Forgiving is letting go of what binds us to the past in unhealthy ways.

- The Amish made it look simple. Ten of their precious little girls had been shot . . . . (They) enfolded their grief within their normal circle of prayer and daily communion. They didn’t speak out. They looked within. They did it together. [Kenneth Briggs, The Power of Forgiveness: Based on a Film by Martin Doblmeier (Fortress Press, 2008), p. 9.]

- Forgiveness is both an art and a science. As an art, it deals with the fundamental questions of our age. It describes how we deal with offenses and transgressions personally and socially. . . Forgiveness also is now a science. [Everett L. Worthington]

- Forgiveness is the needle that knows how to mend. [Jewel, “Under the Water.”]

- When you release the wrongdoer from the wrong, you cut a malignant tumor out of your inner life. You set a prisoner free, but you discover that the real prisoner was yourself. [Lewis B. Smedes, Forgive and Forget: Healing the Hurts We Don’t Deserve (HarperCollins, 1984), p. 133.]

- As I walked out the door toward my freedom, I knew that if I did not leave all the anger, hatred and bitterness behind, I would still be in prison. [attributed to Nelson Mandela]

You can choose not to forgive someone, including yourself. If you do that, you will only carry around the excess weight of negative thoughts and feelings about something you wish had never happened.

To forgive is to wash anger and resentment away, and live as we might have done had the undesired events never happened, with one exception. Forgiving does not mean forgetting. It does not mean that we should trust someone who has disappointed or harmed us time after time. It only means that we will not let those things weigh on us as we move forward, and that we will not spend our time and energy thinking of ways to harm those who have harmed us.

Forgiveness is not completed simply by letting go and moving on. “True forgiveness goes a step further . . . offering something positive—empathy, compassion, understanding—toward the person who hurt you.”

There are two basic kinds of forgiveness. “Decisional forgiveness is a behavioral intention to resist an unforgiving stance and to respond differently toward a transgressor. Emotional forgiveness is the replacement of negative unforgiving emotions with positive other-oriented emotions. Emotional forgiveness involves psychophysiological changes, and it has more direct health and well-being consequences.” Emotional “(f)orgiveness is conceptualized as an emotional juxtaposition of positive emotions (i.e., empathy, sympathy, compassion, or love) against the negative emotions of unforgiveness.”

Forgiveness yields substantial health benefits. “. . . the act of forgiveness can reap huge rewards for your health, lowering the risk of heart attack; improving cholesterol levels and sleep; and reducing pain, blood pressure, and levels of anxiety, depression and stress. And research points to an increase in the forgiveness-health connection as you age.” Both state and trait forgiveness yield positive results in real time, and over time (state; trait).

Forgiveness is socially important. It is especially important in ongoing relationships, including romantic relationships.

In addition to forgiving others, we can forgive ourselves. Not doing so can impede us as much or more as not forgiving others.

Real

True Narratives

- Kenneth Briggs, The Power of Forgiveness: Based on a Film by Martin Doblmeier (Fortress Press, 2008)

- Donald W. Shriver, Jr., An Ethic for Enemies: Forgiveness in Politics (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Sarah Beckwith, Shakespeare and the Grammar of Forgiveness (Cornell University Press, 2011).

- Jennifer Berry Hawes, Grace Will Lead Us Home: The Charleston Church Massacre and the Hard, Inspiring Journey To Forgiveness (St. Martin’s Press, 2019): “. . . a Polk Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, offers a fuller, more complicated picture of the massacre and its aftermath.”

- Jeannie Vanasco, Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl: A Memoir (Tin House Books, 2019): “It’s about violence and forgiveness, about friendship and the unwanted title of victim, about digging deeper and deeper to seek answers — from yourself and from your bogeyman. But in this memoir, questions beget more questions, and few are sufficiently answered. Trauma cannot be tied with a tidy bow.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Glen Pettigrove & Robert Enright, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy and Psychology of Forgiveness (Routledge, 2023).

- Luke Russell, Real Forgiveness (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Myisha Cherry, Failures of Forgiveness: What We Get Wrong and How to Do Better (Princeton University Press, 2023).

