- They have exiled me now from their society, yet I am content. Mankind only exiles the one whose large spirit rebels against injustice and tyranny. He who does not prefer exile to servility is not free in the true and necessary sense of freedom. [Kahlil Gibran, Spirits Rebellious, “Madame Rose Hanie”, Part II (1908).]

A hero is someone who exhibits courage, bravery, tenacity and imperturbability to good effect. She saves or changes a life, with attendant risk to herself.

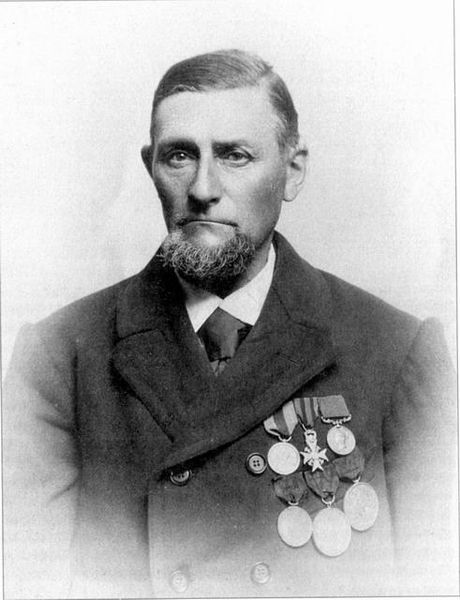

Dorus Rijkers was such a person. He conducted nearly forty rescue operations at sea, more than twenty-five of them before joining the lifeboat service.

Real

True Narratives

Various narratives:

- Dith Pran, compiler, Children of Cambodia’s Killing Fields: Memoirs of Survivors (Yale University Press, 1997): the hero is the compiler of the stories, Dith Pran, who remained in his native Cambodia, at great personal risk, out of a sense of obligation.

- Andrew Gerow Hodges, Jr., and Denise George, Behind Nazi Lines: My Father’s Heroic Quest to Save 149 World War II POWs (Berkley, 2015).

- Eric Lichtblau, Return to the Reich: A Holocaust Refugee’s Secret Mission to Defeat the Nazis (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019): “. . . even as a Gestapo prisoner, Freddy Mayer — beaten bloody, eardrum punctured, teeth missing — wasn’t through. He convinced his captors that rather than killing him, they should surrender to him. Incredibly, they did, along with the entire German garrison, which allowed the advancing American Army to capture the entire Austrian Tyrol without firing a shot.”

- Alex Kernshaw, Avenue of Spies: A True Story of Terror, Espionage, and one American Family’s Heroic Resistance in Nazi-Occupied Paris (Broadway Books, 2016).

- Rebecca Donner, All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days: The True Story of the American Woman at the Heart of the German Resistance to Hitler (Little, Brown and Company, 2021): “Several letters show Mildred trying to present a brave face for her worried family back in the United States. Staying meant risking imprisonment and perhaps death; leaving would have meant abandoning Germany to the Nazis.”

- Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Houghton Mifflin, 1992). This book recounts heroic efforts to expose the crimes of a brutal king.

- Adam Makos, Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship, and Sacrifice (Ballantine Books, 2015): the story of two American wartime aviators, one an African-American who “defended a nation that wouldn’t serve him in a bar.”

- Sahm Venter, ed., The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela (Liveright Publishing, 2018): “The Making of a Moral Hero”

- Marie Brenner, The Desperate Hours: One Hospital’s Fight to Save a City on the Pandemic’s Front Lines (Flatiron Press, 2022): “The book details both medical heroism and corporate cowardice, prescient decisions and howling missteps, all against the backdrop of a swirling and mysterious pandemic that claimed the lives of more than 30,000 residents, not to mention 35 New York-Presbyterian employees.”

- Simon Parkin, The Forbidden Garden: The Botanists of Besieged Leningrad and Their Impossible Choice (Scribner, 2024): “. . . during these years of starvation and suffering, the Plant Institute sheltered some 120 tons of edible seeds. Its scientists hid them, guarded them, refused to distribute them as food even among themselves. . . . They were desperately determined to save a collection gathered as a bulwark against global famine, even at the cost of their own lives or the suffering of the denizens of the city.”

- Alexei Navalny, Patriot: A Memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 2024): “The Russian opposition leader, who died in an Arctic penal colony . . . tells the story of his struggle to wrest his country back from President Vladimir Putin.”

Sports writing, as a narrative about heroes, falls between fiction and non-fiction. These are books about heroism as an ideal, illustrating the point that great things are easier said than done.

