After we have learned to think, we can act rationally and purposefully. Our development has put us in a position to affect our lives, the lives of others and the course of the world. We can see this as a burden, or as an invitation to the grand dance of human life.

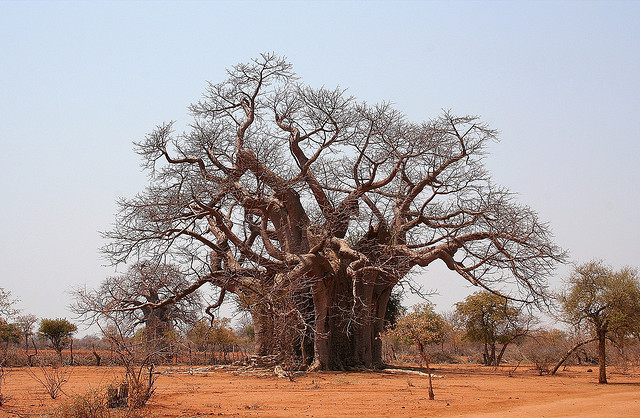

Come with me, to the Baobab tree,

To the Baobab tree, where eyes will shine,

And hearts will leap

And feet will dance

And hands will touch

In one-two time.

Come with me, to the Baobab tree,

To the Baobab tree, where tears will dry,

And lips will sing

And hearts will breathe

And feet will dance

In one-two time.

[“The Baobab Tree,” Julie Redstone]

- It’s lovely to live on a raft. We had the sky up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on our backs and look up at them, and discuss about whether they was made or only just happened . . . [Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), Chapter 19.]

- A river rises in Eden to water the garden; beyond there it divides and becomes four branches. [The Bible, Genesis 2:10.]

Action is the culmination of ethics, so in Ethical Culture many of us say “deed over creed.” I have always thought that too general a statement, literally interpreted. It is true that words without actions are empty; however, actions without thoughts are reckless, and actions uninformed by emotion are rudderless. To employ a Christian metaphor, the Father principle (thought) and the Mother principle (emotion) produce the Son (action), who comes into the world, dirties his hands and builds a life. You need not see it that way but you can. The religious, spiritual, ethical and moral life at its best is not a struggle for dominance of one domain or point of view but a constant striving to bind them together into a coherent whole. Felix Adler was reacting to the unsubstantiated elements in religion, emphasizing that Ethical Culture was a religion of ethical responsibility and action.

Brain development makes it possible for us to build roads, nurture others and create civilization. By adulthood, the necessary foundations are in place. We decide what to make of them.

Life-in-Being invites us to act purposefully. Most of us work or go to school, have responsibilities and spend much of our time serving others. Even those who live a meditative life must practice their teachings, not to mention eat and do those things necessary to survival. Our actions are the means by which we give back some measure of good and experience it for ourselves.

We choose to see life as an invitation. This is a matter of focus, not exclusion. We endorse ethical/moral commitments, rules and obligations of conduct. However, life is what we make of it. For those of us fortunate enough to be able to consider it, a great bounty lays before us. We are invited to the feast and the dance of life. What we make of it, is largely up to us; all the more if we pull together.

Real

True Narratives

The deaf-blind person may be plunged and replunged like Schiller's diver into seas of the unknown. But, unlike the doomed hero, he returns triumphant, grasping the priceless truth that his mind is not crippled, not limited to the infirmity of his senses. The world of the eye and the ear becomes to him a subject of fateful interest. He seizes every word of sight and hearing because his sensations compel it. Light and colour, of which he has no tactual evidence, he studies fearlessly, believing that all humanly knowable truth is open to him. He is in a position similar to that of the astronomer who, firm, patient, watches a star night after night for many years and feels rewarded if he discovers a single fact about it. The man deaf-blind to ordinary outward things, and the man deaf-blind to the immeasurable universe, are both limited by time and space; but they have made a compact to wring service from their limitations. [Helen Keller, The World I Live In (1907), chapter VIII, “The Five-Sensed World”.]

Ballet is one highly sophisticated form of action, along with other forms of dance.

- Jennifer Homans, Apollo’s Angels:A History of Ballet (Random House, 2010).