- Martha C. Nussbaum, Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Monika Renz, Forgiveness and Reconciliation (Routledge, 2023).

- Matthew Ichihashi Potts, Forgiveness: An Alternative Account (Yale University Press, 2022).

- Christel Fricke, ed., The Ethics of Forgiveness (Routledge, 2011).

- Brandon Warmke, Dana Kay Nelkin & Michael McKenna, eds., Forgiveness and Its Moral Dimensions (Oxford University Press, 2021).

- Jennifer Sandoval, A Psychological Inquiry into the Meaning and Concept of Forgiveness (Routledge, 2017).

- Loren Toussaint, Everett Worthington & David R. Williams, eds., Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health (Springer, 2015).

- Ani Kalayjian & Raymond F. Paloutzian, eds., Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Psychological Pathways to Conflict Transformation and Peace Building (Springer, 2009).

- Lydia Woodyatt, et. al., Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness (Springer, 2017).

- Jeffrey M. Blustein, Forgiveness and Remembrance: Remembering Wrongdoing in Personal and Public Life (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- David Konstan, Before Forgiveness: The Origins of a Moral Idea (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Handbook of Forgiveness (Routledge, 2nd edition, 2019).

- Everett L. Worthington, Jr., A Just Forgiveness: Responsible Healing Without Excusing Injustice (IVP Books, 2009).

- Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Theory and Application (Routledge, 2006).

- Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Forgiving and Reconciling: Bridges to Wholeness and Hope (IVP, 2003).

- Robert D. Enright, Forgiveness Is a Choice: A Step-by-Step Process for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope (American Psychological Association, 2001).

- Robert D. Enright PhD & Dr. Richard P. Fitzgibbons, Forgiveness Therapy: An Empirical Guide for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope (American Psychological Association, 2nd edition, 2014).

- Robert D. Enright, Helping Clients Forgive: An Empirical Guide for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope (American Psychological Association, 2000).

- The Dalai Lama and Victor Chan, The Wisdom of Forgiveness: Intimate Conversations and Journeys (Riverhead, 2004).

- Charles Griswold, Forgiveness: A Philosophical Exploration (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Vlademir Jankélévitch, Forgiveness (University of Chicago Press, 2005).

- Solomon Schimmel, Wounds Not Healed by Time: The Power of Repentance and Forgiveness (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Lewis B. Smedes, Forgive and Forget: Healing the Hurts We Don't Deserve (HarperCollins, 1984).

- Desmond Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (Doubleday, 1999).

- Nathaniel Philbrick, Why Read Moby Dick?(Viking, 2011): “‘The mythic incarnation of America: a country blessed,’ in Philbrick’s words, ‘by God and by free enterprise that nonetheless embraces the barbarity it supposedly supplanted,’ we are a nation, and a species, ever poised on self-destruction.”

- Sidney B. Simon and Suzanne Simon, Forgiveness: How to Make Peace with Your Past and Get on With Your Life (Grand Central Publishing, 1991).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

- The Power of Forgiveness, an Amish response to an atrocity.

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Valjean has stolen from the bishop. The police have apprehended him and brought him to the bishop. The bishop then changes Valjean’s view of the world, and his life, with an exceptional act of forgiveness.

