiracy theories:

- Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1964).

- Anna Merlan, Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power (Metropolitan Books, 2019): “Throughout the book, she reports from gatherings of people whose beliefs are both extreme and false.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

Texts on rationality:

- Steven Pinker, Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters (Viking, 2021): “Probability and statistics now loom large in both straight and crooked thinking, but logic manuals generally offered only small bites of such fare. The main courses were usually a parade of fallacies, explained in words, plus formal deductive logic (which strips inferences to their skeletons, such as “Some A are B; therefore some B are A”). Pinker has now added comprehensive lessons on statistical significance, how to update your beliefs in the light of fresh data, how to calculate risks and rewards in decision-making and more.”

- Gerd Gigerenzer, Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty (Oxford University Press, 2008): “The book deals with two complementary modes of thinking of the human mind: heuristic and statistical. Bounded rationality by heuristic thinking is the key to understand how real people make decisions when time and information are limited. Statistical thinking is the key to describe the limits of human inference under uncertainty.”

- Gerd Gigerenzer and Richard Selten, eds., Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox (The MIT Press, 2001): “This book promotes bounded rationality as the key to understanding how real people make decisions. Using the concept of an ‘adaptive toolbox,’ a repertoire of fast and frugal rules for decision making under uncertainty, it attempts to impose more order and coherence on the idea of bounded rationality.”

- Gerd Gigerenzer, Adaptive Thinking: Rationality in the Real World (Oxford University Press, 2000): “Gerd Gigerenzer is a man with a mission, and a mission that has some point to it. He wants to show that people are rational decision makers, most of the time.”

- Keith E. Stanovich, What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought (Yale University Press, 2009): “Stanovich shows that IQ tests (or their proxies, such as the SAT) are radically incomplete as measures of cognitive functioning. They fail to assess traits that most people associate with ‘good thinking,’ skills such as judgment and decision making.”

- Keith E. Stanovich, Rationality and the Reflective Mind (Oxford University Press, 2010): “. . . the author's characterization of his opponents does not seem completely fair or charitable. It is unclear whether Panglossians deny the existence of individual differences or cannot accommodate them. Moreover, there seem to be more arrows in the Panglossians’ quiver than the ones the author mentions. In addition, his main theoretical points are not entirely clear: it is controversial whether data on individual differences provide clues for arbitrating between normative systems, and whether those data are enough to make the case for a tripartite model of the mind. As a result, critics may still doubt that Stanovich has successfully combined his different research projects, and we may conclude that this book has not achieved his grand ambition of resolving the rationality debate.”

- Keith E. Stanovich, Richard F. West and Maggie E. Toplak, The Rationality Quotient: Toward a Test of Rational Thinking (The MIT Press, 2016): “While there is scant evidence that any sort of “brain training” has any real-world impact on intelligence, it may well be possible to train people to be more rational in their decision making.”

- Robert J. Sternberg, Why Smart People Can Be So Stupid (Yale University Press, 2002): “While many millions of dollars are spent each year on intelligence research and testing to determine who has the ability to succeed, next to nothing is spent to determine who will make use of their intelligence and not squander it by behaving stupidly. Why Smart People Can Be So Stupid focuses on the neglected side of this discussion, reviewing the full range of theory and research on stupid behavior and analyzing what it tells us about how people can avoid stupidity and its devastating consequences.”

- Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic and Amos Tversky, eds., Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (Cambridge University Press, 1982): “How do people assess the probability of an uncertain event or the value of an uncertain quantity? This article shows that people rely on a limited number of heuristic principles which reduce the complex tasks of assessing probabilities and predicting values to simpler judgmental operations. In general, these heuristics are quite useful, but sometimes they lead to severe and systematic errors. ” (The quotation is from a 1974 article by two of the editors.)

- Julia Galef, The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t (Portfolio, 2021): she describes the scout mindset as the motivation to see things as they are, not as you wish they were.

From the dark side:

- Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions (Harper Perennial, 2010).

