- Equality lies only in human moral dignity. . . . Let there be brothers first, then there will be brotherhood, and only then will there be a fair sharing of goods among brothers. [Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (), Part II, Book VI, Chapter III, “Conversations and Exhorations of Father Zossima”.]

A commitment to universal human worth and dignity necessarily implies a commitment to equality. People do not agree what the nature and extent of that equality should be.

At least, it must include equal opportunity. Most people in the developed world probably would agree with that statement but in fact we do not practice it. Millions of children are born into poverty every year. Those in impoverished lands have virtually no chance to survive, let alone prosper and thrive as we understand those words in the United States.

I am no radical egalitarian. I believe that people should have the opportunity to improve their circumstances by hard work. If talent gives some people advantages over others, those are not advantages I would wish to eradicate because it is impossible to separate talent completely from effort, and I wish to encourage people to do their best.

Demonstrably, the most prosperous countries are mixed economies with as many capitalist features as are consistent with sustainable prosperity. In the economic war between capitalism and communism, capitalism has won, decisively. But that does not mean that all socialist features of political economy must be eliminated. On the contrary, in no nation in the developed world does a pure capitalist economy exist. It never has and it never will, for the simple reason that capitalism, with its foundations in human greed, tends to excess if unchecked. For that reason, state intervention in and regulation of the economy will always be necessary in technologically advanced economies with complex systems of industry, finance and information exchange. The only way this will change is if technology advances to such an extent that it allows virtually economic factors to be controlled individually or locally, as was the case when people grew their own crops and purchased almost no consumer goods. People may complain that government only makes the problem worse but in point of fact, the main reason this is true in quasi-democratic nations like the United States is that most people do not pay attention to or understand the economic forces behind their politics.

Income inequality is a growing concern, again, throughout the developed world. Excessive income inequality threatens social stability and, eventually, prosperity itself. Wealth is and always has conveyed power. If a few people have a certain relative amount of wealth, they also have too much power. That power allows them to structure the terms of economic exchange, in other words, to rig the game. There simply is no getting around this fact, which history demonstrates time and time again – the robber baron era (Gided Age) and the Roaring Twenties in the United States alone – and yet the American people consistently have failed to prevent excessive accumulations of wealth, and are doing it again.

Our technology and the state of our knowledge have advanced to such an extent that a near Utopia is within our grasp, if only we could see our way clear to it. We must understand that our place in society is just that: it is a place at the table. Dinner will not be pleasant if some have no recourse but to scramble for the crumbs under the table. At the same time, the table is only so big: we must make responsible choices in our consumption of resources, including our reproductive choices. If people ever figure this out, the good life may yet be attained and sustained.

Real

True Narratives

Histories:

- Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Temple University Press, 2010).

- Daniel Picketty, A Brief History of Equality (Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2022): “Much of the current discussion of inequality focuses on the period since 1980, when the benefits of growth began to go much more narrowly to the rich than they had before. Although Piketty hardly disputes this, he announces here that he has come to tell an optimistic story, of the world’s astounding progress toward equality. He does this by creating a much wider temporal frame, from 1780 to 2020, and by focusing on politics and measures of well-being as well as economics.”

Movements promoting radical egalitarianism:

- Daniel Gavron, The Kibbutz: Awakening from Utopia (Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2000).

- Henry Near, The Kibbutz Movement, volume 1: Origins and Growth 1909-1939 (The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1992).

- Henry Near, The Kibbutz Movement, volume 2: Crisis and Achievement 1939-1995 (The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2008).

- Rupert Fike, ed., Voices from the Farm: Adventures in Community Living (Book Publishing Company, 1998).

- Diana Leaf Christian, Creating a Life Together: Practical Tools to Grow Ecovillages and Intentional Communities (New Society Publishers, 2003).

- Diana Leafe Christian, Finding Community: How to Join an Ecovillage or Intentional Community (New Society Publishers, 2007).

- Thomas Healy, Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia (Metropolotan, 2021): “The story of Floyd McKissick’s dream, struggle and, ultimately, failure to build an American city on behalf of Black citizens is one of the greatest least-told stories in American history. In ‘Soul City,’ Thomas Healy chronicles this tragically quixotic enterprise by McKissick, a civil rights activist turned capitalist, who attempted, beginning in 1969, to build ‘Soul City,’ a Black-run city on a former slave plantation in rural North Carolina, close to Southern Klan country.”

