The title of this topic comes from Paul Simon’s song “Train in the Distance“, wherein Simon writes “negotiations and love songs are often mistaken for one and the same.” The idealized version of marriage is continual bliss but the truth, in a relationship between sincere parties, is an ongoing series of negotiations and a search for harmony. Negotiation is part of every relationship.

The best human interactions are based on equality and mutual respect. In a relationship of people of unequal power, the more powerful party must accord the less powerful party equality if the interaction is to be ethical. In other words, our commitment is first, not to take advantage of others and second, to support each other and together create a better life than any of the parties could have alone.

Real

True Narratives

- Jeffrey Krivis, Improvisational Negotiation: A Mediator's Stories of Conflict About Love, Money, Anger - and the Strategies That Resolved Them (Jossey-Bass, 2006).

- Fredrik Stanton, Great Negotiations: Agreements That Changed the Modern World (Westholme Publishing, 2010).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Most studies of negotiations emphasize ways to achieve or leverage power and obtain more power.

- Roger Dawson, Secrets of Power Negotiating (Career Press, 2010).

- Roy Lewicki, Bruce Barry and David Sanders, Negotiation (McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2009).

- I. William Zartman and Guy Olivier Faure, eds., Escalation and Negotiation in International Conflicts (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- I. William Zartman, Negotiation and Conflict Management: Essays on Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2008).

Others describe methods for mutually satisfying negotiations in business and diplomacy.

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Andrea K. Schneider and Lela P. Love, Negotiation: Procedures for Problem Solving (Aspen Publishers, 2006).

- Andrea Kupfer Schneider and Christopher Honeyman, The Negotiator's Fieldbook: The Desk Reference for the Experienced Negotiator (American Bar Association, 2006).

- Francisco Aguilar and Mauro Galluccio, Psychological and Political Strategies for Peace Negotiations: A Cognitive Approach (Springer, 2010).

- Raymond Cohen, Negotiating Across Cultures: International Communication In an Interdependent World (United States Institute of Peace, 1997).

- The Journal of Conflict Resolution

Some people are experts in mediating other people's conflicts.

- Joseph P. Stulberg and Lela P. Love, The Middle Voice: Mediating Conflict Successfully (Carolina Academic Press, 2008).

- Carrie J. Menkel-Meadow, Lela Porter Love and Andrea Kupfer Schneider, Mediation: Practice, Policy, and Ethics (Aspen Publishers, 2006).

- Carrie J. Menkel-Meadow, Lela Porter Love, Andrea Kupfer Schneider and Jean R. Sternlight, Dispute Resolution: Beyond the Adversarial Model (Aspen Publishers, 2004).

Consider the negotiations in which people look beyond power to more mutually satisfying and sustainable solutions.

- Betty Carter and Joan K. Peters, Love, Honor & Negotiate: Building Partnerships That Last a Lifetime (Pocket Books, 1996).

- Harriet Lerner, The Dance of Connection: How to Talk to Someone When You're Mad, Hurt, Scared, Frustrated, Insulted, Betrayed, or Desperate (HarperCollins, 2001).

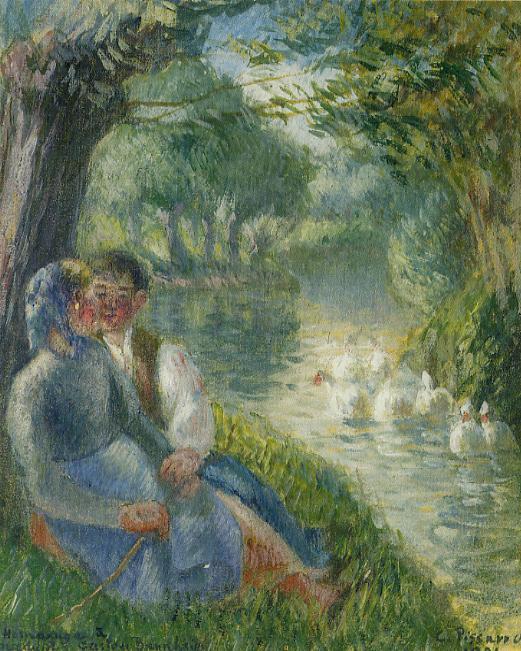

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

The lyrics to Paul Simon’s song, “Train in the Distance”, include the observation: “Negotiations and love songs / Are often mistaken for one and the same”. Or, as they say, can’t live with ‘em, can’t live without ‘em.

With its close interplay between two disparate voices, the violin-piano sonata form naturally conveys a sense of intimacy and interchange. Of necessity, the two voices engage in a back-and-forth musical dialogue, each player in turn taking and ceding the foreground. While this occurs in other chamber forms as well, it is most easily heard here.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s sonatas for violin and piano (list of recordings):

- No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12, No. 1 (1798) (approx. 19-25’)

- No. 2 in A Major, Op. 12, No. 2 (1798) (approx. 16-20’)

- No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 12, No. 3 (1798) (approx. 17-22’)

- No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23 (1801) (approx. 18-26’)

- No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 (“Spring”) (1801) (approx. 25-28’)

- No. 6 in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1 (1802) (approx. 21-23’)

- No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30, No. 2, “Eroica” (1802) (approx. 25-29’)

- No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30, No. 3 (1802) (approx. 20-21’)

- No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47, “Kreutzer” (1803) (approx. 34-46’)

- No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96 (1812) (approx. 28-31’)

Robert Schumann’s three violin sonatas:

- Sonata No. 1 in A minor, Op. 105 (1851) (approx. 17-24’)

- Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 121 (1851) (approx. 27-33’)

- Sonata No. 3 in A minor, WoO 27 (1853) (approx. 21-22’

Other violin sonatas:

- Francis Poulenc, Violin Sonata, FP 119 (1943) (approx. 18-20’)