- Ori Brafman and Rom Brafman, Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behavior (Crown Business, 2008).

- Jennifer L. Eberhardt, Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do (Viking, 2019): “If our brains didn’t apply categorical knowledge, usually before we’ve had a chance to consciously reflect, we’d experience everything as if for the first time. . . . The problem is that when we live in a society divided by race, gender, class or some other category, our brains learn those social groupings, too, and apply them to order our perceptual field, even when they are more arbitrary than real, even when the “knowledge” attached is a pernicious stereotype and even if we’re committed to equality.”

In many ways, irrationality rules the world. Theism is a prime example. Not all religion is theistic. Yet theism’s dominance in the field of religion is so complete that most people do not bother to add the qualifier “theistic”. Here are some books on the irrationality of theistic religion.

- Jerry A. Coyne, Faith Versus Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible (Viking, 2015): “He examines the varieties of accommodationism and explains why each of them fails. Finally, he demonstrates why the conflict between faith and facts matters, highlighting significant impacts of religiously sourced “knowledge”—from religiously motivated child abuse to the running controversy over human-caused climate change.”

- Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006): “What Dawkins brings to this approach is a couple of fresh arguments — no mean achievement, considering how thoroughly these issues have been debated over the centuries — and a great deal of passion.”

A related subject, also being extensively researched, is that of the rise, persistence and sometimes usefulness of conspiracy theories.

- Jerry E. Uscinski, Conspiracy Theories: A Primer (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020).

- Jerry E. Uscinski, ed., Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them (Oxford University Press, 2018): “a collection that brings together contributors to offer a wide-ranging take on conspiracy theories, examining them as historical phenomena, psychological quirks, expressions of power relations and political instruments.”

- Jerry E. Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent, American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford Univsity Press, 2014): “the authors do not look down upon conspiracy theorists. They believe that, to a certain extent, conspiracy theorizing is a normal phenomenon and can tell us a lot about politics and society. In the end, many great moments in American history had their own conspiracy theories. Before and during the Civil War the abolitionists accused the Slave Power of the South, during the Progressive movement of the early twentieth century Progressives charged the robber barons of conspiring against the common American, and the American revolutionists of the eighteenth century revolted against the conspiracies of the British crown. Of course, slavery, the concentration of trusts and the British imperial dominion were real facts, but it is also true that their opponents frequently used conspiratorial rhetoric in order to mobilize supporters.”

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

From the dark side:

- Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief: Prominent among the several themes in this film is the breathtaking irrationality of scientology, both in its founding ideas and in its practices.

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Lewis Carroll (real name Charles Lutwidge Dodson) explored irrationality in his novels, stories and poems. “The Alice books are often said to be significant because, if you read them, you’ll notice they are full of complicated, seemingly mature thought processes and reasoning. Many experts think Lewis Carroll did this purposely to illustrate that children are capable of complicated thoughts and reasoning as well, sometimes even more so than adults.”

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865): “The story centres on Alice, a young girl who falls asleep in a meadow and dreams that she follows the White Rabbit down a rabbit hole. She has many wondrous, often bizarre adventures with thoroughly illogical and very strange creatures, often changing size unexpectedly . . .” “The underlying story, the one about a girl maturing away from home in what seems to be a world ruled by chaos and nonsense, is quite a frightening one. All the time, Alice finds herself confronted in different situations involving various different and curious animals being all alone. She hasn’t got any help at all from home or the world outside of Wonderland.”

- Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1871): Alice enters an upside-down, inside-out world, “as she moves through a mirror into another unreal world of illogical behaviour, this one dominated by chessboards and chess pieces.”

Other novels, from the dark side:

- Margaret Meyer, The Witching Tide: A Novel (Scribner, 2023) “evokes the climate of fear and accusation that grips a town with the arrival of a 'witchfinder.'”