From the dark side:

- Phil Klay, Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless Invisible War (Penguin Press 2022): “America’s Wars Are Fought by Relatively Few People.”

Technical and Analytical Readings

- Ronald Dworkin, Sovereign Virtue: The Theory and Practice of Equality (Harvard University Press, 2000).

- G.A. Cohen, Rescuing Justice and Equality (Harvard University Press, 2008).

- Bruce Feltham, ed., Justice, Equality and Constructivism: Essays on G.A. Cohen's Rescuing Justice and Equality (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

- Kate Pickard and Richard Wilkinson, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (Allen Lane, 2009).

- Richard Wilkinson, The Impact of Inequality: How to Make Sick Societies Healthier (New Press, 2005).

- Richard Wilkinson, Unhealthy Societies: The Afflications of Inequality (Routledge, 1996).

- Richard Wilkinson, Mind the Gap: Hierarchies, Health and Human Evolution (Yale University Press, 2001).

- Ichiro Kawachi and Bruce P. Kennedy, The Health of Nations: Why Income Inequality Is Harmful to Your Health (New Press, 2002).

- Louis P. Pojman and Robert Westmoreland, Equality: Selected Readings (Oxford University Press, 1996).

Photographs

Documentary and Educational Films

Imaginary

Fictional Narratives

Struggles for equality:

- George Orwell, Animal Farm (1945): an iconic tale of how all animals are equal but some are more equal than others.

- Karen Tei Yamashita, I Hotel (Coffee House Press, 2010), ten stories drawn from San Francisco's Asian communities in the 1960s and 70s.

Poetry

Music: Composers, artists, and major works

A piano trio consists of three usually equal voices: piano, violin and cello. Listen to the interplay between them in Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Trios (top recorded performances include those by Beaux Arts Trio in 1964 and 1979, Zukerman-Du Pré-Barenboim Trio in 1970, Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio in 1970, Borodin Trio in 1987, Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio in 2007 [vol. 1; Vol. 2], Van Baerle Trio in 2020, Sitkovetsky Trio [vol. 1 in 2020; Vol. 2 in 2023], and Weiss Kaplan Stumpf Trio in 2023):

- Piano Trio No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 1, No. 1 (1795) (approx. 30-34’)

- Piano Trio No. 2 in G Major, Op. 1, No. 2 (1795) (approx. 34-38’)

- Piano Trio No. 3 in C minor, Op. 1, No. 3 (1795) (approx. 28-33’)

- Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 11, “Gassenhauer” (1797) (approx. 17-23’) is also a clarinet trio

- Piano Trio No. 5 in D Major, Op. 70, No. 1, "Ghost" (1808) (approx. 22-29’)

- Piano Trio No. 6 in E flat Major, Op. 70, No. 2 (1811) (approx. 29-30’)

- Piano Trio No. 7 in B flat Major, Op. 97, "Archduke" (1811) (approx. 36-45’). Though Beethoven probably did not intend to express equality in writing music for the Archduke, that theme comes through anyway. On the other hand, Beethoven seems to have been fond of, and surely was devoted to, Archduke Rudolph, who was a student of democratic and labor movements. So perhaps there was more intent toward this theme than the work's title suggests.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Triple Concerto for Piano, Violin, Cello and Orchestra in C major, Op. 56 (1803) (approx. 35’): the piano trio was popular in Beethoven’s time but combining it with an orchestra was a challenge. “The problems are vexing: balancing the three distinctly different timbres of the solo instruments with the orchestral body; allotting the themes equitably to each soloist and the orchestra; creating materials terse enough that they do not become unmanageable, yet flexible enough to do duty for all involved. In the matter of equality among the soloists, Beethoven, accurately perceiving that the cello could get lost in the sonic shuffle, overcompensated by giving the low string instrument inordinate prominence by writing in its top register and by having it introduce most of the thematic material.” “. . . this work was written with an amateur pianist in mind: the relatively simple piano part was designed for Beethoven's patron, the Archduke Rudolf; nevertheless, professional musicians are required for the brutal cello part and the less difficult—but still quite challenging—violin part”. “With this music, Beethoven achieved a genre-bending feat which was virtually unprecedented at the time, and has not been attempted by any significant composer since.” Top performances are by Richter, Oistrakh & Rostropovich (Karajan) in 1969; Badura-Skoda, Maier & Bylsma (Collegium Aureum) in 1974; Zeltser, Mutter & Ma (Karajan) in 1979; Bronfman, Shaham & Mørk (Zinman) in 2005; Argerich, Capuçon & Maisky (Rabinovitch-Barakovsky) in 2007; Trio Poseidon (Neeme Järvi) in 2010; Melnikov, Faust & Queyras (Heras-Casado) in 2017; and Barenboim, Mutter & Ma (Barenboim) in 2020.