A few moments later he was breakfasting at the very table at which Jean Valjean had sat on the previous evening. As he ate his breakfast, Monseigneur Welcome remarked gayly to his sister, who said nothing, and to Madame Magloire, who was grumbling under her breath, that one really does not need either fork or spoon, even of wood, in order to dip a bit of bread in a cup of milk. "A pretty idea, truly," said Madame Magloire to herself, as she went and came, "to take in a man like that! and to lodge him close to one's self! And how fortunate that he did nothing but steal! Ah, mon Dieu! it makes one shudder to think of it!" As the brother and sister were about to rise from the table, there came a knock at the door. "Come in," said the Bishop. The door opened. A singular and violent group made its appearance on the threshold. Three men were holding a fourth man by the collar. The three men were gendarmes; the other was Jean Valjean. A brigadier of gendarmes, who seemed to be in command of the group, was standing near the door. He entered and advanced to the Bishop, making a military salute. "Monseigneur--" said he. At this word, Jean Valjean, who was dejected and seemed overwhelmed, raised his head with an air of stupefaction. "Monseigneur!" he murmured. "So he is not the curé?" "Silence!" said the gendarme. "He is Monseigneur the Bishop." In the meantime, Monseigneur Bienvenu had advanced as quickly as his great age permitted. "Ah! here you are!" he exclaimed, looking at Jean Valjean. "I am glad to see you. Well, but how is this? I gave you the candlesticks too, which are of silver like the rest, and for which you can certainly get two hundred francs. Why did you not carry them away with your forks and spoons?" Jean Valjean opened his eyes wide, and stared at the venerable Bishop with an expression which no human tongue can render any account of. "Monseigneur," said the brigadier of gendarmes, "so what this man said is true, then? We came across him. He was walking like a man who is running away. We stopped him to look into the matter. He had this silver--" "And he told you," interposed the Bishop with a smile, "that it had been given to him by a kind old fellow of a priest with whom he had passed the night? I see how the matter stands. And you have brought him back here? It is a mistake." "In that case," replied the brigadier, "we can let him go?" "Certainly," replied the Bishop. The gendarmes released Jean Valjean, who recoiled. "Is it true that I am to be released?" he said, in an almost inarticulate voice, and as though he were talking in his sleep. "Yes, thou art released; dost thou not understand?" said one of the gendarmes. "My friend," resumed the Bishop, "before you go, here are your candlesticks. Take them." He stepped to the chimney-piece, took the two silver candlesticks, and brought them to Jean Valjean. The two women looked on without uttering a word, without a gesture, without a look which could disconcert the Bishop. Jean Valjean was trembling in every limb. He took the two candlesticks mechanically, and with a bewildered air. "Now," said the Bishop, "go in peace. By the way, when you return, my friend, it is not necessary to pass through the garden. You can always enter and depart through the street door. It is never fastened with anything but a latch, either by day or by night." Then, turning to the gendarmes:-- "You may retire, gentlemen." The gendarmes retired. Jean Valjean was like a man on the point of fainting. The Bishop drew near to him, and said in a low voice:-- "Do not forget, never forget, that you have promised to use this money in becoming an honest man." Jean Valjean, who had no recollection of ever having promised anything, remained speechless. The Bishop had emphasized the words when he uttered them. He resumed with solemnity:-- "Jean Valjean, my brother, you no longer belong to evil, but to good. It is your soul that I buy from you; I withdraw it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God." [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume I – Fantine; Book Second – The Fall, Chapter XII, “The Bishop Works”.]

The rebels have handed Javert over to Valjean, whom Javert has pursued mercilessly for decades. Perhaps recalling the Bishop’s kindness from years ago, Valjean performs an extraordinary act. Armed with a pistol and all but explicitly instructed to kill Javert, Valjean instead does this:

Jean Valjean thrust the pistol under his arm and fixed on Javert a look which it required no words to interpret: "Javert, it is I." Javert replied: "Take your revenge." Jean Valjean drew from his pocket a knife, and opened it. "A clasp-knife!" exclaimed Javert, "you are right. That suits you better." Jean Valjean cut the martingale which Javert had about his neck, then he cut the cords on his wrists, then, stooping down, he cut the cord on his feet; and, straightening himself up, he said to him: "You are free." Javert was not easily astonished. Still, master of himself though he was, he could not repress a start. He remained open-mouthed and motionless. Jean Valjean continued: "I do not think that I shall escape from this place. But if, by chance, I do, I live, under the name of Fauchelevent, in the Rue de l'Homme Armé, No. 7." Javert snarled like a tiger, which made him half open one corner of his mouth, and he muttered between his teeth: "Have a care." "Go," said Jean Valjean. Javert began again: "Thou saidst Fauchelevent, Rue de l'Homme Armé?" "Number 7." Javert repeated in a low voice:--"Number 7." He buttoned up his coat once more, resumed the military stiffness between his shoulders, made a half turn, folded his arms and, supporting his chin on one of his hands, he set out in the direction of the Halles. Jean Valjean followed him with his eyes: A few minutes later, Javert turned round and shouted to Jean Valjean: "You annoy me. Kill me, rather." Javert himself did not notice that he no longer addressed Jean Valjean as "thou." "Be off with you," said Jean Valjean. Javert retreated slowly. A moment later he turned the corner of the Rue des Prêcheurs. When Javert had disappeared, Jean Valjean fired his pistol in the air. Then he returned to the barricade and said: "It is done." [Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862), Volume V – Jean Valjean; Book First – The War Between Four Walls, Chapter XIX, Jean Valjean Takes His Revenge.]