- Henry Alford, And Then We Danced: A Voyage Into the Groove (Simon & Schuster, 2018).

- Laura Jacobs, Celestial Bodies: How to Look at Ballet (Basic Books, 2018).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Not technical but worthwhile anyway:

- Oriah Mountain Dreamer, The Dance: Moving To the Rhythms of Your True Self (HarperCollins, 2001): “Her central theme is that who we are is enough (loving enough, compassionate enough) and that only fear prevents us from accepting this liberating truth. Another recurring theme is the importance of learning to hold and keep others in our hearts in order to dissolve the divisive us-and-them dichotomy that deadens empathy.”

- Oriah Mountain Dreamer, The Invitation (HarperCollins, 1999): “. . . the author speaks from the heart, reflecting on everything from desire to betrayal and offering practical - and often surprising - suggestions for how to live the ecstasy of everyday life, learn to recognise true beauty in ourselves and the world around us, and how to find the sustenance that our spirit longs for.”

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Novels:

- Winner of the 1994 Newberry Medal, Lois Lowry’s The Giver (Laurel Leaf), 2002, tells of a utopian community that has purchased material comfort at the price of its humanity. As the child protagonist learns after being selected to be the community's Receiver of Memories, being human without enduring suffering is impossible.

- Jess Walter, Beautiful Ruins: A Novel (HarperCollins Publishers, 2012): “. . . on how we live now, and . . . on how we lived then and now, here and there.”

Novels, from the tragic side:

- Niall Williams, Time of the Child: A Novel (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024): “Dr. Jack Troy and his eldest daughter, Ronnie, are spending their days much as they have since the death of Jack’s wife and Ronnie’s mother, Regina: They go to Mass; they go to dinner . . . But they are also holding core truths from each other — in Jack’s case, his unspoken feelings for the now-dead Annie Mooney, with whom he might have found a second chance at love if only he’d acted soon enough . . . Since Annie’s death, Jack has become more and more melancholy, and at a pivotal Mass on the first Sunday of Advent, he realizes ‘he had lost his love of the world.' . . . He continues his work in the small town, but with a sense of obligation, not joy.”

Poetry

One's-self I sing, a simple separate person,

Yet utter the word Democratic, the word En-Masse.

Of physiology from top to toe I sing,

Not physiognomy alone nor brain alone is worthy for the Muse, I say the Form complete is worthier far,

The Female equally with the Male I sing.

Of Life immense in passion, pulse, and power,

Cheerful, for freest action form'd under the laws divine,

The Modern Man I sing.

[Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1891-92), Book I: Inscriptions, “One’s Self I Sing”.]

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Richard Strauss composed his famous tone poem, “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” (Also Sprach Zarathustra), Op. 30, TrV 176 (1896) (approx. 31-36’), after Nietzsche’s philosophical novel Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book For All and One (1885). Nietzsche’s novel creates a story about the Zoroastrian god in which he “brings Zarathustra back to atone for his mistakes by teaching a new teaching”. We can hear Strauss applying this invitation to life as he understood and experienced it. He takes us from the creation to contemporary life, the Romantic era at the time of the composition. He begins with a musical creation story (0:12), which he follows with one of the most sweepingly romantic sequences in music (2:57): the effect is like juxtaposing Michelangelo’s famous “Creation of Adam” detail from the Sistine chapel with Auguste Rodin's "The Kiss". In this music is all our desire, love and passion (4:38). Then a note of doubt sounds (5:33), followed by a lightening of tone, as if rainclouds had parted, revealing the blue sky (5:56). The mood alternates for a time, invoking the interplay between optimism, doubt and love. Misfortune strikes (7:52) but the protagonist perseveres (8:28), determined to enjoy life (9:00). Individual voices suggest the twists and turns that are part of life. The gentle theme of life has an ominous undertone (2:47). Strauss, who was renowned for his prodigious ego, probably was writing to present his inner life experience in music. The hero faces another challenge, which he meets playfully (5:14) and with humor (6:09). Another challenge proves more daunting (6:37). The creation theme returns, suggesting that our hero is confronting existential questions (8:19). Never one to spare on drama, Strauss continues in an ominous tone, interspersed with other motifs but in the end, of course, he is more than equal to every challenge (1:36). The opening theme becomes commonplace (2:52) and then the composition begins to hint of a dance (3:26); the romantic theme then reappears in the same form (4:06). By now the hero is playing at life as a fine concertmaster plays his violin (4:56). Strauss seems to have composed his dramatic conception of human life. He concludes the work with a statement of mature serenity, laced with an ominous undertone (6:21), suggesting that challenges lay ahead. Top recorded performances were conducted by Koussevitzky in 1935, Reiner in 1954, Mitropoulos in 1958, Kempe in 1971, Karajan in 1973, Sinopoli in 1987, and Nelsons in 2015. Strauss conducted the work in 1944. Live video-recored performances were conducted by Jansons, Măcelaru, and Dudamel.