Poetry

Lewis Carroll, “The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony in Eight Fits” (1876): “After crossing the sea guided by the Bellman's map of the Ocean—a blank sheet of paper—the hunting party arrive in a strange land. The Baker recalls that his uncle once warned him that, though catching Snarks is all well and good, you must be careful; for, if your Snark is a Boojum, then you will softly and suddenly vanish away, and never be met with again.” “Carroll denied that he meant anything in particular – the poem was all nonsense – but that did not stop people asking him, and it inspired others to give it their own meaning. To some extent, the poem is about the relationships that emerge among the crew, and the interaction between this motley bunch of characters. All behave in odd ways, some have close-shaves, and one completely vanishes – caught by a Boojum.”

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Franz Joseph Haydn was a composer of the Enlightenment, as reflected in his symphonies. Most of them are straightforward works. Several of his late symphonies are announced with mundane themes, such as “Clock,” “Drumroll,” “Military” and “Surprise,” as well as representations of a “Bear” and “Hen,” and homages to “Oxford” and “London.” These are mainly from the Paris symphonies (Nos. 82-87) and the London symphonies (No. 93-104).

- Symphony No. 82 in C Major, Hob. I:82, “L’Ours” (The Bear) (1786) (approx. 23-26’): “It is the finale that gave this symphony its nickname. The droning bass and country carnival atmosphere suggested dancing bears to the French.” Top recordings are conducted by Bernstein in 1962, Karajan in 1981, Colin Davis in 1988, and Sigiswald Kuijken in 1989.

- Symphony No. 83 in G Minor, Hob. I:83, “Le Poule” (The Hen) (1785) (approx. 21-26’): “Opera taught Haydn to avoid the violence of disrupting and tearing the musical fabric with emotional outbursts for mere effect, and to integrate these distinguishable dramatic events within the frame of symmetrically balanced, closed forms reminiscent of classical comedy and tragedy. The inner tension of individual conflicting musical events, and the resolution of that conflict within the parameter of controlled harmonic polarities, gave to his instrumental music the structure of narrative: dramatic performance outside the context of the theater.” Top recordings are conducted by Bernstein in 1962, Karajan in 1981, and Sigiswald Kuijken in 1989.

- Symphony No. 92 in G Major, Hob. I:92, “Oxford” (1789) (approx. 24-28’): “The symphony is called the 'Oxford' because Haydn reportedly conducted it at a ceremony in 1791 in which he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University. The name is something of a misnomer, because the symphony was actually written earlier for performance in Paris.” Top recordings are conducted by Szell in 1962, Böhm in 1974, and Leitner in 2006.

- Symphony No. 94 in G Major, Hob. I:94, “Surprise” (1791) (approx. 22-25’): “Perhaps the least well-considered title is ‘Surprise,’ appended by English audiences to the Symphony No. 94 simply because of the single loud chord occurring at the end of the quiet second sentence of the Andante movement.” Top recordings are conducted by Toscanini in 1953, Szell in 1968, and Bernstein in 1973.

- Symphony No. 100 in G Major, Hob. I:100, “Military” (1794) (approx. 23-26’): “In addition to the standard pairs of winds, horns, and trumpets as well as strings and timpani, the orchestra included a battery of ‘Turkish’ percussion (triangle, cymbals, and bass drum), for which there was a great vogue in late-18th-century European music. The Turks had ceased to be a threat to Europe when the Austrians and Poles defeated them outside of Vienna in 1683; a century on, Europeans could view their once-threatening enemies in a different light.” Top recordings are conducted by Beecham in 1958, Doráti in 1960, and Bernstein in 1976.

- Symphony No. 101 in D Major, Hob. I:101, “Clock” (1794) (approx. 26-28’): “The Symphony No. 101 is, like the others in the set, formally inventive; something unusual happens in every movement. The nick-name, which describes the ostinato accompaniment of the second movement, apparently comes from a 1798 Vienna transcription of the movement for piano, where it was called 'Rondo: The Clock.'” Top recordings are conducted by Monteux in 1959, Abbbado in 1988, Minkowski in 2009, and Paavo Järvi in 2019.

- Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, Hob. I:103, “Drumroll” (1795) (approx. 28-33’): “The subtitle . . . ‘Drum Roll,’ is derived from the timpani cadenza that opens the first movement.” Top recordings are conducted by Beecham in 1959, Doráti in 1959, Bernstein in 1975, and Weil in 2015.

- Symphony No. 104 in D Major, Hob. I:104, “London” (1795) (approx. 24-29’): Top recordings are conducted by Szell in 1954, Beecham in 1959, Bernstein in 1969, and Weil in 2015.

Lewis Carroll explored a world of irrationality through the eyes of his iconic character Alice. His Alice stories provide fertile ground for musical composition.

- David del Tredici, Final Alice (1976) (approx. 59’): “Like Gustav Mahler, whose obsession with a collection of German folk poetry called Das Knaben Wunderhorn led him to compose a series of treasured epic symphonies and song cycles, Del Tredici found an equally nurturing and seemingly inexhaustible musical universe in Carroll’s satiric word-play and idiosyncratic proto-surrealism . . .”

- David del Tredici, Child Alice , for soprano(s) (amplified) and orchestra (1977-1981) (approx. 230-235’): “Despite the work’s epic length, there are only two themes: Part I introduces a soaring, bel canto-tinged melody, and Part II adds a skipping, British-sounding tune . . .”

- Giampoalo Testoni, Alice (1993) (approx. 170-175’), an opera

- Richard Addinsell, Alice in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass (1947) (approx. 56’)

- John Barry, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1972) (42’) soundtrack

- Richard Birchall, “Alice in Wonderland” (2018) (64’) album

- Derek Bourgeois, “Jabberwocky”: an extravaganza for baritone solo, chorus & orchestra (1963) (approx. 58’)

- Joby Talbot, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” album (2013) (67’)

- Irving G. Fine, Hour-Glass and Three Choruses from Alice in Wonderland (1942) (approx. 32’)

- Daniele Gasparini, Through the Looking-Glass, for orchestra (1998) (approx. 13’)

- Arne Nordheim, The Hunting of the Snark and The Return of the Snark, for solo trombone (approx. 23’)

- J. Deems Taylor, Through the Looking-Glass suite, Op. 12 (1923) (approx. 30’)

Jazz and other popular artists, too, have taken up the Alice story, and created these albums:

- Ravi Shankar, “Alice in Wonderland” (1966) (11’), soundtrack

- Donovan, “The Hurdy Gurdy Man” (1968) (34’)

- Chick Corea, “The Mad Hatter” (1977) (50’)

- Tom Waits, “Alice” (1992) (48’)

- Clive Nolan & Oliver Wakeman, “Jabberwocky” (1998) (54’)

- Ibrahim Maaloof, “Au pays d’Alice” (2014) (60’)

- Meinhard, “Beyond Wonderland” (2013) (56’); “Wasteland Wonderland” (2022) (54’)

- John Abercrombie, “Alice in Wonderland” (2019) (10’) track

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Meshuggah, “Rational Gaze” (lyrics)

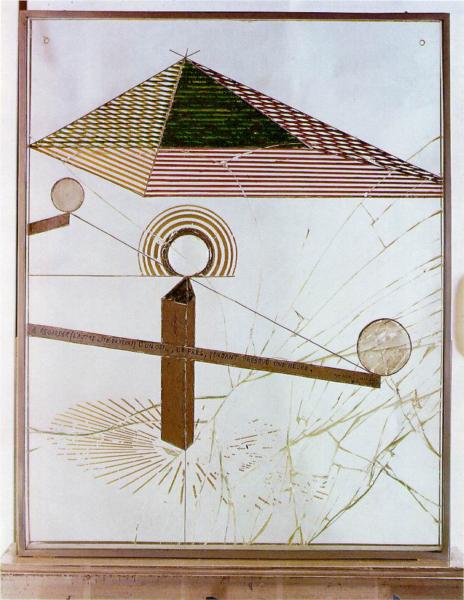

Visual Arts

- Nurdan Karasu Gokce, ataraksia I

- Lee Krasner, Seed No. 5 (1969)