A sincere apology can remove obstacles to forgiveness. In this scene, Scrooge visits his nephew on the day of Scrooge’s rebirth:

In the afternoon he turned his steps towards his nephew's house. He passed the door a dozen times, before he had the courage to go up and knock. But he made a dash, and did it: "Is your master at home, my dear?" said Scrooge to the girl. Nice girl! Very. "Yes, sir." "Where is he, my love?" said Scrooge. "He's in the dining-room, sir, along with mistress. I'll show you up-stairs, if you please." "Thank'ee. He knows me," said Scrooge, with his hand already on the dining-room lock. "I'll go in here, my dear." He turned it gently, and sidled his face in, round the door. They were looking at the table (which was spread out in great array); for these young housekeepers are always nervous on such points, and like to see that everything is right. "Fred!" said Scrooge. Dear heart alive, how his niece by marriage started! Scrooge had forgotten, for the moment, about her sitting in the corner with the footstool, or he wouldn't have done it, on any account. "Why bless my soul!" cried Fred, "who's that?" "It's I. Your uncle Scrooge. I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?" Let him in! It is a mercy he didn't shake his arm off. He was at home in five minutes. Nothing could be heartier. His niece looked just the same. So did Topper when he came. So did the plump sister when she came. So did every one when they came. Wonderful party, wonderful games, wonderful unanimity, won-der-ful happiness! [Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843), Stave V “The End of It”.]

Other novels:

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick, or The White Whale (1892): a story of a man who could not let it go.

- Miriam Toews, Women Talking: A Novel (Bloombury Publishing, 2019): “Toews skips over the rapes and the apprehension of the rapists, cutting straight to existential questions facing the women in the aftermath. ‘Women Talking’ is a wry, freewheeling novel of ideas that touches on the nature of evil, questions of free will, collective responsibility, cultural determinism and, above all, forgiveness. As Agata Friesen, an unflappable matriarch, puts it: ‘Let’s talk about our sadness after we have nailed down our plan.’”

- Amity Gaige, Sea Wife: A Novel (Knopf, 2020): “. . . Gaige maps two journeys for readers — one into the distant past, leading us to difficult answers to Juliet’s questions, and the other following the family’s ambitious sailing expedition aboard a 44-foot boat.” [Gaige’s novel gives readers plenty to discuss, including ethical dilemmas, complicated family dynamics and the nature of forgiveness.]

- Charlotte Wood, Stone Yard Devotional: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2023), “is the diary of a person with more days behind her than ahead, tired of trying and failing to rescue the planet from man-made destruction, wanting to make her way home. Apocalypse is not so much the plot of the book as its anchor, grounding the novel’s ruminations on forgiveness and regret, on how to live and die, if not virtuously, then as harmlessly as possible.”

- Amie Barrodale, Trip: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2025): a woman dies, having farmed out her autistic son to custodial care. In a life after death, “memories constitute Sandra’s unfinished business, attachments she must move beyond. They’re suffused with her regret that she could have done more to help her son, and her helpless rage at the professionals who suggest that there’s something wrong with him.”

Novels from the dark side:

- Giaime Alonge, The Feeling of Iron: A Novel (Europa Editions, 2025) “follows two Holocaust survivors on a quest for revenge. . . . The novel’s title comes from a conversation between Lichtblau and Baron von Lehndorff, just after the castle is appropriated by the Nazis. The baron, a former fencing champion, agrees to some friendly bouts with his guest, with whom he adamantly disagrees about everything else. ‘You need to feel the blade as if it were an extension of your arm,’ von Lehndorff advises during a break. ‘You don’t need eyes to move your wrist. The French call it le sentiment du fer, a feel for the iron.’ It is a fine metaphor for what happens when war’s costs are internalized and become part of us.”