- Gay Talese (Michael Rosenwald, ed.), The Silent Season of a Hero: The Sports Writing of Gay Talese (Walker & Company, 2010).

Technical and Analytical Readings

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

No one had yet observed in the gallery of the statues of the kings, carved directly above the arches of the portal, a strange spectator, who had, up to that time, observed everything with such impassiveness, with a neck so strained, a visage so hideous that, in his motley accoutrement of red and violet, he might have been taken for one of those stone monsters through whose mouths the long gutters of the cathedral have discharged their waters for six hundred years. This spectator had missed nothing that had taken place since midday in front of the portal of Notre-Dame. And at the very beginning he had securely fastened to one of the small columns a large knotted rope, one end of which trailed on the flight of steps below. This being done, he began to look on tranquilly, whistling from time to time when a blackbird flitted past. Suddenly, at the moment when the superintendent’s assistants were preparing to execute Charmolue’s phlegmatic order, he threw his leg over the balustrade of the gallery, seized the rope with his feet, his knees and his hands; then he was seen to glide down the façade, as a drop of rain slips down a window-pane, rush to the two executioners with the swiftness of a cat which has fallen from a roof, knock them down with two enormous fists, pick up the gypsy with one hand, as a child would her doll, and dash back into the church with a single bound, lifting the young girl above his head and crying in a formidable voice,— “Sanctuary!” This was done with such rapidity, that had it taken place at night, the whole of it could have been seen in the space of a single flash of lightning. “Sanctuary! Sanctuary!” repeated the crowd; and the clapping of ten thousand hands made Quasimodo’s single eye sparkle with joy and pride. This shock restored the condemned girl to her senses. She raised her eyelids, looked at Quasimodo, then closed them again suddenly, as though terrified by her deliverer. Charmolue was stupefied, as well as the executioners and the entire escort. In fact, within the bounds of Notre-Dame, the condemned girl could not be touched. The cathedral was a place of refuge. All temporal jurisdiction expired upon its threshold. Quasimodo had halted beneath the great portal, his huge feet seemed as solid on the pavement of the church as the heavy Roman pillars. His great, bushy head sat low between his shoulders, like the heads of lions, who also have a mane and no neck. He held the young girl, who was quivering all over, suspended from his horny hands like a white drapery; but he carried her with as much care as though he feared to break her or blight her. One would have said that he felt that she was a delicate, exquisite, precious thing, made for other hands than his. There were moments when he looked as if not daring to touch her, even with his breath. Then, all at once, he would press her forcibly in his arms, against his angular bosom, like his own possession, his treasure, as the mother of that child would have done. His gnome’s eye, fastened upon her, inundated her with tenderness, sadness, and pity, and was suddenly raised filled with lightnings. Then the women laughed and wept, the crowd stamped with enthusiasm, for, at that moment Quasimodo had a beauty of his own. He was handsome; he, that orphan, that foundling, that outcast, he felt himself august and strong, he gazed in the face of that society from which he was banished, and in which he had so powerfully intervened, of that human justice from which he had wrenched its prey, of all those tigers whose jaws were forced to remain empty, of those policemen, those judges, those executioners, of all that force of the king which he, the meanest of creatures, had just broken, with the force of God. And then, it was touching to behold this protection which had fallen from a being so hideous upon a being so unhappy, a creature condemned to death saved by Quasimodo. They were two extremes of natural and social wretchedness, coming into contact and aiding each other. Meanwhile, after several moments of triumph, Quasimodo had plunged abruptly into the church with his burden. The populace, fond of all prowess, sought him with their eyes, beneath the gloomy nave, regretting that he had so speedily disappeared from their acclamations. All at once, he was seen to re-appear at one of the extremities of the gallery of the kings of France; he traversed it, running like a madman, raising his conquest high in his arms and shouting: “Sanctuary!” The crowd broke forth into fresh applause. The gallery passed, he plunged once more into the interior of the church. A moment later, he re-appeared upon the upper platform, with the gypsy still in his arms, still running madly, still crying, “Sanctuary!” and the throng applauded. Finally, he made his appearance for the third time upon the summit of the tower where hung the great bell; from that point he seemed to be showing to the entire city the girl whom he had saved, and his voice of thunder, that voice which was so rarely heard, and which he never heard himself, repeated thrice with frenzy, even to the clouds: “Sanctuary! Sanctuary! Sanctuary!” “Noël! Noël!” shouted the populace in its turn; and that immense acclamation flew to astonish the crowd assembled at the Grève on the other bank, and the recluse who was still waiting with her eyes riveted on the gibbet. [Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, or, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), Volume II, Book Eighth, Chapter VI, “Three Human Hearts Differently Constructed”.]