- Prelude (Sonnenaufgang) (Introduction, or Sunrise) – the famous theme, evoking a grand beginning, perhaps the dawn of life or the beginning of the world;

- Von den Hinterweltlern (Of the Backworldsmen) – from the primeval soup, straightaway into 19th-century romanticism – an epic love theme, evoking sunshine and bliss;

- Von der großen Sehnsucht (Of the Great Longing) – from an ideal into real life – the romantic theme persists but encounter adversity;

- Von den Freuden und Leidenschaften (Of Joys and Passions) – tragedy has struck but we persevere;

- Das Grablied (The Song of the Grave) – we reflect and ask, “What next?” Days turn into years;

- Von der Wissenschaft (Of Science and Learning): A distant voice appears, ominously and almost inaudibly. As it becomes louder, sorrow comes into focus, underlain by bits of the romantic theme. A solo trumpet heralds a new beginning . . .

- Der Genesende (The Convalescent) . . . but a storm arises. The trumpet sounds to meet the challenge but circumstances overwhelm it. A motif from the grand opening theme re-appears. Voices compete – to survive, perhaps, or to thrive, maybe to dominate;

- Das Tanzlied - Das Nachtlied (The Dance Song – The Night Song): In the calm, a solo violin announces resilience and joy, joined by a trumpet. The romantic theme appears again, and this time it endures. The trombones restate the grand opening theme but now it is in the background. The people dance. Practical notes sound but they are no longer overwhelming. They have become parts of a happy life.

- Das Nachtwanderlied (Song of the Night Wanderer): bells and trumpets sound. Life’s struggles continue but peace and acceptance emerge. A mature romantic theme sounds in the strings, evoking a long-married couple reflecting on their lives together. Someone comforts them, perhaps their children (woodwinds). The end approaches and arrives.

Perhaps our oldest musical instrument, the drum invites us to act purposefully – to dance. “Initially used by our prehistoric ancestors just as a simple object that were hit by the stick, drums came into their modern form some 7 thousand years ago when the Neolithic cultures from China started discovering new uses for alligator skins.” “. . . music started with the most primitive percussion instruments, in times before first civilizations even existed.” “Even monkeys like to beat a rhythm by striking hollow trees, and the rhythmic beating of a mother's heart is the first, most familiar sound that a child hears in the womb.” Though drums are widely used in combination with instruments that are best known for pitch production, unaccompanied drumming best evokes music as an inducement to act.

- A primary exponent of this music was Babatunde Olatunji, who is widely credited with bringing African music to the West. His albums and live performances include “Drums of Passion” (1960) (40’), “Zungo” (1961) (41’), “Flaming Drums” (1962) (35’), “Dance to the Beat of My Drum” (1986) (53’), “Circle of Drums” (63’) (1995), “Love Drum Talk” (1997) (68’), Olatunji live at Starwood in 1997 (67’), and an African Drumming video (61’).

- The tabla is an essential instrument in Indian classical music. Its greatest exponent is Zakir Hussain. Here he is in a live performance in Calcutta (52’), and in another live performance (85’). Albums on which he is listed as the solo artist include “Selects” (2002) (62’), “Sambanhd” (1998) (69’), “Magical Moments of Rhythm” (1995) (61’), “Soundscapes – Music of the Deserts” (1992) (58’), “Zakir Hussain and The Rhythm Experience” (1991) (45’), and “Moment Records – A Collection - Volume 1” (1990) (76’). Other tabla masters include Akram Khan (72’) and Swapan Chaudhuri (66’).