Poetry

Forgiving:

I was angry with my friend; / I told my wrath, my wrath did end. / I was angry with my foe: / I told it not, my wrath did grow.

And I waterd it in fears, / Night & morning with my tears: / And I sunned it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles. / And it grew both day and night. / Till it bore an apple bright. / And my foe beheld it shine, / And he knew that it was mine.

And into my garden stole, / When the night had veild the pole; / In the morning glad I see; / My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

[William Blake, “A Poison Tree” (1794).]

Other poems:

- Joy Harjo, “I Give You Back”

- Edgar Lee Masters, “Elmer Karr”

- Tony Hoagland, “Lucky”

From the dark side:

- Doireann Ni Ghriofa, A Ghost in the Throat (Biblioasis, 2021): on the Irish poem “Caoineadh Airt Ui Laoghaire” by Eibhlin Dubh Ni Chonaill, about a woman’s grief and obsessive longing for revenge after her husband is murdered.

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

Arnold Schönberg (Schoenberg), Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), Op. 4 (1899, rev. 1943) (approx. 25-30’) (list of recorded performances), is based on a poem by Richard Dehmel, about a young woman who confesses to a man that she bears another man’s child; her companion transforms the night when he accepts and forgives. The man tells her: “Look at this brilliant, moonlit world . . . It is like a cold ocean, but there is a flame within each of us that warms the other and which will transfigure the child and make it mine also.” “The various emotions of the two characters – love, pain, guilt, jealousy, forgiveness, and so on – find their equivalents in Schoenberg's passionate music.” Hollywood Quartet with Dinkin and Reher in 1950, Pierre Boulez's Ensemble InterContemporain in 1984, Juilliard String Quartet with Ma and Trampler in 1991, Smithsonian Chamber Players in 2011, Quatuor Ébène with Tamestit and Altstaedt in 2021, and Hamburg Trio in 2023 have given us top performances. Top performances of the orchestral version (1917) have been conducted by Ormandy in 1934, Stokowski in 1956, Mitropoulos in 1958 with the New York Philharmonic, Mitropoulos in 1958 with the Vienna Philharmonic, Karajan in 1973, Karajan in 1988, Herzog in 2021, and Luisi in 2024.

Leoš Janáček, Jenůfa (1903) (approx. 128-136’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances) “revolves around one of the worst crimes portrayed in any opera, the drowning of a newborn infant in an icy river. It's an act driven by narrowmindedness and cowardice — but also by love. And remarkably, the overall theme of the opera is forgiveness. When the title character's child is murdered by her own stepmother, Jenufa reacts not with calls for vengeance, but with tender absolution — set to some of Janacek's most radiant music.” The composer drew the opera from a play by Gabriela Preissová, entitled “Její pastorkyňa” (Her Stepdaughter) (1890). Performances with video are conducted by Schneider, Bolton, and Pastorkyňa. A top audio-recorded performance is by Söderström, Ochman, Dvorský, Randová, Popp & Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (Mackerras) in 1982.

Quatuor Ébène has released an album called “’round midnight” (2021) (70’), which includes their performance of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, and also two other works on the same theme:

- Henri Dutilleux, Ainsi la Nuit (1976) (approx. 18’); and

- Raphaël Merlin, “Night Bridge” (2017).

The Scottish instrumental and singing group Silly Wizard performed traditional Scottish songs of heartaches, lost loves and home. That does not sound like forgiving, it sounds like holding on. But when you hear them, you understand that the music soothes and allows the letting go to begin. Here are links to their releases, live performances, and a compilation of tracks.

Compositions:

- George Frideric Händel, Joseph & His Brethren, HWV 59 (1743) (approx. 169-177’) (program and libretto) (list of recorded performances) (performances conducted by McGegan, McGegan, and Armaah), and Willem de Fesch, Joseph (1745) (approx. 140’): these two oratorios are based on Chapters 37-45 of Genesis in The Bible, telling the story of how Joseph’s brothers betray him but he is resilient, survives, thrives and welcomes them into his bounty.