Novels:

- Marlon James, Black Leopard, Red Wolf: A Novel (Riverhead Books, 2019): “. . . the plot . . . retraces many of the steps that the scholar Joseph Campbell described as stages in the archetypal hero’s journey.”

- Mario Vargas Llosa, The Dream of the Celt: A Novel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2012): a fictional biography of Roger Casement, a “complicated man of conscience, reasserting his credentials as ‘one of the great anticolonial fighters and defenders of human rights and indigenous cultures of his time, and a sacrificed combatant for the emancipation of Ireland.”

- Maurice Carlos Ruffin, The American Daughters: A Novel (One World, 2024): “brings a little-known aspect of the Civil War to vivid life in a tale of enslaved women working as resistance fighters against the Confederacy. Across the South such women risked danger and death to act as saboteurs, spies and scouts for the Union.”

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

The output of contemporary musicians reflects their contemporary understanding of the values they present in their music, including heroism. Today, heroism is more focused on diversity and inclusivity than it was in the past. Heroes now include activists, educators, health care workers, and ordinary people who exhibit dignity in their everyday lives. Today’s hero probably is concerned with social justice and global sustainability. Here are some contemporary albums about being heroic:

- Kendrick Scott Oracle, “We Are the Drum” (2015) (66’) is inspired by the idea that the drum symbolizes unity, resilience, and the heartbeat of humanity.

- Rudresh Mahanthappa, “Hero Trio” (2020) (46’) presents the three artists as superheroes. The title is a spoof on heroism.

- Abdullah Ibrahim, “The Journey” (1977) (44’): the journey is that of free jazz, and the heroes are free-jazz artists.

- Shabaka and the Ancestors, “Wisdom of Elders” (2016) (76’) is a spiritual jazz album in the tradition of Sun Ra, informed by the artists’ familiarity with South African history. The album is “a tribute to those who have played jazz in the townships . . .”

- Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny, “Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories)” (1995) (69’) arose from the musicians’ common background in small towns in Missouri.

- David Bowie, “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” (1972) (39’): “. . . the overall vague notion of a musical alien sex symbol trying to save Earth is certainly appealing.” Here are videos about the album.

- Bruce Springsteen, “Born in the U.S.A.” (1984) (47’) “describes a Vietnam War veteran who returns home to desperate circumstances and few options. Listen only to its surging refrain, though, and you could mistake it for an uncomplicated celebration of patriotism.” Springsteen fan Chris Christie has called the title track “a defiant song about 'I was born in the USA, and I deserve better than what I'm getting.'” The album is about the heroism of veterans, both during their military service and afterwards, fighting back.

- Bob Marley & The Wailers, “Legend” (1984) (72’) is a compilation of Marley’s best tracks. For his activism and his honesty, he is a hero.

- Ben Harper, “Fight for Your Mind” (1994) (69’) is about someone being his own hero.

Like dignity, the concept of heroism has changed over time. Romantic-era compositions about heroism are grounded more in bravery than in courage, courage being more other-centered than bravery. The idea of honor, or dignity, has shifted, now being less about accepting a challenge to a duel at twenty paces, and more about honoring every person in their intrinsic worth. The world having become “smaller” in the sense that people are aware of and directly affected by people from remote parts of the world, loyalty has taken on a more global character. For that reason, most “classical” compositions about heroism present a view of the ideal that does not match 21st-century values. Still, the works illustrate what being heroic meant at the time of composition.

- Richard Strauss, Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life) (1898) (approx. 37-49’): “The work was . . . seen as a flagrant instance of Strauss’s artistic egotism, with its nominal Hero an autobiographical and confessional portrait of the composer himself. Yet, a deeper interpretation reveals the issue of autobiography to be far more complex. We may also hear this composition as a profound response to the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche, and the eternal struggle between the individual and his outer and inner worlds, while seeking solace in domestic love.” The work consists of six movements, described here. Best recordings are by New York Philharmonic Orchestra (Mengelberg) in 1928; NBC Symphony Orchestra (Toscanini) in 1941; Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Reiner) in 1954; London Symphony Orchestra (Ludwig) in 1959; Philadelphia Orchestra (Ormandy) in 1960; Los Angeles Philharmonic (Mehta) in 1968; Concertgebouw Orchestra (Haitink) in 1970; BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Kurt Sanderling) in 1975; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (Solti) in 1978; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (studio) (Karajan) in 1985; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (live) (Karajan) in 1985; Minnesota Orchestra (Oue) in 1997 ***; Staatskapelle Dresden (Sinopoli) in 2001; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (Nelsons) in 2009; Frankfurt Radio Symphony (Orozco-Estrada) in 2014; and NHK Symphony Orchestra (Paavo Järvi) in 2015.