Carl Maria von Weber, Grand Duo Concertant, Op. 48, J. 204 (1816) (approx. 15-22’): “. . . the Grand Duo presents an equal juxtaposition of two virtuoso solo parts, one on the clarinet, the other on the piano. There is never any question in the listener's mind that this piece is a Duo in the true sense of the word.” Best recordings are by Johnson & Back in 1990, Collins & Lane in 2011, Manasse & Nakamatsu in 2014, Ottensamer & Wang in 2019, and McGill & Chien in 2021.

C.P.E. Bach, Trio Sonatas

- Ensemble of the Classical Era album (56’)

- Trio Cristofori album: Trio Sonatas from WQ 90, 90 and 91 (62’)

- Le Nouveau Quatuor album, Trio Sonatas, WQ 143-147 (66’)

Other piano trios:

- Louis Théodore Gouvy, Piano Trio No. 2 in A minor, Op. 18 (1856) (approx. 29’); Piano Trio No. 3 in B-flat Major, Op. 19 (1856) (approx. 30’); Piano Trio No. 4 in F Major, Op. 22 (1858) (approx. 30’)

- Albéric Magnard, Piano Trio in F Minor, Op 18 (1904) (approx. 35-36’)

- Amy Beach, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 150 (1938) (approx. 16-18’)

- Dietrich Buxtehude, 7 Trio Sonatas, Op. 1, Bux 252-258 (c. 1694) (approx. 58-60’), and 7 Trio Sonatas, Op. 2, Bux 259-265 (c. 1696) (approx. 67’)

Albums:

- Josh White, “Free and Equal Blues”, a compilation (1998) (74’): “Recorded at the height of his career by Moses Asch in the 1940s, he performs these 26 blues, gospel, popular, and hard-hitting topical songs solo or accompanied by such contemporaries as Lead Belly, Mary Lou Williams, and the Almanac Singers.”

- Akiko Tsuruga, Jeff Hamilton & Graham Dechter, “Equal Time” (2019) (47’): “. . . none of them are trying to reinvent the wheel. Theirs is a straight-up, hard-swinging organ trio in the classic tradition.”

Music: songs and other short pieces

- Rhiannon Giddons, “Freedom Highway” (lyrics)

- Credence Clearwater Revival, “Fortunate Son” (lyrics)

- John Mellencamp, “Small Town” (lyrics)

Visual Arts

Shadow side in art (inequality):

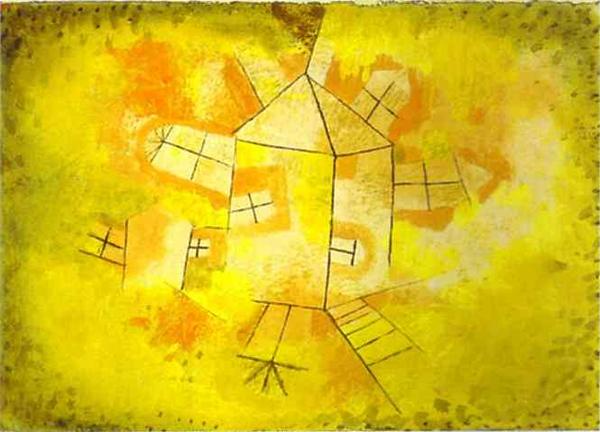

- Wassily Kandinsky, Unequal (1932)

- Pavel Filonov, The Workers (1915-16)

- Jan Vermeer, The Milkmaid (ca. 1660)