- Johann Mattheson, Joseph (1727) (approx. 50’) is another oratorio about the biblical Joseph story, from a contemporary and friend of Händel.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, La Clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus), K. 621 (1791) (approx. 133-148’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances): many have plotted against him but Titus pardons them all. Performances are conducted by Levine, Davis and Pritchard.

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Le Conte du Tsar Saltan (The Tale of Tsar Saltan) (1900) (approx. 140-147’) is a light-hearted treatment of forgiveness, stemming from a longstanding practical joke. Performances are conducted by Nebolsin, and unknown.

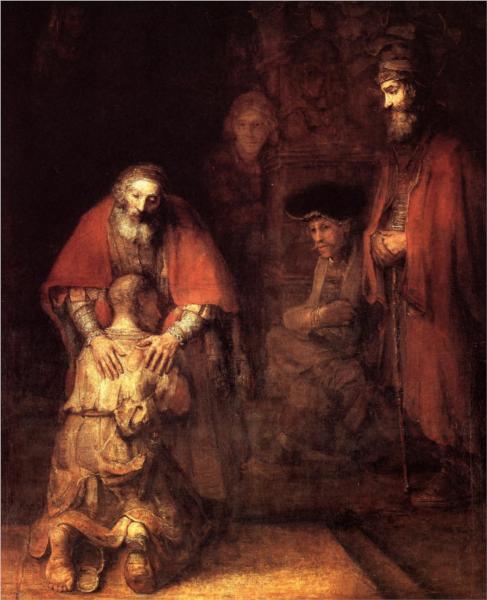

- Sergei Prokofiev, The Prodigal Son (Le Fils prodigue), Op. 46 (1929) (approx. 38’) (recordings): the title suggests that it is a ballet based on the biblical story. However, the “libretto is based less on the biblical account of the parable found in St. Luke than on a passage from Alexander Pushkin’s short story, The Stationmaster (1830), in which the author describes engravings depicting scenes from the parable that hang in a postal station somewhere in Russia: ‘In the first picture, a venerable old man in a night cap and dressing gown was bidding farewell to a restless youth who was hastily receiving his blessing and a bag of money. Another displayed in vivid detail the dissolute conduct of the young man, who was depicted seated at a table surrounded by false friends and shameless women. The last of the series showed his return to his father; the good old man, still in his night cap and dressing gown, ran out to meet him; the prodigal son knelt at his feet.’”

- Prokofiev, Symphony No. 4 in C Major, Op. 11 (1930, rev. 1947) (approx. 39-40’) (recordings): “Prokofiev wrote the score, using music originally written for the ballet Prodigal Son . . .”

Albums:

- Elora Festival Singers, “The Mystery of Christmas” (1998) (67’)

- Eaken Piano Trio, “I’ll Be Home for the Holidays” (1999) (76’)

On the gray side: In these Vivaldi operas, everyone is forgiven at the end – everyone who has survived. The forgiveness theme has a decidedly rough edge.

- Bajazet, RV 703 (1735) (approx. 147-186’) (program and libretto): “The Ottoman sultan Bajazet has been defeated and taken captive by the ruthless Tartar emperor Tamerlano, but defiantly refuses to submit to him. Tamerlano wishes to marry Bajazet’s daughter Asteria, for whom he is prepared to ditch his fiancée Irene, but Asteria, after some confusions, remains loyal to her true love Andronico, one of Tamerlano’s allies. Just as the furious Tamerlano is promising all manner of dire punishments, Bajazet’s suicide brings him to his senses and the original relationships are restored.”

- Orlando finto pazzo, RV 727 (1714) (approx. 203-213’) (libretto): “Argillano rejects Tigrinda, who then drinks her own potion. Grief-stricken, Grifone, too poisons himself. Origille, seeing the corpse of her beloved, vows revenge. Orlando smashes his fetters, releases Brandimarte, and by destroying Ersilla’s castle, breaks all her spells. Grifone, Tigrinda, and all her other victims reawaken and are cured, Tigrinda is united with Argillano, Origille with Grifone, and all ends happily.” Sort of.