- Steve Reich gave performances in the early 1970s, illustrating the art of “Drumming” (57’). His minimalist music is not limited to drumming but does focus on rhythms, and sounds. Here he is in live performance with Eighth Blackbird in 2011, with L'ensemble de percussion de l'Université de Moncton in 2017, and at Dekmantel Festival in 2017. His albums include “Steve Reich” (2020) (221’), “The Cave” (1995) (103’), and “Drumming” (live recording) (1971) (81’).

- Here are a few videos: from Mali, West African dancers with Bolokada, from Guinea, West Africa, and Dunaba dance party, Guinea, West Africa.

- Albums of drumming include Twins Seven Seven, “Nigerian Beat” album (72’); and “Sola Akingbola's Nigerian Beats” album (48’) (48’).

Other works illustrating life as an invitation:

- Gabriel Fauré, Masques et Bergamasques, Op. 112 (1919) (approx. 28-30’ [divertissement] or approx. 13-16’ [suite]), celebrates the fêtes galantes of the 18th century. The composer’s program read: “The story of Masques is very simple. The characters Harlequin, Gilles and Colombine, whose task is usually to amuse the aristocratic audience, take their turn at being spectators at a ‘fête galante’ on the island of Cythera. The lords and ladies, who as a rule applaud their efforts, now unwittingly provide them with entertainment by their coquettish behavior.” An excellent recording of the divertissement is by Plasson & Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse. Top recordings of the briefer suite are conducted by Ansermet in 1962, Marriner in 1981, Jordan in 1993, and Bolton in 2019.

- Paul Wranitzky (Pavel Vranický), Das Waldmädchen, ballet-pantomime (1796) (approx. 66’), is “. . . an archetypal tale of a girl out in the forest who encounters a Prince out hunting (we hear the hunting gestures and horns as early as the second number), Their love story forms the rest of the story, including a ball in the third act in which we find that our heroine is actually a Princess and her match with the Prince is complete! The music is as charming as the premise.”

Albums:

- Hubert Laws, “Morning Star” (2010) (36’): as the title suggests, sunrise invites us to begin the day.

- Katerina Brown, “Mirror” (2018) (49’), is music of longing and possibility.

- Trio Casals, “Moto Bello” (2018) (81’), “is a journey through individual experience, international scenes, and philosophical pondering. Each piece is an exploration of movement and of the beauty in all forms of motion—dissonant and jagged, soft and freely flowing, or standing tentatively between the two.”

- Paula Abdul, “Shut Up and Dance” (1990) (51’): “Paula’s role in bringing dance music to the late 80’s pop/rock charts was important . . .”

- Ramon Lopez, “Swinging with Doors” (2016) (47’): “Rhythms, harmonically rich and breathlessly original, spawn from classical, jazz and tribal traditions.”

- Ludovico Einaudi, “Like a Breath” (2023) (52’)

- Alina Bzhezhinska & Tony Kofi, “Altera Vita” (2024) (33’): “This ineffably beautiful and restorative disc succeeds resoundingly in its mission statement. This is, say the duo, to offer listeners something that 'guides us through the turbulence and discord' of what has become 'an era yearning for serenity, spirituality and peace.'”

- Natalie Wildgoose, “Come into the Garden” (2025) (17’): “She starts with a brief piano-led song, simply called Introduction. The notes seem to be going nowhere, but really, they are going everywhere all at once, falling like water, pooling in the dusty corners of the song. The melody is an impressionistic thing, like an idea of a dream committed to music.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

The Irish folk song “Wild Mountain Thyme” (lyrics) [perf. James Taylor] (“Will You Go, Lassie, Go”) [Manca Izmajlova] expressions an ideal [Sarah Calderwood] of daily living. These young singers remind us of what life can be, both in their singing and in their very presence.

Other songs:

- Rachel Caswell, “We’re All in the Dance” (lyrics)

- Tom Cochrane, “Life Is a Highway” (lyrics)

- Billie Eilish, "Come Out and Play" (lyrics)

- Franz Schubert (composer), “Der Schmetterling” (The Butterfly), Op. 71, No. 1, D. 633 (1819) (lyrics)