- Ludwig van Beethoven, Egmont, Op. 84 (1810) (approx. 31-37’) (libretto), in which Egmont concludes: “I die for the freedom for which I have lived and fought. Yes, Spain, rally your guardsmen together! Close up your ranks, you do not frighten me.” Beethoven drew his music from Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s play, “Egmont” (1787).

- Edward MacDowell, Piano Sonata No. 2 in G minor (Sonata Eroica), Op. 50 (1895) (approx. 25-31’), “is inspired by the Arthurian legends and contains an elfin and vaguely malevolent second movement that is suggestive of evil magic.”

- Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate, Waktégli olówaŋ (Victory Songs) for Baritone Solo & Orchestra (2012) (approx. 33’) “was composed 'in honor of Lloyd Running Bear, Sr. and all Lakota Indian warriors.'”

- Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-flat Major, Op. 26, “Funeral March on the Death of a Hero” (1801) (19-22’), concludes with an andante movement, the funeral march.

- Philip Glass, Symphony No. 4, “Heroes” (1996) (approx. 46’): “Just as composers of the past have turned to music of their time to fashion new works, the work of Bowie and Eno became an inspiration and point of departure of symphonies of my own.”

- Reinhold Glière, Symphony No. 3 in B minor, "Il'ya Muromets", Op. 42 (1911) (approx. 71-93’), offers a musical account of a legendary Russian hero.

- Alexander Glazunov, Symphony No. 5 in B-flat Major, Op. 55, "Heroic" (1895) (approx. 33-36’), reflects the composer’s “synthesis of nationalistic and cosmopolitan influences . . .”

- Alfredo Casella, Symphony No. 3: Sinfonia, Op. 63, "Elegia Eroica" (Heroic Elegy) (1940) (approx. 42-46’), was commissioned to honor Italian soldiers who were killed during World War I.

- Raga Hamir is a late evening Hindustani classical raag (also Hambir, Hameer or Hamir Kalyan), portrayed as a heroic figure often amid a thunderstorm or battle. Performances are by Vilayat Khan, Ravi Shankar, Amjad Ali Khan, and Veena Sahasrabuddhe.

- Rag Malkauns, “he who wears serpents like garlands”, is a Hindustani classical raag for after midnight. Performances are by Nikhil Banerjee, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Kaushiki Chakraborty, Ajoy Chakraborty, Pran Nath, and Bhimsen Joshi.

- Raga Deshkar is a Hindustani classical raag for early morning. Performances are by Rashid Khan, Ajoy Chakraborty and Shahid Parvez.

- Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate, Waktégli olówaŋ (Victory Songs) for Baritone Solo & Orchestra (2012) (approx. 33’) “was composed 'in honor of Lloyd Running Bear, Sr. and all Lakota Indian warriors.'”

The dark side of heroism: frequently, a hero can effectively meet evil only with evil, or at the very least with behavior that does not presume that opposing forces are behaving with dignity.

- William Schuman, Judith: Choreographic Poem for Orchestra (1949) (approx. 22-23’). “This story of repulsed foreign oppression and aggression combines feminine Jewish heroism, daring, and even revenge. An Assyrian army under General Holofernes has besieged the Israelites and cut off their water supply. Judith, a deeply religious widow, determines to free her people by using the only weapon available to her, her beauty and feminine charms, and she beseeches God to allow the enemy to be smitten by her ruse—through 'the deceit of my lips.'”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Mariah Carey, “Hero” (lyrics)

- Laura Daigle, “Rescue” (lyrics)

- Tina Arena, “Unsung Hero” (lyrics)

- Sérgio Assad, Clarice Assad & Third Coast Percussion, “The Hero”

Visual Arts

Film and Stage

- The Killing Fields, about atrocities under the Khmer Rouge and an heroic reporter who elects to stay in his native Cambodia

- Army of Shadows (L’armée des ombres), about members of the French resistance against Nazi Germany

- Hail the Conquering Hero, a lampoon on heroism

- Hero, a martial arts film from China that illustrates a common conception of heroism