- Orlando furioso, RV 728 (1727) (approx. 170-188’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances): “Inside the temple of Hecate, Bradamante disguises herself as a man. Alcina falls in love with her. Orlando, still raving mad about the marriage of Angelica and Medoro, fights with the temple statues, inadvertently destroying Alcina's power. In a deserted island. Alcina tries to attack the sleeping Orlando, but is prevented by Ruggiero and Bradamante. Astolfo returns to arrest Alcina. Orlando regains his reason and forgives Angelica and Medoro.”

- L’Olimpiade, RV 725 (1733) (approx. 153-175’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances): “King Clistene . . . has promised his daughter Aristea . . . to the winner, but she loves, and is loved by, Megacle . . . Into this mix comes Argene . . . who was romantically linked to Licida, who now loves Aristea; but because Licida has no chance of winning the Games he asks his friend Megacle to play, disguised as him. Megacle wins, but Aristea thinks it’s Licida and is downcast since she loves Megacle; Argene tells the king about the switcheroo of identities. Licida is exiled but is later discovered to be the king’s long-lost son. He’s pardoned, he weds Argene, and Aristea and Megacle wed too.”

- Ercole sul Termodonte (Hercules on Thermodon), RV 710 (1723) (approx. 133-144’) (libretto): “The story is based on the ninth of twelve legendary Labors of Hercules. To atone for killing his children in wrath, Hercules must perform twelve labors, the ninth of which is to travel to Thermodon and capture the sword of the Amazon Queen Antiope. (In other versions of the story, the quest was for her magical girdle.) The Amazons were a tribe of female warriors who put all their male children to death. Hercules, accompanied by the heroes Theseus, Telamon and Alceste, attacks the Amazons and captures Martesia, daughter of the queen. The Amazons then capture Theseus and, as soon as Queen Antiope swears to sacrifice him, Hippolyte falls in love with him. In the end, the goddess Diana decrees the marriage of Hippolyte with Theseus, prince of Athens, and of Martesia with Alceste, king of Sparta.”

- Tito Manlio, RV 738 (1719) (approx. 185-188’) (libretto): “Titus Manlius is engaged in war with the people of Latium. Conflicts of love and duty arise, with his daughter Vitellia in love with the Latin commander Geminius, but loved by the Latin Lucius. Manlius, the son of Titus, kills Geminius, disobeying his father, and is condemned to death, in spite of the pleas of his beloved Servilia, sister of Geminius. He rejects the offer of Lucius to free him. There is eventual reconciliation between father and son.

From the dark side:

Richard Strauss, Elektra, Op. 58 (1909) (approx. 108-116’) (libretto) (list of recorded performances): in this opera, the title character destroys herself by refusing to forgive. A performance with video features Marton with Abbado. Top audio-only recorded performances are by:

- Lammers, Milinkovic & Royal Opera House (Kempe) in 1958;

- Borkh, Madeira & Staatskapelle Dresden (Böhm) in 1960;

- Nilsson, Resnick & Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (Solti) in 1966;

- Marton, Lipovšek & Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Sawallisch) in 1990; and

- Polaski, Palmer & WDR Symphony Cologne (Bychkov) in 2004 ***.

Susan Botti, Dido Refuses to Speak (approx. 34’) (which occurs in the Underworld, after she kills herself, after being abandoned – from “Gates of Silence”)

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Kesha, “Praying” (lyrics)

- Laurie Lewis, “Haven of Mercy”

- Nawang Khechog, “Giving and Forgiving”

- Hugo Wolf, “Nun lass uns Frieden schliessen, liebstes Leben” (Let Us Make Peace, Love of My Life), from Italienisches Liederbruch (No. 8) (1892)

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- Ordinary People, a moving film about self-forgiveness

- The Marrying Kind, about the compromises, before and after the fact, necessary in a marriage

- The Scoundrel: about saving grace in the forgiveness of others

- The Well-Digger’s Daughter (Le fille du puisatier): about a man coming to terms with his daughter’s unanticipated pregnancy

From the dark side, revenge:

- Titus: Shakespeare’s exposition on revenge, set in ancient Rome and brilliantly adapted for film

- In the Bedroom, about two people whose lives are torn apart by their son’s murder; the film is “about revenge--not just to atone for a wound, but to prove a point”