- Maurice Ravel, Violin Sonata No. 1 in A Minor, M 12 (1897) (approx. 15-21’)

- Camille Saint-Saëns, Violin Sonatas: No. 1 in D minor, Op. 75, R. 123 (1885) (approx. 22-24’); and No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 201, R. 130 (1896) (approx. 23-24’)

- Zygmunt Stojowski, Violin Sonatas: No. 1 in G Major, Op. 13 (1893) (approx. 22-29’); and No. 2 in E minor, Op. 37 (1911) (approx. 27’)

- Heitor Villa-Lobos, Violin Sonata No. 3, W 171 (1920) (approx. 21-22’)

- Amy Beach, Sonata for Violin and Piano in A minor, Op. 34 (1896) (approx. 30-34’)

Many chamber works by Bohuslav Martinů display a character of interaction that evokes this subject of human interaction as negotiation:

- 5 Madrigal Stanzas for Violin & Piano, H 297 (1943) (approx. 11’)

- 5 Short Pieces for Violin and Piano, H 184 (1930) (approx. 11’)

- 7 Arabesques, H 201 (1931) (arr. for violin & piano) (approx. 15’)

- Concerto for Violin & Piano, H 13 (1910) (approx. 27’)

- Czech Rhapsody for Violin and Piano, H 307 (1945) (approx. 10’)

- Elegy for Violin and Piano (1909) (approx. 11’)

- Impromptu for Violin and Piano, H 166 (1927) (approx. 11’)

- Intermezzo, H 261 (1937) (approx. 10’)

- Sonatina in G Major, H 262 (1937) (approx. 10’)

- Duo for Violin and Cello No. 1, H 157 (1927) (approx. 13’)

- Duo for Violin and Cello No. 2, H 371 (1958) (approx. 10’)

- Violin Sonata No. 1, H 182 (1929) (approx. 20’)

- Violin Sonata No. 2, H 208 (1931) (approx. 13’)

- Violin Sonata No. 3, H 303 (1944) (approx. 26-27’)

- Violin Sonata in C Major, H 120 (1919) (approx. 32’)

Mauricio Kagel’s piano trios are dark, often brooding works, evoking troubled interactions between and among the players.

- Piano Trio No. 1 (1985) (approx. 17’)

- Piano Trio No. 2 (2001) (approx. 19’)

- Piano Trio No. 3 (2006) (approx. 28’)

Other compositions:

- Witold Lutosławski, Symphony No. 1 (1947) (approx. 25’): “Ebullient energy characterises all rapid fragments and the intricate metro-rhythmic changes highlight the impetus of the music. The source of these outstanding rhythmic effects which intensify the spontaneity are either added or subtracted rhythmic values and irregular accents.”

- Raga Pahadi Jhinjoti (Pahari Jhinjoti) a Hindustani classical raag. Performances are by Ali Akbar Khan, Nikhil Banerjee and Buddhaditya Mukherjee.

- Arthur Bliss, Conversations for Wind & Strings, F. 16 (1920) (approx. 16’)

- Similarly, though it is written for a single instrument, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 10 in G major, Op. 14, No. 2 (1799) (approx. 15-17’), suggests an interaction between two lovers.

- Gustav Holst, Double Concerto for two violins & small orchestra, Op. 49 (1930) (approx. 15’)

- Heinrich von Herzogenberg, three string quartets: String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 42, No. 1 (1884) (approx. 33-37’); String Quartet No. 2 in D minor, Op. 42, No. 2 (1884) (approx. 36’); String Quartet No. 3 in G Major, Op. 42, No. 3 (1884) (approx. 24’)

- York Bowen, Piano Trio in E Minor, Op. 118 (1945) (approx. 24’); Phantasy Quintet, Op. 93 (1932) (approx. 13-15’)

- Louis Théodore Gouvy, String Quartet No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 68 (1874) (approx. 32’)

- Henryk Górecki, Old Polish Music (Muzyka Staropolska), Op. 24 (1969) (approx. 24-27’): trumpets and strings, with widely divergent perspectives

- Aleksandr Glazunov, String Quartet No. 2 in F Major, Op. 10 (1884) (approx. 30’)

- Glazunov, String Quartet No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 64 (1894) (approx. 33-34’)

- Wilhelm Furtwängler, Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor (1935) (approx. 556’): “A very fine large-scale violin sonata in constant song and imaginative soulful turmoil.”

- Furtwängler, Violin Sonata No. 2 in D Major (1938) (approx. 43-46’): “The Second Sonata bursts with symphonic intent. It is a passionate work deep in the romantic melos and turbulent in the two outer movements (there are three in total).”

- Fred Lehrdahl, Give and Take (2014) (approx. 15’): “The title . . . evokes the responsive and varied interaction of the violin and cello throughout the piece. They are in an intense conversation, sometimes echoing and elaborating one another, other times each going its own way in its own tempo, still other times one breaking off with a change in direction that is soon followed by the other.” [the composer]

Albums:

- Alvin Ayler, “Live on the Riviera” (2005) (57’)

- Derek Bailey & Evan Parker, “Arch Duo” (1999) (70’) “is a rather lengthy continuous improvisation from two of the most well-known and skilled British free improvisers. It's always interesting to hear Evan Parker before he began to perform circular breathing techniques as his primary mode.”

- Arthur Gottschalk, “Art for Two” (2018) (52’)

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Paul Simon, “Train in the Distance” (lyrics)

- Kenny Rogers & Dolly Parton, “Islands in the Stream” (lyrics)

- Avil Lavigne, “Complicated” (lyrics)

- Whitney Houston, “It’s Not Right But It’s Okay” (lyrics)

- Dream, “He Loves U Not” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

- Konstantin Makovsky, Difficult Negotiations (1883)